Justinian I depicted on a mosaic in the church of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy

On November 16, 534 AD, the second and final revision of the Corpus Juris Civilis, also referred to as the Codex Justinianus, a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Eastern Roman Emperor, is published. The four parts of the Codex Justinianus constitute the foundation documents of the Western legal tradition. Actually, the history and development of Roman law as the legal system of ancient Rome is spanning over a thousand years, from the early beginnings of the legendary Twelve Tables (449 BC), to the Corpus Juris Civilis (AD 529). And this is the story we will tell you today…

“In dubio pro reo.” (In case of doubt, [judge] in favour of the defendant)

– Codex Iustinianus, Digesta 50.17.125

The Law of the Twelve Tables

Long before the Roman Republic was established in 509 BC, the Romans lived by laws developed through centuries of custom. One important aspect of this early law system was the fact that this law only applied to Roman citizens and was thus ius civile, or civil law. The first legal text of ancient Rome is the Law of the Twelve Tables, dating from mid-5th century BC. The plebeian tribune, C. Terentilius Arsa, proposed that the law should be written, in order to prevent magistrates from applying the law arbitrarily. Thus, after eight years of political struggle, the plebeian social class convinced the ruling patricians to send a Roman delegation to Athens, to copy the Laws of Solon, created by the Athenian statesman Solon in the early 6th century BC. According to the the Roman historian Livy, ten Roman citizens were chosen to record the laws (decemviri legibus scribundis) and in 450 BC, the decemviri produced the laws on ten tablets, but these laws were regarded as unsatisfactory by the plebeians. A second decemvirate is said to have added two further tablets in 449 BC and the new Law of the Twelve Tables was approved by the people’s assembly. While the original Twelve Tables were destroyed during the Celtic invasions of the fourth century BC, their legacy was very strong and much of their content remained known.

Ius Civile is not enough

As the Roman republic grew and then transformed into an empire, its rulers faced the increasing challenge of governing an evermore diverse population. Thus, legal questions and disputes inevitably arose not only among Roman citizens, but with non-citizens living in or traveling through its territories, to whom the ius civile did not apply. This led to the development of the ius gentium, the law of nations, which applied to all people, foreigners and non-citizens as well as citizens. These laws common to all people were further understood to be rooted in the ius naturale, or natural law, a category of law based on the principles shared by all living creatures, humans as well as animals. By the second half of the third century BC, a new professional group of specialists trained in law, the jurists, emerged, who did not participate in administering the law, but rather focused on interpreting and generating formal opinions on the law. The Roman jurists and their scholarly writings finally elevated Roman law to its apex during the first two and a half centuries AD, which is referred to as the classical period of Roman law.

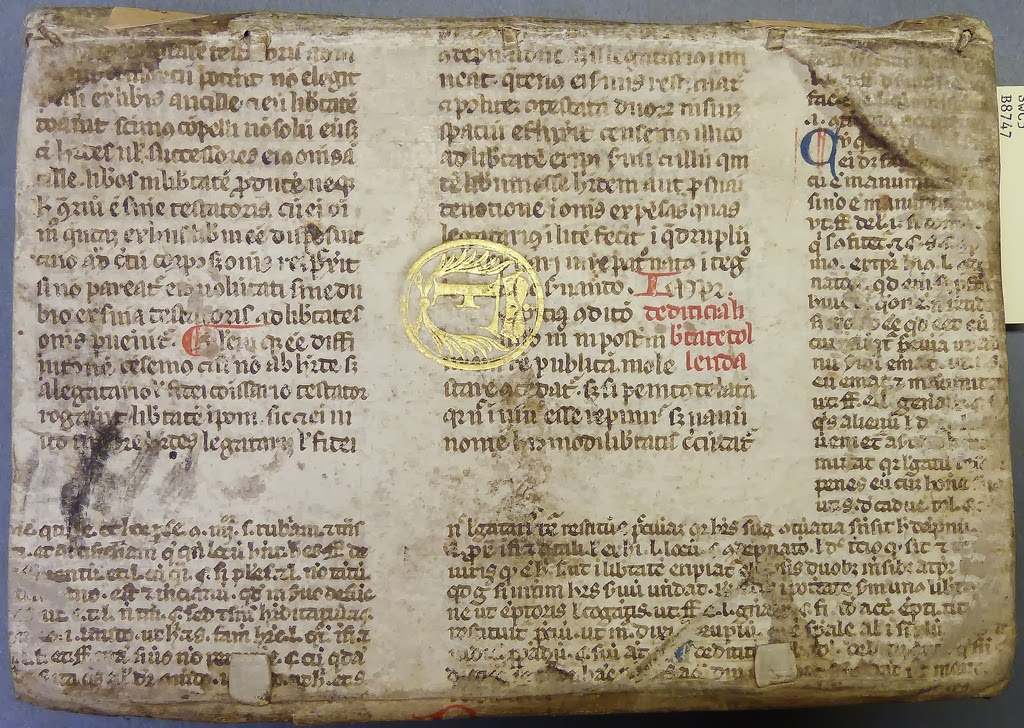

early parchment leaf from a glossed copy of the Codex Justinianus photo: http://www.flickr.com/photos/58558794@N07/9031471071/

Justinian I

By the reign of the emperor Justinian I in the 6th century AD, the vast territories of the Roman Empire in Europe, North Africa, and the East had for centuries been politically and culturally divided into the Western Empire and the Eastern Empire. While the Western Empire had endured a series of Germanic invasions leading to its final collapse by 476 AD,[3] Justinian in the Eastern Empire waged a successful campaign to reconquer some of the Western territories that had previously been lost. One way that Justinian sought to unify the empire was through law. Roman citizenship had already been extended to the empire outside of Italy in the third century AD, making all of its inhabitants “citizens of Rome” and therefore subject to its civil law. Justinian formed a commission of jurists to compile all existing Roman law into one body, which would serve to convey the historical tradition, culture, and language of Roman law throughout the empire. This compilation consisted of three different original parts: the Digest (Digesta) that collected and summarized all of the classical jurists’ writings on law and justice, the Code (Codex) that outlined the actual laws of the empire, including imperial constitutions, legislation and pronouncements, and the Institutes (Institutiones) that were only a smaller work summarizing the Digest and intended as a textbook for students of law.

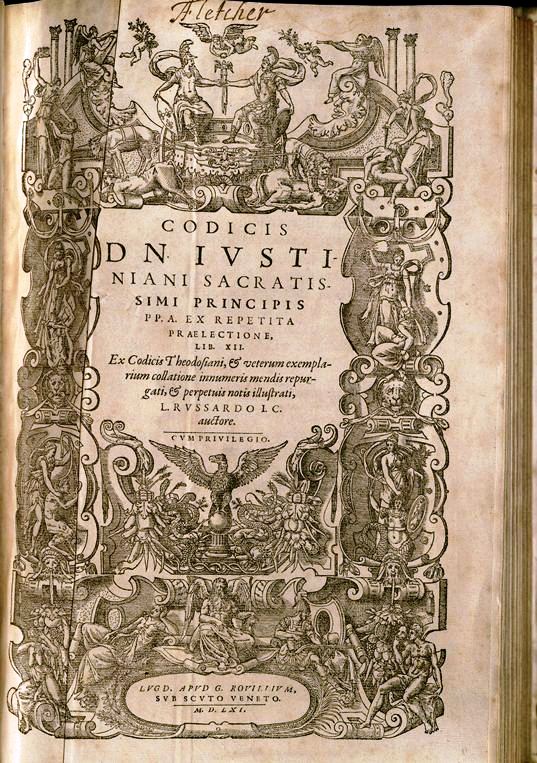

Codex Iustinianus, 1561

Codex Justinianus as Body of Civil Law

“Nomina sunt consequentia rerum.” (Names are the consequences of things.)

– Codex Iustinianus, Institutiones II 7,3

The Codex Justinianus is widely considered to be the emperor’s greatest contribution to Western history. Though largely forgotten for several centuries, Roman law experienced a revival that began at the University of Bologna in the 11th century spreading throughout Europe. Surviving manuscript copies of Justinian’s compilation were rediscovered and systematically studied and reproduced. Under the name Corpus iuris civilis (“body of civil law”), this new edition became the foundational source for Roman law in the Western tradition. All later systems of law in the West including Western continental Europe, Latin America as well as also to a lesser extend English common law borrowed heavily from it. Today, Roman law is no longer applied in legal practice. Nevertheless, knowledge of Roman law is indispensable to understand the legal systems of today. Thus, Roman law is often still a mandatory subject for law students in civil law jurisdictions.

Paul H. Friedman, 09. The Reign of Justinian, Hist210, The Early Middle Ages, 284–1000, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Roman Legal Tradition: open access journal devoted to Roman law

- [2] The Roman Laws of the Twelve Tables in English translation

- [3] The End of the Roman Empire, SciHi Blog

- [4] Rome is Burning, SciHi Blog

- [5] Augustus and the Foundation of the Roman Empire, SciHi Blog

- [6] Justinian I at Wikidata

- [7] Paul H. Friedman, 09. The Reign of Justinian, Hist210, The Early Middle Ages, 284–1000, Yale Courses @ youtube

- [8] David J.D. Miller & Peter Saaris, The Novels of Justinian: A Complete Annotated English Translation Cambridge University Press

- [9] Bruce W. Frier, ed. (2016, The Codex of Justinian. A New Annotated Translation, with Parallel Latin and Greek Text, Cambridge University Press]

- [10] Timeline of Medieval Legislators via DBpedia and Wikidata