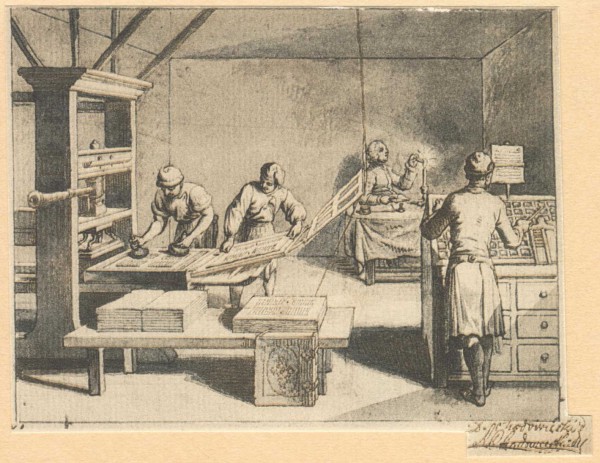

Early printing machine, by Johann Bernhard Basedow

On September 19, 1968, American physicist, inventor, and patent attorney Chester F. Carlson passed away. He is best known for having invented the process of electrophotography, which produced a dry copy rather than a wet copy, as was produced by the mimeograph process. Carlson’s process was subsequently renamed xerography, a term that literally means “dry writing.”

Chester Carlson – Early Years

Chester F. Carlson was the only child of Olof Adolph (* 1870; † 1932) and Ellen Josephine Carlson, née Hawkins (* 1870; † 1923). Due to the inability to work of his father, who suffered from arthritis and tuberculosis, the family lived in bitter poverty. In search of a healing climate, the Carlsons often moved, but without the hoped-for success. In San Bernardino, California, the family finally settled around 1912 and little Chester started school. Due to his poverty, the boy was an outsider at school who had little contact with his classmates. From the age of eight, Chester helped to support his family through small jobs. It is believed that when Chester Carlson was about ten years old, he created a newspaper called This and That, created by hand and circulated among his friends with a routing list. Young Carlson was also interested in printing technology, which he had got to know as a cleaning assistant in a local print shop. He published “The Amateur Chemist Press,” a magazine he produced on his own and offered on a subscription basis to his classmates who were interested in natural science, on a decommissioned, pedal-operated printing press. With this project, he realized how much work was required for printing reproduction, and for the first time he thought about simpler duplication methods. Chester Carlson attended Riverside Junior College and there also began as a chemistry major, switching to physics later on. In 1930, Carlson earned his Bachelor of Science degree in Physics from Caltech.

At Bell Labs

At Bell Telephone Laboratories in New York City, Carlson began working as a research engineer. For two years he lived in Brooklyn, first in the YMCA, then in a foreigners’ home and with his aunt Ruth in Passaic (New Jersey), always anxious to keep his cost of living as low as possible in order to repay his debts from his studies at CalTech. He finally moved to New York, where he shared a one-bedroom apartment with Lawrence Dummond, a reporter who worked for the Daily News at night. Carlson felt his work at Bell (sampling quality coal for telephone headphones) was a dead end. However, at Bell Labs, Chester Carlson noted more than 400 ideas and kept his enthusiasm for printing. Due to the economic crisis, his job at Bell was no longer secure and in the summer of 1933 he, like many other colleagues, was dismissed. This was a low point in his life. But Carlson did not give up, but asked all New York patent attorneys for work. After six weeks he found a new job and after one year changed to P. R. Mallory, a well-known manufacturer of electrical and electronic components.

A Modern Copy Machine

Many copies of texts and drawings were needed daily for the work in the patent department: The patent specifications were copied with a typewriter and carbon paper, the drawings of service companies were copied photographically. Carlson recognized the need for a simple office copier without complicated photographic procedures and finally concentrated his inventive efforts on solving this problem. During the 1930s, Chester Carlson began studying law to become an patent attorney. He had to copy books at the New York Public Library because he could not afford them. There, Carlson was inspired by an article by Hungarian physicist Pál Selényi in an obscure German scientific journal, that showed him a way to obtain his dream ‘copy’ machine. Carlson began experimenting and at first, his attempts resulted in explosions and really bad smells. The first preliminary patent application was filed in October 1937. Inspired by Selényi’s paper, Chester Carlson to use light to remove the static charge from a uniformly-ionized photoconductor. As no light would reflect from the black marks on the paper, those areas would remain charged on the photoconductor, and would therefore retain the fine powder. He could then transfer the powder to a fresh sheet of paper, resulting in a duplicate of the original.

Finally, a Patent

In 1938, Carlson and Otto Kornei (who had previously joined the experiments) prepared a zinc plate with a sulfur coating, darkened the room, rubbed the sulfur surface with a cotton handkerchief to apply an electrostatic charge, then laid the slide on the plate, exposing it to a bright, incandescent light. They removed the slide, sprinkled lycopodium powder to the sulfur surface, softly blew the excess away, and transferred the image to a sheet of wax paper. They heated the paper, softening the wax so the lycopodium would adhere to it, and had the world’s first xerographic copy. They repeated the experiment and Chester Carlson was astonished while Kornei was so disappointed that he discontinued his work on the problem. Also investors did not understand Carlson’s work while others did simply not believe in the product. Still, in 1942, the Patent Office issued Carlson’s patent on electrophotography.

From Electrophotography to Xerography

In 1945, Chester Carlson presented his ideas before the Battelle Memorial Institute in Columbus, Ohio with success. From then on, he was supported in his further reaseach and marketing. One year later, Battelle, Carlson, and the Haloid company signed the first agreement to license electrophotography for a commercial product. When Haloid intended to make public announcements about electrophotography to retain its claims to the technology, the term ‘electrophotography’ bothered them. In 1948, ten years to the day after that first microscope slide was copied, the Haloid Company made the first public announcement of xerography. The first device, the XeroX Model A Copier, became the first commercial photocopier. Unfortunately, the process was still manual and the machine was quite hard to use. Further, competitors on the market like Kodak and 3M began selling their own copying devices. Kodak’s Verifax device was also substantially more expensive and larger than Haloid’s.

The Xerox Corporation

The Rank Organisation also began investing and marketing the product. By 1958, Haloid was renamed to Haloid Xerox, accepting that xerography was now the company’s main line of business. The Xerox 914 model was probably the first device recognizable as a modern photocopier. It allowed an operator to place an original on a sheet of glass, press a button, and receive a copy on plain paper. Xerox 914 entered the market in 1959 and was very successful. Two years later, the company changed its name to Xerox Corporation.

Later Life

Until 1965, Carlson benefited directly from the boom in xerography. From the early 1960s, the value of Xerox shares rose up to fortyfold. He became exceptionally wealthy and received numerous honors, but maintained his modest lifestyle. He found in the distribution of his wealth a new task that would keep him busy for the rest of his life. He did everything himself, weighed each request personally, and donated large sums to racial integration, pacifist organizations, and the promotion of democracy. He promoted universities, schools, hospitals, libraries. For example, he established a research center for physical chemistry at CalTech and funded the research of parapsychologist Ian Stevenson on reincarnation, for which he donated a chair at the University of Virginia.

In the afternoon of September 15th, 1968, between two appointments in a cinema, he watched the English comedy “He Who Rides a Tiger“. After the end of the film, the usher wanted to wake the alleged sleeper, but Chester F. Carlson had died during the film at the age of 62.

Jennifer Dochstader and David Walsh, The Future of Digital Printing, [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Chester Carlson at Britannica

- [2] Chester Carlson at the Engineering and Technology Wiki

- [3] Static Pops Pictures onto Paper at Popular Science

- [4] Heavy Metal Madness: Making Copies from Carbon to Kinkos

- [5] Chester Carlson at Wikidata

- [6] Jennifer Dochstader and David Walsh, The Future of Digital Printing, Domino Digital Printing North America @ youtube

- [7] Owen, David (2004). Copies in Seconds: Chester Carlson and the birth of the Xerox machine. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- [8] Kearns, David T.; Nadler, David A. (1992). Prophets in the Dark: How Xerox reinvented itself and beat back the Japanese. HarperCollins.

- [9] David Owen, Copies in Seconds: How a lone inventor and an unknown company created the biggest communication breakthrough since Gutenberg—Chester Carlson and the birth of the Xerox Machine (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004)

- [10] Timeline of 20th century American inventors, via Wikidata and DBpedia