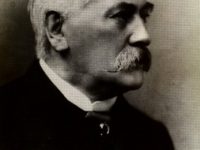

François Lenormant, (1837 – 1883)

On January 17, 1837, French assyriologist and archaeologist François Lenormant was born. Lenormant recognized, from cuneiform inscriptions, a language now known as Akkadian that proved valuable to the understanding of Mesopotamian civilization 3,000 years before the Christian era.

François Lenormant – Youth and Education

François Lenormant was born in Paris, France, to his father Charles Lenormant, who, distinguished as an archaeologist, numismatist and Egyptologist, was anxious that his son should follow in his steps. He made him begin Greek at the age of six, and the child responded so well to this precocious scheme of instruction, that when he was only fourteen an essay of his, “Lettre â M. Hase sur des tablettes grecques trouvées â Memphis”, on the Greek tablets found at Memphis, appeared in the Revue Archéologique. In 1856 he won the numismatic prize of the “Académie des Inscriptions with an essay entitled Classification des monnaies des Lagides”. While pursuing his classical studies, he attended the lectures of the faculty of law and in 1857 received his degree as licentiate.

Archaeological Research in Eleusis

In 1858 he visited Italy and in 1859 accompanied his father on a journey of exploration to Greece, during which Charles succumbed to fever at Athens. Lenormant returned to Greece three times during the next six years, supervising excavations at Eleusis and gave up all the time he could spare from his official work to archaeological research. He conducted important excavations at Eleusis and as a result published several essays, notably: “Recherches archéologiques â Eleusis” (Paris, 1862). While thus engaged he heard of the massacre of Christians by the Druses and immediately ceasing his researches sailed for Syria to go to the rescue of the victims of Moslem fanaticism. When the French expedition reached Syria, he felt free to return to Eleusis.[1]

Academic Career

In 1862 he became sub-librarian of the Institut de France. In 1865 and 1866 he travelled again through the East, and shortly after this, he summarized his studies in a popular Manuel d’histoire ancienne de l’Orient jusqu’aux guerres Médiques (Paris 1868). In 1869 he visited Egypt and familiarized himself with Egyptian antiquities; he published numerous essays on the cuneiform texts and on the language spoken in Babylon and Nineveh.[1] These labors were rudely interrupted by the Franco-Prussian War, when Lenormant served with the army and was wounded in the Siege of Paris. In 1874 he was appointed professor of archaeology at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, and in the following year he collaborated with the Baron Jean de Witte in founding the Gazette archéologique for the publication of unknown monuments and miscellaneous archæological studies.

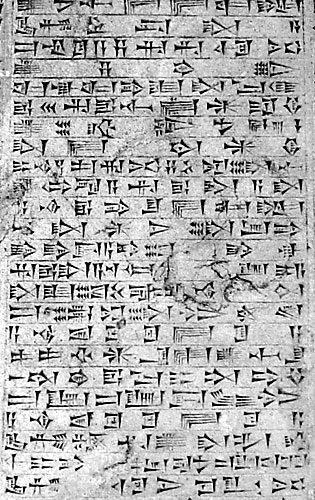

Image of an unidentified cuneiform tablet with an unknown Akkadian inscription in the British Museum, London.

Assyrian Studies

As early as 1867 Lenormant had turned his attention to Assyrian studies; he was among the first to recognise in the cuneiform inscriptions the existence of a non-Semitic language he named Akkadian (today it is known as Sumerian). The earliest attested Semitic language, it used the cuneiform writing system, which was originally used to write the unrelated Ancient Sumerian, a language isolate. The language was named after the city of Akkad, a major centre of Mesopotamian civilization during the Akkadian Empire (ca. 2334–2154 BC), but the language itself precedes the founding of Akkad by many centuries. The Akkadian Empire, established by Sargon of Akkad, introduced the Akkadian language (the “language of Akkad”) as a written language, adapting Sumerian cuneiform orthography for the purpose.

Lenormant’s knowledge was of encyclopaedic extent, ranging over an immense number of subjects, and at the same time thorough, though somewhat lacking perhaps in the strict accuracy of the modern school. Most of his varied studies were directed towards tracing the origins of the two great civilizations of the ancient world, which were to be sought in Mesopotamia and on the shores of the Mediterranean. In 1874 Lenormant succeeded Beulé as professor of archæology at the Bibliotheque Nationale. In 1881 he had been made a member of the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres.

The Origins of History

From 1880 to 1882 he published Les Origines de l’histoire d’après la Bible et les traditions des peuples orientaux (“The Origins of History According to the Bible and the Traditions of the Oriental Peoples”), a work that attained wide publicity. Lenormant thought it impossible to maintain a unity of composition in the books of the Pentateuch. He held that there were certain traces of two distinct original documents; the Elohistic and the Jehovistic which served as a basis for the final compiler of the first four books of the Pentateuch.[1] According to him, the first chapters of Genesis are a “book of prehistory” as told by the Israelites from generation to generation since the time of the archfathers; in all fundamental facts the narrative agrees with the sacred books of the ancient peoples of the Euphrates and Tigris. For Lenormant, the inspiration lies in the absolutely new spirit that fills the account with life, although in its design the written work is quite similar to the stories told by the neighboring peoples. Four years after his death, the book was put on the index on December 19, 1887; at the same time, in the introduction, he affirms his attachment to the Catholic faith.

Illness and Death

Lenormant had a perfect passion for exploration. Besides his early expeditions to Greece, he visited the south of Italy three times with this object, and it was while exploring in Calabria that he met with an accident which ended fatally in Paris after a long illness in 1883. On a research trip to Calabria Francois Lenormant had a serious accident and died in Paris on 9 December 1883, at the age of almost 47, from the consequences of this accident after a long illness.

Cracking Ancient Codes: Cuneiform Writing – with Irving Finkel, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Mayence, F. (1910). François Lenormant. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved January 14, 2017 from New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09151a.htm

- [2] Francois Lenormant, French assyriologist, at Britannica online

- [3] François Lenormant at Wikidata

- [4] Henry Rawlinson and the Mesopotamian Cuneiform, SciHi Blog, April 11, 2015.

- [5] At the Beginning was a Bet – Georg Friedrich Grotefend and the Cuneiform, SciHi Blog, June 9, 2013.

- [6] Carsten Niebuhr and the Decipherment of Cuneiform, SciHi Blog, March 17, 2013.

- [7] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Lenormant, François“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 421.

- [8] Works by or about François Lenormant at Internet Archive

- [9] Cracking Ancient Codes: Cuneiform Writing – with Irving Finkel, 2019, The Royal Institution @ youtube

- [10] François Lenormant, in: Johann Samuel Ersch, Johann Gottfried Gruber (Hrsg.): Allgemeine Encyclopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste, 2. Sektion, 43. Teil (1889), S. 82f.

- [11] François Lenormant at bnf.data

- [12] Timeline of writing systems and alphabets, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #23 | Whewell's Ghost