Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772)

On March 29, 1772, Swedish scientist, philosopher, theologian, and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg passed away. He is best known for his book on the afterlife, Heaven and Hell (1758). From Swedenborg’s inventive and mechanical genius came his method of finding terrestrial longitude by the Moon, new methods of constructing docks and even tentative suggestions for the submarine and the airplane. Swedenborg had a prolific career as an inventor and scientist. In 1741, at age 53, he entered into a spiritual phase, in which for the remaining 28 years of his life, he wrote more or less theological works.

“All religion relates to life, and the life of religion is to do good.”

– Emanuel Swedenborg, The Doctrine of the New Jerusalem Concerning Life

Emanuel Swedenborg – Early Years ans Grand Tour

Emanuel Swedenborg was born as Emanuel Swedberg was born on January 29, 1688, as third of nine children to his father Jesper Swedberg, who descended from a wealthy mining family, and Sarah Behm Swedberg. Jesper Swedberg took interest in the beliefs of the dissenting Lutheran Pietist movement, which emphasized the virtues of communion with God rather than relying on sheer faith. While controversial, the beliefs were to have a major impact on his son Emanuel’s spirituality. Jesper Swedberg would later become professor of theology at Uppsala University and Bishop of Skara.

From 1703 to 1709 Swedenborg lived in the house of Erik Benzelius the younger, a prominent priest, theologian, librarian, and one of Sweden’s important Enlightenment figures. Swedenborg completed his university courses at Uppsala in 1709, where he studied mechanics, geography, astronomy, and mathematics. In 1710, he started his grand tour through the Netherlands, France, and Germany, before reaching London, where he would spend the next four years, studying physics, mechanics and philosophy and read and wrote poetry.

Return to Sweden

In 1715 Swedenborg returned to Sweden, where he devoted himself to natural science and engineering projects for the next two decades. A first step was his meeting with King Charles XII of Sweden in Lund, in 1716. The Swedish inventor Christopher Polhem,[10] who became a close friend of Swedenborg, was also present. Swedenborg’s purpose was to persuade the king to fund an observatory in northern Sweden. However, the king did not consider this project important enough, but did appoint Swedenborg assessor-extraordinary on the Swedish Board of Mines (Bergskollegium) in Stockholm. For the next 30 years, Swedenborg’s main work was concentrated in the Swedish metal-mining industry. His engineering skill earned him a wide reputation.[1]

The Northern Daedalus

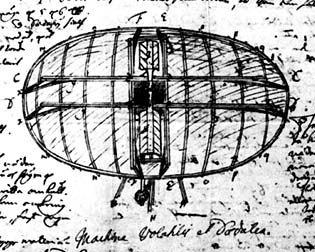

From 1716 to 1718, Swedenborg published a scientific periodical entitled Daedalus Hyperboreus (The Northern Daedalus), a record of mechanical and mathematical inventions and discoveries. One notable description was that of a flying machine, the same he had already been sketching a few years earlier. In 1718, he published an article that attempted to explain spiritual and mental events in terms of minute vibrations or “tremulations”. In 1719, the family name was changed to Swedenborg when the family was ennobled.

The Flying Machine, sketched in Swedenborg’s notebook from 1714.

Opera Philosophica et Mineralia

n 1721, Swedenborg issued a voluminous work in which he attempted to demonstrate the geometrical character of physics and chemistry. He spent the next 13 years researching and writing a three-volume work on the nature of physics, Opera philosophica et mineralia, published at Leipzig in 1734, where he tries to conjoin philosophy and metallurgy. He conceived of the atom as a particle vortex, each particle being composed of its own inner motions. This theory approximated the electron-nucleus framework of the atom in modern physics.[2]

Speaking in Public

In 1724, he was offered the chair of mathematics at Uppsala University, but he declined and said that he had mainly dealt with geometry, chemistry and metallurgy during his career. He also said that he did not have the gift of eloquent speech because of a stutter, which forced him to speak slowly and carefully. Moreover, there are no known occurrences of his speaking in public.

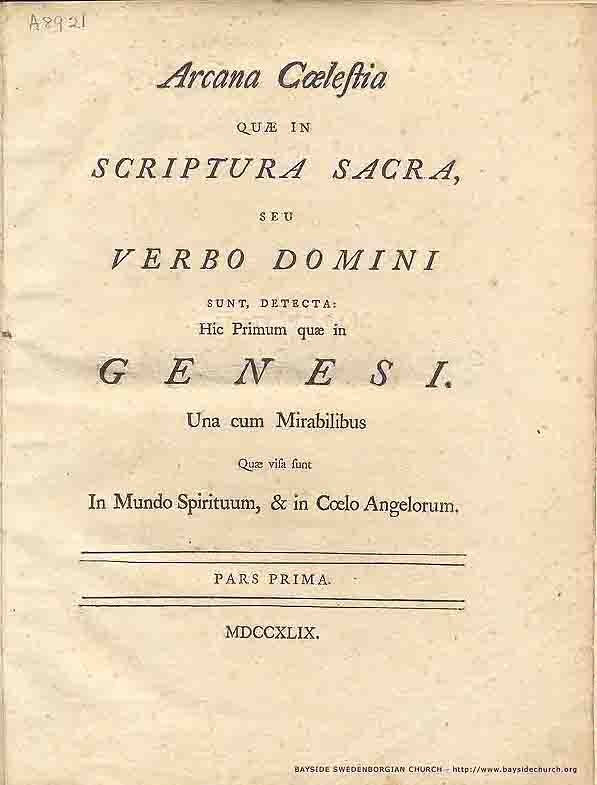

Arcana Cœlestia, first edition (1749), title page

Anatomy and Physiology

During the 1730s, Swedenborg undertook many studies of anatomy and physiology. He had the first anticipation, as far as known, of the neuron concept. It was not until a century later that science recognized the full significance of the nerve cell. He also had prescient ideas about the cerebral cortex, the hierarchical organization of the nervous system, the localization of the cerebrospinal fluid, the functions of the pituitary gland, the perivascular spaces, and the association of frontal brain regions with the intellect. In some cases his conclusions have been experimentally verified in modern times.

Towards Spiritual Matters

“Angels never attack, as infernal spirits do. Angels only ward off and defend”

– Emanuel Swedenbo0rg, Arcana Coelestis (1749-1756)

In the late 1730s Swedenborg became increasingly interested in spiritual matters and was determined to find a theory which would explain how matter relates to spirit. Swedenborg’s desire to understand the order and purpose of creation first led him to investigate the structure of matter and the process of creation itself. In the Principia (1734) he outlined his philosophical method, which incorporated experience, geometry (the means whereby the inner order of the world can be known), and the power of reason. In the same year he published de Infinito (On the Infinite), where he attempted to explain how the finite is related to the infinite, and how the soul is connected to the body. He was aware that it might clash with established theologies, since he presents the view that the soul is based on material substances.

Church of the New Jerusalem

In 1743, at age 55, Swedenborg requested a leave of absence to go abroad. His purpose was to gather source material for Regnum animale (The Animal Kingdom, or Kingdom of Life), in which he aimed to explain the soul from an anatomical point of view. He had planned to produce a total of seventeen volumes. Beginning in 1743 and continuing throughout 1744, Swedenborg experienced intense dreams and visions at night, which he recorded in his personal diary. Many of them revolved around a sense of spiritual unworthiness, a feeling that he had to purify himself of sin.[3] Although not a theologian in the strict sense, he was an outstanding philosopher or theological speculator. Utilizing some basic Christian truths, Swedenborg elaborated, partly on a scientific basis, partly on a philosophical basi, a theory of God, of man, and of divine revelation and redemption. On the basis of these theorizings, the Church of the New Jerusalem was founded in 1784.[2]

The Secrets of Heaven

In 1747, he refused a promotion that had been offered to him, instead petitioning the king to be released from his service on the Board of Mines so he could devote himself full time to theological writing. He took up afresh his study of Hebrew and began to work on the spiritual interpretation of the Bible with the goal of interpreting the spiritual meaning of every verse. He devoted all his energy to complete his opus magnum, Arcana Cœlestia (Secrets of Heaven) as the basis of his further theological works. The work was originally was published anonymously in eight volumes between 1749 and 1756, and Swedenborg was not identified as the author until the late 1750s. It attracted only little attention, as few people were able to understand its meaning. Although Swedenborg intended to go through every verse of the entire Bible, he never did so. Instead, he continued his publications with Heaven and Hell, a description of the afterlife and the lives of its inhabitants; Other Planets, which describes the beings that live on other planets; Last Judgment and New Jerusalem. There, he writes that the Last Judgment is not a future event that will mark the end of our world, but a spiritual event where evil spirits who had managed to infiltrate heaven were cast down to hell, allowing human beings on earth and in heaven to receive spiritual truths more clearly.

Death

Swedenborg passed away on March 29, 1772, in London, in the aftermath of a stroke from which he never fully recovered. His visions and religious ideas have been a source of inspiration for a number of prominent writers, including Honoré de Balzac,[6] Charles Baudelaire,[7] Ralph Waldo Emerson,[8] William Butler Yeats,[8] and August Strindberg.[4]

“The real importance of Swedenborg lies in the doctrines he taught, which are the reverse of the gloom and hell-fire of other breakaway sects. He rejects the notion that Jesus died on the cross to atone for the sin of Adam, declaring that God is neither vindictive nor petty-minded, and that since he is God, he doesn’t need atonement. It is remarkable that this common-sense view had never struck earlier theologians. God is Divine Goodness, and Jesus is Divine Wisdom, and Goodness has to be approached through Wisdom. Whatever one thinks about the extraordinary claims of its founder, it must be acknowledged that there is something very beautiful and healthy about the Swedenborgian religion. Its founder may have not been a great occultist, but he was a great man.”

– Colin Wilson in The Occult, p. 280 (1971)

Umberto Eco in conversation with Paul Holdengräber, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Emanuel Swedenborg Biography at The Famous People

- [2] Emanuel Swedenborg at YourDictionary

- [3] About his Life at www.swedenborg.com

- [4] Emanuel Swedenborg at BritannicaOnline

- [5] Emanuel Swedenborg at Wikidata

- [6] Honoré de Balzac and the Comédie Humaine, SciHi Blog, May 20, 2013.

- [7] Charles Baudelaire and the Flowers of Evil, SciHi Blog, April 9, 2014.

- [8] Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Transcendentalism Movement, May 25, 2013.

- [9] William Butler Yeats and Modern English Literature, SciHi Blog, June 13, 2014.

- [10] Christopher Polhem anticipating the Industrial Revolution, SciHi blog

- [11] Works by or about Emanuel Swedenborg at Internet Archive

- [12] Umberto Eco in conversation with Paul Holdengräber, Intelligence Squared @ youtube

- [13] Grieve, Alexander James (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 221.

- [14] Sigstedt, Cyriel (1952). “The Swedenborg Epic: The Life and Works of Emanuel Swedenborg”. Swedenborg Digital Library.

- [15] Timeline of Occultists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazettte: Vol. #42 | Whewell's Ghost