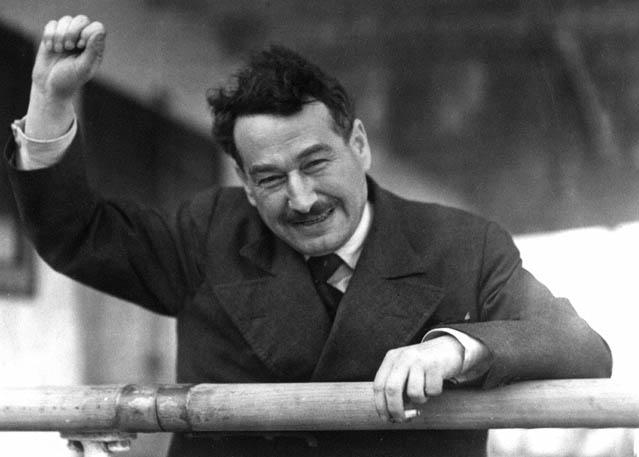

Egon Erwin Kisch (1885-1945)

On April 29, 1885, Austrian and Czechoslovak writer and journalist Egon Erwin Kisch was born. Kisch styled himself Der Rasende Reporter (The frenzied reporter) for his countless travels to the far corners of the globe and his equally numerous articles produced in a relatively short time (Hetzjagd durch die Zeit, 1925), Kisch was noted for his development of literary reportage and his opposition to Adolf Hitler‘s Nazi regime.

“And there is nothing more sensational in the world than the time you live in!”

– Egon Erwin Kisch, Der rasende Reporter. Vorwort zur 1. Ausgabe, 1925

Crime and the Lives of the Poor

Egon Erwin Kisch was born into a wealthy, German-speaking Sephardic Jewish family in Prague, at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to Hermann Kisch, owner of a textile shop, and his wife Ernestine, née Kuh. He briefly attended the German Technical College and the German University of Prague before serving for a year in the Imperial army and began his journalistic career as a reporter for Bohemia, a Prague German-language newspaper, in 1906. His early work is characterised by an interest in crime and the lives of the poor of Prague, taking Jan Neruda, Émile Zola and Charles Dickens‘s Sketches by Boz as his models. His most notable story of this period was his uncovering of the spy scandal involving Alfred Redl.[5,6] Working for Bohemia, he was developing his skills in reportage journalism as a form of social critique intended to arouse public concern.

Write that down, Kisch!

At the outbreak of World War I, Kisch was called up for military service and became a corporal in the Austrian army. He fought on the front line in Serbia and the Carpathians and his wartime experiences were later recorded in Schreib das auf, Kisch! (Write That Down, Kisch!) (1929). He was briefly imprisoned in 1916 for publishing reports from the front that criticised the Austrian military’s conduct of the war, but nonetheless later served in the army’s press quarters along with fellow writers Franz Werfel and Robert Musil.[7] However, the war radicalized Kisch. He deserted in October 1918 as the war came to an end and played a leading role in the abortive left-wing revolution in Vienna in November of that year. Soon after, he left for Berlin where he became involved in organizing ‘popular front’ bodies on behalf of the Comintern and remained a Communist for the rest of his life.[1]

The Raging Reporter

Between 1921 and 1930 Kisch, though a citizen of Czechoslovakia, lived primarily in Berlin, where his work found a new and appreciative audience. In books of collected journalism such as Der rasende Reporter (The Raging Reporter) (1924), he cultivated the image of a witty, gritty, daring reporter always on the move, a cigarette clamped doggedly between his lips. His work and his public persona found an echo in the artistic movement of Neue Sachlichkeit, a major strand in the culture of the Weimar Republic. Then followed accounts of trips to the Soviet Union (1926), the United States of America (1929) and China (1933) — all written from the Communist point of view, but sparkling with wit and colour, which established his reputation as the most significant and successful writer of reportage in German.[1] From 1925 onwards Kisch was a speaker and operative of the communist international and a senior figure in the publishing empire of the West European branch of the Comintern run by communist propagandist Willi Münzenberg. In 1928 Kisch was one of the founders of the Association of Proletarian-Revolutionary Authors.

“The reporter has no tendency, no justification and no point of view. He has to be an impartial witness and give impartial testimony.”

– Egon Erwin Kisch, Der rasende Reporter. Vorwort zur 1. Ausgabe, 1925

The Horrors of the Nazi Takeover

Whereas in his earlier collections of reportage he had explicitly stated that a reporter should remain impartial, Kisch came to feel that it was necessary for a writer to engage politically with what he was reporting on. He was a leading opponent of Adolf Hitler and he criticised attempts to portray him as a brave soldier.[2] On 28 February 1933, the day after the Reichstag fire, Kisch was one of many prominent opponents of Nazism to be arrested. His works were banned and burnt in Germany, but he continued to write for the Czech and émigré German press, bearing witness to the horrors of the Nazi takeover.

Failing in Scottish Gaelic

In 1934, Kisch visited Australia as a delegate to an anti-fascist conference, but was refused entry from the ship Strathaird at Fremantle and Melbourne because of his previous exclusion from the UK due to his “known subversive activities”. When jumping from the deck of his ship onto the quayside at Melbourne, he broke his leg and was bundled back on board but this dramatic action mobilized the Australian left in support of Kisch. However, Kisch was to be released, but under the Australian Immigration Restriction Act 1901, visitors could be refused entry if they failed a dictation test in any European language. As soon as Kisch was released, he was re-arrested and was one of the very few Europeans to be given the test; he passed the test in various languages but finally failed when he was tested in Scottish Gaelic.

From Spain to Mexico

In 1937 and 1938, Kisch was in Spain, joining left-wingers from across the world who had been drawn by the Spanish Civil War. He travelled across the country, speaking in the Republican cause, and his reports from the front line were widely published. Following the Munich Agreement of 1938 and the subsequent Nazi occupation of Bohemia, Kisch was unable to return to the country of his birth. Once war broke out, Paris, which he had made his main home since 1933, also became too dangerous for an outspoken Jewish communist. In late 1939, Kisch and his wife sailed for New York where, once again, he was denied entry and after being kept on Ellis Island for six months he was allowed to move to Mexico in October 1940, where he remained for the subsequent five years among a circle of European communist refugees, notable among them Anna Seghers.

Sensation Fair

Kisch continued to write, producing a book on Mexico and a memoir, Marktplatz der Sensationen (Sensation Fair) (1941). In March 1946, after troubles in securing a Czechoslovak visa, he was able to return to his birthplace. Immediately after the return he started to travel around the country and work as a journalist again. Kisch died two years after his return to Prague in 1948, shortly after the Communist party seized complete power.

An introduction to mobile phone journalism | RTS Futures, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Carolyn Rasmussen: Kisch, Egon Erwin (1885–1948), in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 15, (MUP), 2000

- [2] Egon Erwin Kisch, at Spartacus Educational

- [3] [in German] Egon-Erwin-Kisch-Sammlung im Archiv der Akademie der Künste, Berlin.

- [4] Egon Erwin Kisch at Wikidata

- [5] J’Accuse – Émile Zola and the Dreyfus Affaire, SciHi Blog

- [6] Charles Dickens – Famous Writer and Critic of the Victorian Era, SciHi Blog

- [7] Robert Musil and the Man without Qualities, SciHi Blog

- [8] An introduction to mobile phone journalism | RTS Futures, Royal Television Society @ youtube

- [9] Cochrane, Peter (2008). The Big Jump: Egon Kisch in Australia. Commonwealth History Project. The National Centre for History Education.

- [10] Gatterer, Joachim (2019): “History, literature and propaganda: Egon Erwin Kisch in the Spanish Civil War, in: Alía Miranda, Francisco/Higueras Castañeda, Eduardo/Selva Iniesta, Antonio (ed.): Hasta pronto, amigos de España. Las Brigadas Internacionales en el 80 aniversario de su despedida de la Guerra Civil (1938–2018), Albacete: CEDOBI 2019, 249–261.

- [11] Spector, Scott (2006). Kisch, Egon Erwin. The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

- [12] Timeline of Marxist Journalists, according to DBpedia and Wikidata