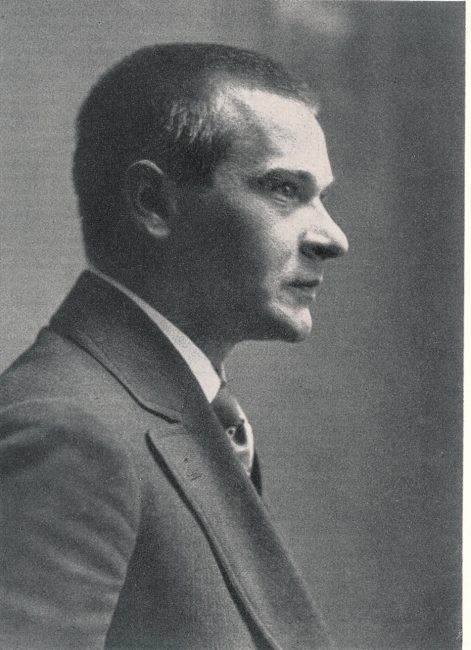

Georg Trakl (1887-1914)

On February 3, 1887, Austrian poet Georg Trakl was born. Trakl is most probably the most important Austrian poet of Expressionism with strong influences of Symbolism. However, it is not possible to clearly assign his poetic works to one of the almost simultaneous currents of literary history of the 20th century.

Verwandlung

(2. Fassung)

Entlang an Gärten, herbstlich, rotversengt:

Hier zeigt im Stillen sich ein tüchtig Leben.

Des Menschen Hände tragen braune Reben,

Indes der sanfte Schmerz im Blick sich senkt.Am Abend: Schritte gehn durch schwarzes Land

Erscheinender in roter Buchen Schweigen.

Ein blaues Tier will sich vorm Tod verneigen

Und grauenvoll verfällt ein leer Gewand.Geruhiges vor einer Schenke spielt,

Ein Antlitz ist berauscht ins Gras gesunken.

Hollunderfrüchte, Flöten weich und trunken,

Resedenduft, der Weibliches umspült.

Metamorphosis [2] (2nd version)

Alongside gardens, autumnal, red-scorched:

Here a proper life appears in the stillness.

The hands of mankind are bearing brown grapevines,

While the gentle pain’s brought down by the view.With evening: footfalls go through the black land:

An imago in a silence of red beech.

A blue creature wishes to bow before death

And an empty robe loathsomely decays.Something that calms plays outside a tavern,

A face has sunken besotted in the grass.

Elderberries, the flutes mellow and drunken,

A mignonette smell washing things female.

Georg Trakl’s Early Years

Georg Trakl grew up in Salzburg as the fifth of seven siblings within an upper middle class family. The father, Tobias Trakl, owned an ironmongery. The mother, Maria Catharina (née Halik), who was partly of Czech descent, had a difficult relationship with her children and was a drug addict. Outwardly she led the life of a normal bourgeois woman. Georg Trakl spent his childhood and youth in Salzburg, where he was raised by a French governess together with his siblings. The governess, Marie Boring, was in the service of the family for 14 years and played an important role for the children as a mother substitute. She was a strict Catholic and taught the children the French language, and often read French literature and magazines with them. It was at this time that Trakl first came into contact with French literature, which influenced his later complete works. Above all, influences from Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire are clearly visible in Trakl’s literary work.[1] An intimate relationship developed with his four and a half years younger sister Margarethe, called Gretl. Trakl saw in her a reflection of himself. The poet referred to his sister in many places in his poems. In many biographies an incestuous relationship is also suspected.

Further Education and First Publications

From 1897 to 1905 Trakl attended the humanistic state grammar school in Salzburg. His first literary attempts began around 1904, when he joined the Salzburg poetry circle “Apollo”. In 1905 he again failed to reach the class goal and ended his school career without a Matura (Austrian high school diploma). During this time, Trakl’s first experiments with drugs (chloroform, morphine, opium, veronal, alcohol) also took place. In September 1905 he began a three-year apprenticeship in the Salzburg pharmacy “Zum weißen Engel“, which made it easy for him to obtain narcotics.. At the end of March 1906 Trakl’s play Totentag (Day of the Dead) was premiered at the Salzburg City Theatre, and in September 1906 Fata Morgana. However, the two one-act plays met with little approval, so the poet destroyed them soon afterwards. In the same year the prose work Traumland (Dreamland) was published. Around 1907 Trakl fell into a first creative crisis because of his failures, which led to increased drug consumption. On February 26, 1908, Trakl’s first poem Das Morgenlied (The Morning Song) was published. In the same year he completed his practical training as a pharmacist and began to study pharmacy in Vienna. Further publications followed, now also outside Salzburg. For example, Devotion, Completion and A Passer-by were published in the New Vienna Journal.

Melancholic Lyricism

The murderer smiles palely in wine,

Death’s horror grips the sick.

Excoriated and naked, the nun prays

Before the Savior’s agony on the cross.The mother sings quietly in sleep.

Peacefully the child looks into the night

With eyes that are completely truthful.

In the whorehouse laughter rings.By candlelight down in the cellar hole

The dead one paints with white hand

A grinning silence on the wall.

The sleeper whispers still.

– Georg Trakl, Romance in the Night

After the death of his father in 1910, the family got into financial difficulties. Trakl nevertheless graduated with a master’s degree in pharmacy and shortly afterwards entered military service as a one-year volunteer with a medical department in Vienna. At this time Trakl fell more and more into depression and drug excesses. However, he also achieved a poetic breakthrough into a more mature, melancholy lyricism that would characterize his work from that point on. After the end of his military year, he tried to gain a foothold as a pharmacist, which he never really succeeded in doing, but led him to Innsbruck in 1911. Through his childhood friend Erhard Buschbeck, Trakl also met his great patron Ludwig von Ficker there in 1912, in whose renowned bi-monthly magazine Der Brenner his poems were published regularly from then on. In addition, he became acquainted with some important people of the Austrian literary and artistic scene

A Chain of Illness and despair

The black snow that runs from the rooftops;

A red finger dips into your forehead

Blue flakes sink into the bare room,

These are the dead mirrors of lovers.

– Georg Trakl, Delirium (1913)

In 1912 Georg Trakl got a job as a military medicine officer in Vienna, which he gave up after a few weeks. In search of a more suitable position and publishers for his poems, he subsequently commuted between Salzburg, Vienna and Innsbruck. After his manuscript Gedichte (Poems) was published in 1913, Trakl travelled to Venice and held his first and only public reading in Innsbruck at the end of the year. Despite his literary successes, the poet spoke of a “chain of illness and despair” that haunted his life. In March 1914 Trakl travelled to Berlin to visit his sister Margarethe, who had suffered a miscarriage. There he also met Else Lasker-Schüler, who also assisted his sister. Back in Innsbruck, Trakl continued to work on his second book of poems, Sebastian im Traum, which he himself was still working on for publication.

World War I and Death

In August 1914 the First World War broke out. Trakl was drafted into the army as a military pharmacist. He experienced the Battle of Gródek in September 1914 as a medical lieutenant. He had to care for almost one hundred seriously wounded in bad conditions alone and without sufficient material. For two days and two nights he worked in a military hospital that was later described in the press as one of the “death pits of Galicia”. Trakl had no way of helping the dying, which plunged him into despair. According to the testimony of his superiors, half an hour before the battle 13 Ruthenians had been hanged on trees in front of the tent. Trakl then suffered a nervous breakdown. In the poem of the same name, Grodek, he processed his war experience a few days before his death. Trakl was prevented from attempting to shoot himself by comrades and after an attempted escape was admitted to a Krakow military hospital to observe his mental state. On the evening of November 3, 1914, he died there of cardiac arrest after taking an overdose of cocaine. Whether this was an accident or suicide is unclear. Trakl’s second volume of poetry Sebastian im Traum was published posthumously in spring 1915.

Trakl’s Poetry

Decay

In the evening, when the bells ring peace,

I follow the wonderful flights of birds,

That in long rows, like devout pilgrim-processions,

Disappear into the clear autumn vastness.Wandering through the dusk-filled garden

I dream after their brighter destinies

And hardly feel the motion of the hour hands.

Thus I follow their journeys over the clouds.Then a whiff of decay makes me tremble.

The blackbird complains in defoliated branches.

The red wine sways on rusty trellises.Meanwhile like the death-dances of pale children

Around dark fountain edges that weather,

Shivering blue asters bend in the wind.

– Georg Trakl (1909)

Following on from Rimbaud, Verlaine and Baudelaire, Trakl’s poems darken the reader’s mind with dark images of evening and night, dying, death and passing away. Only sometimes does a thin ray of light of hope stray into his scenes, much like the “shivering blue asters” from his poem “Verfall” (Decay) , in which he tried to capture the melancholy mood of an autumn evening in 1909.[7] In Trakl’s work the mood and colours of autumn predominate, dark images of evening and night, dying, death and passing away. Although the poems are rich in biblical-religious references, and many are suited to a contemplative openness to transcendence, the light of salvation rarely breaks into the darkness. The frequent use of colour symbolism (mostly blue – in more than half of all poems, then red and brown) initially served to describe real things, later the colours often took on a life of their own as independent metaphors, for example: “Melancholy blue in the womb of the woman” (from: Anblick). While Trakl’s very earliest poems are more philosophical and do not deal as much with the real world, most of his poems are either set in the evening or have evening as a motif. Silence is also a frequent motif in Trakl’s poetry, and his later poems often feature the silent dead, who are unable to express themselves.

If you want to learn more about Georg Trakl (and speak German), you might be interested in a lecture by Lutz Seiler on “Die dunkle Seite des Mondes‹. Über Georg Trakl, Stefan George und Pink Floyd”.

Lutz Seiler: ›Die dunkle Seite des Mondes‹. Über Georg Trakl, Stefan George und Pink Floyd, [9]

Selected Bibliography:

- Gedichte (Poems), 1913

- Sebastian im Traum (Sebastian in the Dream), 1915

- Der Herbst des Einsamen (The Autumn of The Lonely), 1920

- Gesang des Abgeschiedenen (Song of the Departed), 1933

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Charles Baudelaire and the Flowers of Evil, SciHi Blog

- [2] “Uncommon Poems and Versions by Georg Trakl”, trans. James Reidel, Mudlark No. 53, 2014

- [3] Translated Poetry of Georg Trakl at RedYucca

- [4] Twenty Poems, trans. by James Wright and Robert Bly — PDF file of a 1961 translation

- [5] The Complete Writings of Georg Trakl in English – translations by Wersch and Jim Doss

- [6] Works by or about Georg Trakl at Internet Archive

- [7] Georg Trakl – Rausch und Poesie, Biblionomicon, 03-02-2016

- [8] Georg Trakl at Wikidata

- [9] Lutz Seiler: ›Die dunkle Seite des Mondes‹. Über Georg Trakl, Stefan George und Pink Floyd, Mosse LEctures @ youtube

- [10] Timeline of Georg Trakl, via Wikidata