Dorothy Hodgkin (1910 – 1994)

On July 29, 1994, British chemist and Nobel Laureate Dorothy Mary Hodgkin passed away. She advanced the technique of X-ray crystallography, a method used to determine the three-dimensional structures of biomolecules. Among her most influential discoveries are the confirmation of the structure of penicillin.

“Would it not be better if one could really ‘see’ whether molecules…were just as experiments suggested?”

– Dorothy Hodgkin, as quoted in [11]

Dorothy Hodgkin Background

Dorothy Crowfoot (later Hodgkin) was the eldest of four daughters of an English colonial officer in Cairo. Her parents, John Winter Crowfoot (1873-1959) and Grace Mary Hood (1877-1957), traveled a lot and therefore raised their children with relatives in England. Her interest in chemistry started around the age of only 10. Her parents were involved in education projects in Egypt and Sudan and during a visit, their daughter was allowed to study and analyze some chemicals with a friend of the family. Also, when she was attending the Sir John Leman School, she was allowed to join the boys as they studied chemistry. By the end of her early schooling, she had already decided that chemistry was something she wanted to pursue. Also, it is assumed that her time in Sudan played a big role in her future career. She was able to help with excavations and studied pebbles with a portable mineral analysis kit, which pushed her fascination and interest in crystals and minerals. This experience almost made her give up chemistry and replace it with archaeology instead.

From Archaeology to Chemistry

Then she was given a copy of “Concerning the Nature of Things” by Sir William Henry Bragg when she was 15, and she was intrigued at the thought of being able to study the properties of atoms and molecules using x-rays. She began studying chemistry at Somerville College, Oxford University and continued at the University of Cambridge to earn her PhD with John Desmond Bernal, who had worked for five years with the senior Bragg [1]. Hodgkin and Bernal used X-ray crystallography to determine the three-dimensional structure of several complex organic molecules important to the functioning of living organisms [2]. She was entranced by the “elegance” of the then new X-ray structure analysis and, using this method, took diffraction images of many biologically relevant molecules for the first time, including pepsin (1934) and cholesterol (1941). In 1932 Dorothy Crowfoot returned to Oxford as a teacher. In 1937 she married the political scientist Thomas Lionel Hodgkin, with whom she had three children.

Penicillin

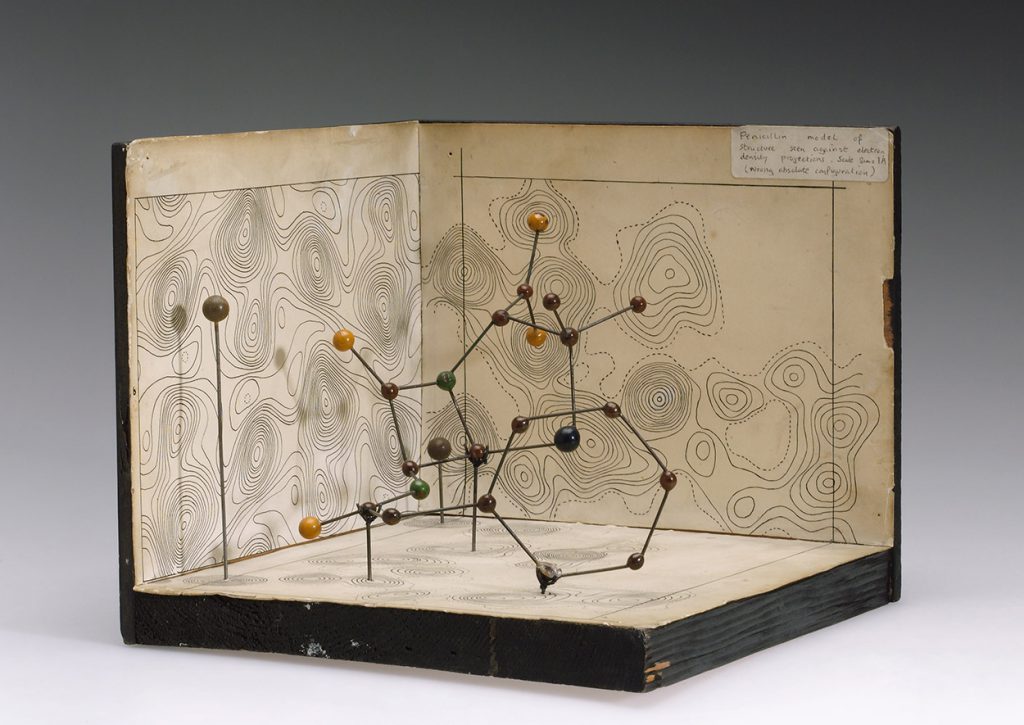

To Hodgkin’s most important contributions to the science of chemistry belongs presumably the determination of the structures of penicillin, insulin, and vitamin B12. She determined the exact structure of penicillin in 1945. The results contradicted general scientific thought at the time and therefore put researchers on the right path to developing further and more sophisticated uses for penicillin-based antibiotics, including the development of semisynthetic versions. In the 1950s, the scientist and her colleagues published an analysis of vitamin B12 which expanded the understanding of how this vital nutritional component functions and how it is utilized by the human body. Hodgkin spent years honing and improving the available methods to penetrate the mysteries of ever-more complicated structures. After 35 years of work, the internal structure of insulin was solved [3]. She received the Nobel Prize in chemistry “for her determinations by X-ray techniques of the structures of important biochemical substances”. Also, she was the third woman ever to win the prize in chemistry, after Marie Curie and Irène Joliot-Curie [2].

Molecular model of Penicillin by Dorothy Hodgkin, c.1945. Front three quarter. Graduated grey background.

Further Activities and Later Years

Next to her research studies, Dorothy Hodgkin was highly involved in humanitarian projects including the welfare of scientists and people living in nations defined as adversaries by the United States and the United Kingdom in the 1960s and 1970s, for example, the Soviet Union, China, and North Vietnam. Shortly after the birth of her first child, she fell seriously ill with rheumatoid arthritis, but this did not stop her research. In 1947 she was the third woman to be admitted to the exclusive Royal Society. In 1958 she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, in 1970 to the Royal Society of Edinburgh[3] and in 1971 to the National Academy of Sciences. From 1962 Dorothy Hodgkin was a member of the Pugwash Conference and actively promoted understanding between scientists from East and West. Among her students at Oxford in 1946/47 was Margaret Thatcher who wrote her thesis on chemistry with her.

(4 of 8) Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, “On Continuing the X-ray Analysis of Insulin”, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Dorothy Hodgkin at Famous Scientists

- [2] Dorothy Hodgkin at the Chemistry Heritage Foundation

- [3] Guy Dodson: Biografical Memoirs Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin at Royal Society

- [4] Dorothy Hodgkin at the Nobel Prize Page

- [5] William Lawrence Bragg and X-Ray Chrystallography

- [6] Alexander Fleming and the Penicillin

- [7] Ernst Boris Chain and his Research on Antibiotics

- [8] Dorothy Hodgkin at Wikidata

- [9] Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, “On Continuing the X-ray Analysis of Insulin”, American Crystallographic Association @ youtube

- [10] Works by or about Dorothy Hodgkin at Internet Archive

- [11] Sharon Bertsch McGrayne (1998). Nobel Prize women in science: their lives, struggles, and momentous discoveries. Joseph Henry Press.

- [12] Timeline of Dorothy Hodgkin via Wikidata