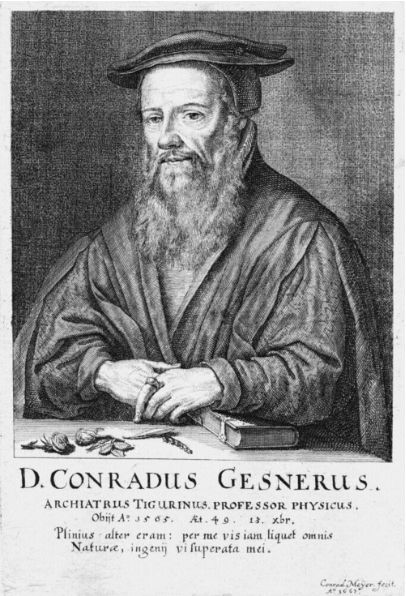

Conrad Gessner (1516–1565), Engraving by Conrad Meyer, 1662

On March 26, 1516, Swiss naturalist and bibliographer Conrad Gessner was born. His five-volume Historiae animalium (1551–1558) is considered the beginning of modern zoology, and the flowering plant genus Gesneria is named after him. He is considered as one of the most important natural scientists of Switzerland and was sometimes referred to as the ‘German Pliny‘.

The Godson and Protege of Zwingli

Conrad Gessner was born and educated in Zürich, Switzerland as the son of Ursus Gessner, a poor furrier, and his wife Agathe. The death of his father at the Battle of Kappel in 1531 as the wars spawned by the Reformation had reached also the Swiss cantons, left Conrad in a rather desolate condition. Fortunately, he happened to be also the godson and protegé of the Swiss Protestant reformer Huldrych Zwingli, and with the help of the Protestant classics scholar Oswald Myconius and Heinrich Bullinger, the successor of Zwingli, Gessner was enabled to continue his studies at the universities of Strassburg and Bourges, where he displayed great linguistic talent and interest in nature. In 1535, religious unrest drove him back to Zürich, where he made an imprudent marriage.

Academic Career and Bibliotheca Universalis

In 1537 Gessner received a professorship in Greek at Lausanne and speedily compiled single-handedly an entire dictionary in that language. Here he had leisure to devote himself to scientific studies, especially botany. The city physician of Zurich prevailed upon the young scholar to resume his medical studies so after wandering across France, Gessner settled down at the medical school of Montpellier and became a doctor of medicine. At about 1540 Gessner began teaching Aristotelian physics at the Collegium Carolinium, the precursor of the University of Zürich. In his spare time he composed his Bibliotheca universalis, a vast encyclopedia in which he listed alphabetically all of the authors, who had written in Greek, Latin, and Hebrew, with a listing of all their books printed up to that time. This work made Gessner famous, and offers of scholarly employment poured in, including one from the Fuggers, the richest family of Europe. However, the offer provided by the famous bankers attached the condition that Gessner must embrace Catholicism, which he refused. Thereafter, he spent the rest of his life as a practicing physician at Zurich, leaving only for short expeditions to study flora and fauna.

Unicorn (Monoceros). Conrad Gesner, Historiae Animalium; liber primus, qui est de quadrupedibus viviparis, Zurich, 1551.

Gessner’s Historiae Animalium

Gessner also wrote Mithridates de differentis linguis (1555), an account of approximately 130 different languages. In addition, he wrote voluminously about plants, although most of his botanical works were published posthumously. His magnum opus, however, was the Historiae animalium (“Accounts of Animals“, 1551–1558 and 1587), a 4,500-page encyclopedia of animals, now regarded as the starting point of modern zoology. It was also the first printed work to include illustrations of fossils. Gessner attempted to list and to describe all of the world’s animals in most possible detail. He tried not only to give an account of animals as denizens of the natural world, but moreover also to convey their place within literary tradition. There are many anecdotes, and the names of animals are given in various languages. Knowledge derived from ancient sources, in particular Aristotle, Pliny, Aelian, and the Old Testament, was combined with folklore and with information from medieval scholars such as Albertus Magnus.[6] Thus, the book contains many accounts of mythical creatures, too. For example, the basilisk and the unicorn are discussed alongside real animals such as foxes or porcupines. One of the major achievements of Gessner lies in his new emphasis on observation and accurate description that had been lacking in the works of earlier scientists, who largely accepted whatever had been passed on to them from the ancient and authoritative sources.

Later Life

Conrad Gessner received an imperial patent of nobility in 1564. In his manifold works, Gessner can be recognized as one of the most versatile and productive scholars of Switzerland, who distinguished himself in many areas of science. In 1565 the plague, which has been identified from Gessner’s description as a form of pulmonary bubonic, came to Zurich, and on December 13 he passed away.

How One Man Organized All Knowledge, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] “Konrad von Gessner.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004. Encyclopedia.com. 25 Mar. 2013 .

- [2] Image Gallery: Icones Animalium from Conrad Gessner’s ‘Historiae animalium’, The Australian Museum

- [3] Scans of Conrad Gessner’s works on Mammals, Birds, Fishes, Snakes and Scorpions

- [4] Digitized works of Conrad Gessner at 1-rara.ch

- [5] Happy Birthday Conrad – #GesnerDay 2017, The Renaissance Mathematicus, March 26, 2017.

- [6] Albertus Magnus and the Merit of Personal Observation, SciHi Blog, November 15, 2015.

- [7] Conrad Gessner at Wikidata

- [8] How One Man Organized All Knowledge, trms @ youtube

- [9] Fischer, Hans (1966a). Conrad Gessner 1516–1565 (in German). Zurich: Naturforschende Gesellschaft in Zürich.

- [10] Gessner, Conrad. “Thierbuch”. HUMI (Humanities Media Interface) Project: Natural History Books. Keio University.

- [11] Westfall, Richard S. (1993). “Gesner [Gessner], Konrad”. The Galileo Project. Rice University.

- [12] Gessner, Conrad (1541) [1537]. Lexicon Graeco-Latinum, ex Phavorini Camertis Lexico. Basel: Walder

- [13] Bay, Jens Christian (1963) [1916 Bibliographical Society of America]. Conrad Gesner (1516–1565), the Father of Bibliography: An Appreciation. Kraus Reprint Corporation.

- [14] Timeline of Pre-Linnaean Botanists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Happy Birthday Conrad – #GesnerDay 2017 | The Renaissance Mathematicus