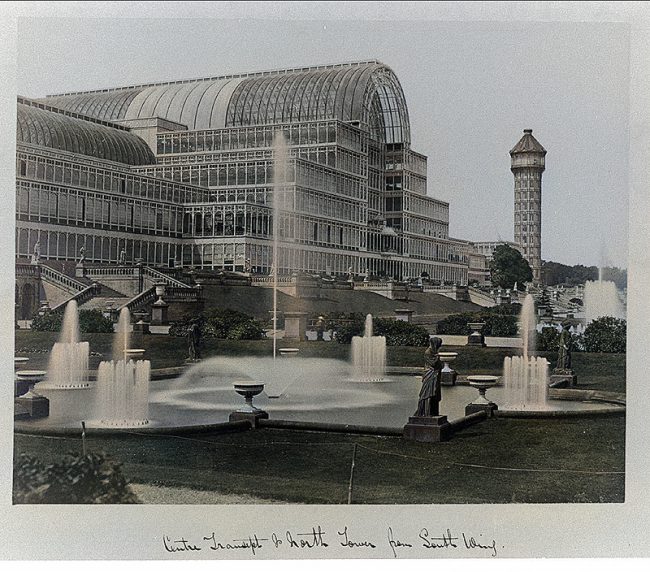

The Crystal Palace at the Great Exhibition 1851

On May, 1st, 1851, Queen Victoria opened the Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, which was the first in a series of World’s Fair exhibitions of culture and industry. A special building, nicknamed The Crystal Palace, a gigantic cast-iron and plate-glass building, was built to house the show on its 92,000 square meters of exhibition space to display examples of the latest technology developed in the Industrial Revolution.

If you took an omnibus along London’s Knightsbridge in the summer of 1851, you would see an astonishing sight. Glittering among the trees was a palace made of glass, like something out of the Arabian Nights. It was as tall as the trees, indeed taller, because the building arched over two of them already growing there, as if, like giant plants in a glasshouse, they had been transplanted with no disturbance to their roots. A shower of rain washed the dust from the glass, and made it glitter all the more. Nothing like this had been seen in London, ever. [1]

A Modern Miracle

This ‘modern miracle’ was the so-called Crystal Palace, home to the Great Exhibition. It was an idea dreamt up by Queen Victoria‘s husband, Prince Albert, to display the wonders of industry and manufacturing from around the modern world.[6] And also it was arguably a response to the highly successful French Industrial Exposition of 1844. Britain was at peace and experiencing a manufacturing boom. This was the time to show off, on the international stage. Although the Great Exhibition was a platform on which countries from around the world could display their achievements, Great Britain sought to prove its own superiority.

“ It is a wonderful place – vast, strange, new and impossible to describe. Its grandeur does not consist in one thing, but in the unique assemblage of all things. Whatever human industry has created, you find there… ” — Charlotte Bronte, in a letter to a friend [3]

Paxton and Brunel

At the exhibit were some 100,000 objects, displayed along more than ten miles, by over 15,000 contributors. Britain, as host, occupied half the display space inside, with exhibits from the home country and the Empire. And the Great Exhibition was staged within the Crystal Palace, designed by Joseph Paxton with support from structural engineer Charles Fox, the committee overseeing its construction including Isambard Kingdom Brunel,[5,7] and went from its organisation to the grand opening in just nine months with 2,000 men working on construction site.

Architectural Adventures

The building was architecturally adventurous, drawing on Paxton’s experience designing greenhouses. It took the form of a massive glass house, 564 metres long by 138 metres wide and was constructed from cast iron-frame components and glass. From the interior, the building’s large size was emphasized with trees and statues; this served, not only to add beauty to the spectacle, but also to demonstrate man’s triumph over nature [2]. The Crystal Palace itself was an enormous success, and also the Great Exhibition. The building was later moved and re-erected in an enlarged form at Sydenham in south London, an area that was renamed Crystal Palace. Unfortunately, it was destroyed by fire in 1936.

Queen Victoria opens the Great Exhibition in The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, in 1851

The Exhibition

Numbering 13,000 in total, the exhibits included a Jacquard loom, an envelope machine, kitchen appliances, steel-making displays and a reaping machine that was sent from the United States. Also the Koh-i-Noor, the world’s biggest known diamond at the time was on display, Frederick Bakewell demonstrated a precursor to today’s fax machine, and firearms manufacturer Samuel Colt demonstrated his prototype for the 1851 Colt Navy. Queen Victoria herself opened the Exhibition on 1st May, on schedule and became a frequent visitor. By the time the Exhibition closed, on 11th October, more that six million people – equivalent to a third of the entire population of Britain at the time – had visited. Instead of initially predicted loss, the Exhibition made a profit of £186,000, most of which was used to create the South Kensington museums.

The Victorians: Time and Space – Professor Richard J. Evans, Gresham College, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Great Exhibition, at The British Library website

- [2] Kishlansky, Mark, Patrick Geary and Patricia O’Brien. Civilization in the West. 7th Edition. Vol. C. New York: Pearson Education, Inc., 2008.

- [3] Charlotte Bronte’s account of a visit to the Great Exhibition mytimemachine.co.uk

- [4] A Virtual Tour at the Great Exhibition 1851, at Stanford University

- [5] Designers Should Think Big – Isambard Kingdom Brunel, SciHi Blog

- [6] Victoria and Albert – a Royal Wedding, SciHi Blog

- [7] Joseph Paxton – from Gardens to Architecture, SciHi Blog

- [8] The Great Exhibition at Wikidata

- [9] “Memorials of the Great Exhibition” (cartoon) Cartoon series from Punch magazine

- [10] air Enough: The London Great Exhibition, 1851 – YouTube, documentary

- [11] The Victorians: Time and Space – Professor Richard J. Evans, Gresham College, 2011, Gresham College @ youtube

- [12] The Great Exhibition: “Wot is To Be” (1850) – booklet, 20pp, at Internet Archive

- [13] Map with Sites of the Great Exhibition of 1851, via Wikidata

A very nice picture of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham Hill, some time after 1856. Those magnificent water towers, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, were only commissioned in 1856 and were not a feature of the original Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, that hosted the Great Exhibition. The two matching water towers each had wrought iron tanks of 290,000 gallons and were interconnected, to maintain a common head of water. The tanks were supported by 12 pairs of 12″ diameter cast iron columns, braced at nine intermediate levels.

Ferrers

British Water Tower Appreciation Society

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #38 | Whewell's Ghost