Lévi-Strauss (1908 – 2009). Image: UNESCO/Michel Ravassard, CC BY 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

On November 28, 1908, French anthropologist and ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss was born. Lévi-Strauss’ work was key in the development of the theory of structuralism and structural anthropology. He argued that the “savage” mind had the same structures as the “civilized” mind and that human characteristics are the same everywhere.

“The entire village left the next day in about thirty canoes, leaving us alone with the women and children in the abandoned houses. [Le village entier partit le lendemain dans une trentaine de pirogues, nous laissant seuls avec les femmes et les enfants dans les maisons abandonnées.]”

– Claude Levi-Strauss, (1936), [8]

Claude Levi-Strauss – Early Years

Claude Lévi-Strauss was the son of Jewish parents. His father Raymond Urbain Elie Lévi-Strauss (1881-1953) was a portrait painter, his mother was Emma Lévi-Strauss, née Lévy (1886-1984). He grew up in Paris, France, living on a street of the upscale 16th arrondissement named after the artist Claude Lorrain, whose work he admired and later wrote about. During the First World War, he lived with his maternal grandfather, who was the rabbi of the synagogue of Versailles. He attended the Lycée Janson de Sailly and the Lycée Condorcet.

University and Brazil

He studied law and philosophy at the Sorbonne in Paris. In 1935, after a few years of secondary-school teaching, he took up a last-minute offer to be part of a French cultural mission to Brazil in which he would serve as a visiting professor of sociology at the University of São Paulo while his then wife, Dina, served as a visiting professor of ethnology. The couple lived and did their anthropological work in Brazil from 1935 to 1939. During this time, while he was a visiting professor of sociology, Claude undertook his only ethnographic fieldwork. He accompanied Dina, a trained ethnographer in her own right who was also a visiting professor at the University of São Paulo, where they conducted research forays into the Mato Grosso and the Amazon Rainforest. The exchanged collection items were shared between Brazil and France. The first exhibition at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris was entitled Expédition Dina et Claude Lévi-Strauss. Later, Dina’s contribution was almost completely forgotten, to which Claude, who subsequently remarried twice, actively contributed: In his travelogue Tristes Tropiques, he mentioned his wife, colleague, and traveling companion only once.

USA and Back to Paris

At the beginning of the war, he did military service as a liaison officer on the Maginot Line. However, he was discharged from the army in 1940 due to the racial laws of the Vichy regime, separated from his wife and emigrated from France. In 1941, he was offered a position at the New School for Social Research in New York City and granted admission to the United States. At the time, the Rockefeller Foundation supported the flight of numerous intellectuals and financed the French wing of the New School for Social Research in New York. Lévi-Strauss was exposed to the American anthropology espoused by Franz Boas, who taught at Columbia University. Lévi-Strauss returned to Paris in 1948, and at this time, he received his doctorate from the Sorbonne by submitting, in the French tradition, both a “major” and a “minor” thesis. These were The Family and Social Life of the Nambikwara Indians and The Elementary Structures of Kinship.

The Elementary Structures of Kinship

The Elementary Structures of Kinship quickly came to be regarded as one of the most important anthropological works on kinship. Lévi-Strauss argued that kinship was based on the alliance between two families that formed when women from one group married men from another, in contrast to Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown, who argued that kinship was based on descent from a common ancestor.

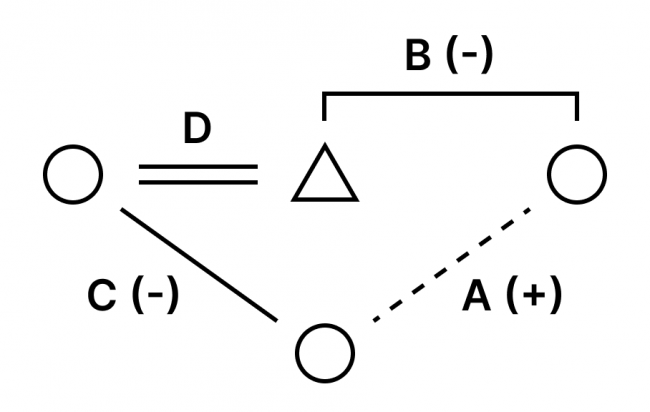

A diagram illustrating Lévi-Strauss’s theory of kinship. In such a case, one can infer that D is positive. DimenErno, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Savage Mind

Lévi-Strauss continued to publish and experienced considerable professional success and became one of France’s best known intellectuals by publishing Tristes Tropiques.[7] He was named to a chair in Social Anthropology at the Collège de France in 1959. Lévi-Strauss published Structural Anthropology, a collection of his essays which provided both examples and programmatic statements about structuralism in the same year. At the same time as he was laying the groundwork for an intellectual program, he began a series of institutions to establish anthropology as a discipline in France, including the Laboratory for Social Anthropology where new students could be trained, and a new journal, l’Homme, for publishing the results of their research. In 1962, Lévi-Strauss published what is for many people his most important work, La Pensée Sauvage, translated into English as The Savage Mind. The Savage Mind discusses not just “primitive” thought, a category defined by previous anthropologists, but forms of thought common to all human beings. The first half of the book lays out Lévi-Strauss’s theory of culture and mind, while the second half expands this account into a theory of history and social change.

Structuralism

“The idea behind structuralism is that there are things we may not know but we can learn how they are related to each other. This has been used by science since it existed and can be extended to a few other studies — linguistics and mythology — but certainly not to everything.

The great speculative structures are made to be broken. There is not one of them that can hope to last more than a few decades, or at most a century or two.”

– Claude Levi-Strauss, As quoted in his obituary, Daily Telegraph (4 November 2009)

The foundation of French ethnological structuralism is often dated to the appearance of Lévi-Strauss’ The Elementary Structures of Kinship in 1949. The basic idea is: a system of exchange controlled by marriage rules replaces natural kinship with social alliance by means of reciprocal obligation. Marriage rules are differentiated into marriage bids (society specifies from which group one should marry) and marriage bans (it is only specified from which group one may not marry). The significantly most frequent occurrence of a certain form of “wife exchange” can be explained, according to the thesis, by its preferred systematic position. It is the cross-cousin marriage, the marriage of a man with the matrilateral cross-cousin (the daughter of the mother-brother). This produces the most stable social relations. The marriage is close enough for the duty to have a social effect, but far enough away for the incest taboo to be preserved. This makes the avunculus, the mother-brother (oheim), particularly significant. This point has been criticized by Pierre Bourdieu, among others, who empirically identified this marriage case in North Africa as only one among many. For example, marriage to the matrilateral parallel cousin (the daughter of the mother’s sister) was more common in his sample. The orientation to social exchange processes has a precursor in Marcel Mauss.

Later Years

Lévi-Strauss became a world wide celebrity and also became a member of other notable academies worldwide, including the American Academy of Arts and Letters. After his retirement, he continued to publish occasional meditations on art, music, philosophy, and poetry.

Lévi-Strauss died on October 30, 2009, at the age of 100, as a result of a heart attack.[3]

Sayan Chattopahyay, noc18-hs31-Lecture 17-Structuralism: Claude Levi-Strauss, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Claude Lévi Strauss at Famous Scientists

- [2] Claude Lévi_Strauss at Britannica

- [3] Doland, Angela (4 November 2009). “Anthropology giant Claude Levi-Strauss dead at 100”. Seattle Times.

- [4] Voss, Susan M. (1977). “Claude Levi-Strauss: The Man and His Works”. Nebraska Anthropologist. 3: 21–38.

- [5] Johnson, C. (2003). Claude Levi-Strauss: The Formative Years. Cambridge University Press.

- [6] Doja, Albert (2008): “Claude Lévi-Strauss at his Centennial: toward a future anthropology.” Theory, Culture & Society 25(7/8):321–40.

- [7] Claude Lévi-Strauss: Tristes Tropiques, in English, translated by John Russell, 1961

- [8] Claude Levi-Strauss, Notes in an early work, often cited as an extreme example of androcentrism, even among leading anthropologists, “Contribution à l’étude de l’organisation sociale des Indiens Bororo” (1936) p. 283

- [9] Sayan Chattopahyay, noc18-hs31-Lecture 17-Structuralism: Claude Levi-Strauss, IIT Kanpur July 2018 @ youtube

- [10] Timeline of French ethnologists, via Wikidata and DBpedia