Frederick II (1194 – 1250)

On December 26, 1194, Frederick II, one of the most powerful Holy Roman Emperors of the Middle Ages and head of the House of Hohenstaufen was born. Speaking six languages (Latin, Sicilian, German, French, Greek and Arabic), Frederick was an avid patron of science and the art, called by a contemporary chronicler stupor mundi (“the wonder of the world”).

“But our intention in this book on falconry is to show what is as it is, and to present it as a reliable art; for hitherto there has been a lack of both science and art in this.”

– Frederick II, in De arte venandi cum avibus. (1258-1266)

Becoming Emperor

Frederick was born in the central Italian town of Jesi in the Marche of Ancona. He was descended from the noble family that later, from the 15th century, was called “Staufer”. In 1196, the only two year old Frederick was crowned King in 1198 after his father Henri VI passed away. His mother Constance established herself as regent and dissolved the ties between Germany and the Empire in his name. His mother passed away very soon as well and he was brought to Palermo, where he is thought to have lived like a street youth. However, his guardian was Pope Innocent III until he was declared of age in 1208 and Frederick was able to marry the 25 year old widow Constance, the daughter of the king of Aragon. Otto of Brunswick was crowned Holy Roman Emperor one year after, but he invaded Italy and sided the Pope against him. However, Frederick was elected as German King and was crowned in 1212 and again a few years later after the passing of Pope Innocent III as Holy Roman Emperor in Rome by Honorius III.

Securing his Empire

In the empire north of the Alps, he was able to assert himself against Otto IV and end the dispute over the throne with the Guelphs that had been going on since 1198. Frederick made numerous concessions to the princes north of the Alps through the Statutum in favorem principum (“Statute in favor of the Princes“) and the Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis (“Alliance with the Princes of the Church“). In the Southern Kingdom, on the other hand, under his rule the central royal power was strengthened by territorial administration and legislation. In 1224 he founded the University of Naples for this purpose. In 1231, with the Constitutions of Melfi, the first secular legal codification of the Middle Ages was issued. With Frederick the Arab settlement of Sicily ended, the integration of the island into the Western and Western cultural area was completed.

Excommunication and Crusade

Frederick II lived in Germany for some years, which was quite unusual for Holy Roman emperors. He helped Philip II of France and brought an end to the War of Succession in Champagne. Frederick repeatedly postponed a crusade he had promised in 1215 due to the reorganization of his kingdom of Sicily, which is why Pope Gregory IX excommunicated him in 1227. Although Frederick was thus excluded from the community of Christendom, he regained the most important pilgrimage sites without a fight during his crusade in 1228/29. In 1230, a temporary settlement with the pope was reached, resulting in the lifting of the excommunication.

Further Conflicts

In northern Italy, Frederick II was unable to perform the traditional ruler’s duties of peacekeeping and law enforcement vis-à-vis the emerging communes. In a society in which honor determined social rank, violations of honor and the resulting compulsion to succeed sparked a crisis of rule that Frederick could no longer manage. The disputes with the communes were closely related to the conflict with the papacy, which broke out again in 1239. At the Council of Lyon in 1245, Emperor Frederick was declared deposed. The power struggle between secular and ecclesiastical leaders was waged on a hitherto unknown scale as a battle of the chanceries. Frederick’s conflict with Popes Gregory IX (1227-1241) and Innocent IV (1243-1254) also prevented joint action against the impending Mongol threat. In general, on top of all this, an increasingly end-time mood spread, while excommunication increasingly dissolved the ties of his rule, which were based on personal loyalty. In the Roman-German Empire, the counter-kings Henry Raspe and William of Holland were elected under Frederick II. In Sicily, there were numerous conspiracies and assassination attempts.

Stupor Mundi – The Wonder of the World

Frederick II, who was called “wonder of the world” often astonished his contemporaries with his unorthodoxy on the one hand and his stubbornness on the other. In concerns of religion, he was known to be a skeptic but remained substantially linked to traditional Christianism. However, his skepticism was very unusual and was seen as highly scandalous. Also his papal enemies used this against him as much as they could. During many occasions, Frederick shocked his contemporaries. For example, he chose not to exterminate the Arab-speaking population of Western Sicily, but enlisted them in his army and even as his personal bodyguards, since they had the advantage of immunity from papal excommunication.

King Konradin, the grandson of Frederick II, lets a falcon soar while hunting with his friend Frederick, Margrave of Baden. Codex Manesse, Heidelberg University Library, Codex Pal. Germ. 848, fol. 7r.

The Thirst for Knowledge and Science

Frederick was not only known for his tolerance, but also for his never ending thirst for knowledge and science. It is said that he never believed what could not be explained by reason and the laws he passed have until this day a quite modern character like the prohibition on physicians acting as their own pharmacists. The court was not only a political but also a cultural focal point. Christian, Muslim and Jewish scholars gathered at Frederick’s court. For these reasons, his court has been called a “hub of cultural transfer” in medieval studies. The most important scholarly advisor and translator for Arabic philosophical texts at the court was the Scot Michael Scotus. His Liber introductorius (“Book of Introduction“) is one of the most important works produced at Frederick’s court.

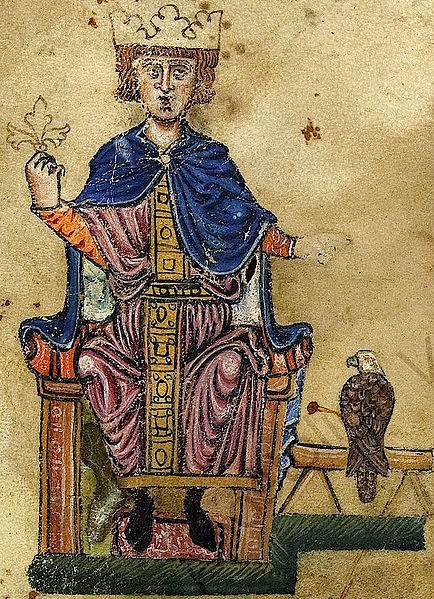

The Art of Hunting with Birds

His favorite pastime was falconry. Probably no other medieval ruler was as enthusiastic about hunting with falcons as Frederick II. At times, up to 50 falconers were in Frederick’s service. However, hunting with trained falcons or hawks was not only a courtly status symbol or a mere pastime, but a science for Frederick. He had the literature on ornithology brought in for this purpose. He had the Arabic hunting literature translated into Latin. The emperor attracted numerous Muslim falconers from Egypt and Arabia to his court. Inspired by his contact with Saracens, Frederick introduced the falconry hood into Western falconry and developed it further. Another innovation lay in the use of cheetahs for muzzle hunting. Under Frederick II, didactic hunting literature reached a peak. In the last decade of his life, the emperor wrote his book De arte venandi cum avibus (“On the Art of Hunting with Birds“). The falconry book describes various approaches to catching and taming falcons. It also describes experiments that were intended to clarify scientific questions. The eyes of a hawk were sewn shut to find out whether these birds of prey perceive meat with their sense of smell or visually. Another experiment was designed to clarify whether ostrich eggs can be hatched by the power of the sun. Over one hundred species of birds are described, some for the first time. The work is an extremely important source for zoology in the 13th century.

“Scientific” Experiments

Historians believe that Frederick also used to perform several experiments on humans like shutting a prisoner up in a cask to see if the soul could be observed escaping though a hole in the cask when the prisoner died. Also he is supposed to have imprisoned children without any contact to see if they would develop a natural language. Frederick II sent many letters to scientists all over the world to seek for answers on the stars as well as mathematics and physics. Frederick’s interest in medicine and the natural sciences was also reflected in reality. The emperor enacted laws against air and water pollution, as well as licensing regulations for physicians and pharmacists.

Death and Legacy

In December 1250, Frederick II died unexpectedly, perhaps of typhoid fever, paratyphoid fever, or blood poisoning. His last hours are described differently by historians. Historians hostile to him drew a picture that corresponded to the ideas of a typical heretic death: he is said to have been poisoned or suffocated, or to have met an agonizing death after severe diarrhea and foaming at the mouth. His corpse is said to have smelled so badly that it could not be transferred to Palermo. This was intended to make it clear that this was a godless person, just as it was taken for granted, according to medieval ideas, that the corpse of a saintly person would smell pleasant. According to other reports, the emperor repented of his sins; thereupon Archbishop Berard of Palermo gave him absolution before he died dressed as a simple Cistercian. With the death of the last Hohenstaufen emperor, historians let the late Middle Ages begin. Papal propaganda demonized Frederick as a persecutor of the church and a heretic, an atheist, the Antichrist, or the Beast of the Apocalypse of John. Among his followers, on the other hand, Frederick was considered the “wonder of the world” (stupor mundi) or “greatest among the princes of the earth” (principum mundi maximus).

Codex of Medicine of Frederick II – Facsimile Editions and Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor (2004) [c. 1250]. The art of falconry: Being the De arte venandi cum avibus of Frederick II of Hohenstaufen. Translated and edited by Casey A. Wood & F. Marjorie Fyfe. Stanford

- [2]“Frederick II., Roman Emperor“. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- [3]“Frederick II. King of Sicily from 1197, and Holy Roman Emperor from 1215 to 1250“. New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- [4] “Frederick II“. Collier’s New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- [5] Psalter of Frederick II from around 1235–1237

- [6] Works by and about Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor in the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (German Digital Library)

- [7] “Fridericus II Imperator”. Repertorium “Historical Sources of the German Middle Ages” (Geschichtsquellen des deutschen Mittelalters).

- [8] Frederick II at Wikidata

- [9] Codex of Medicine of Frederick II – Facsimile Editions and Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts, Facsimile Finder – Manuscript Facsimile Editions

[10] Timeline of Holy Roman Emperors, via Wikidata