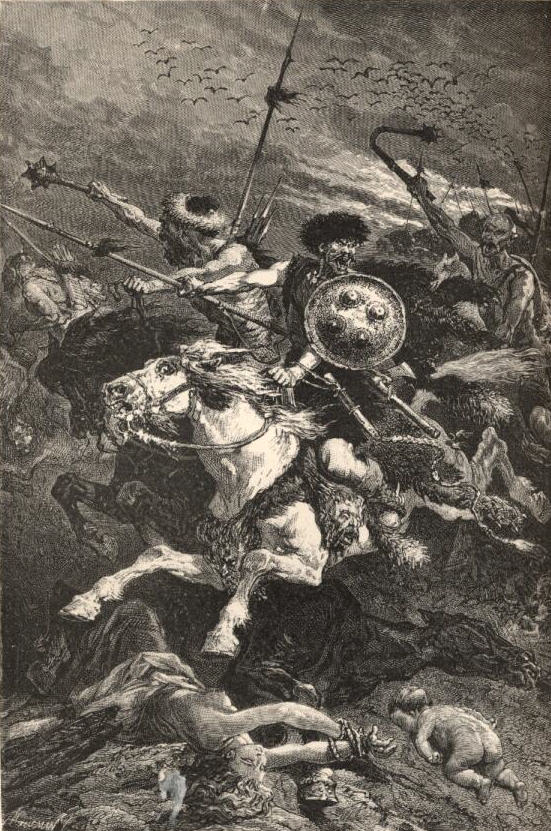

The Huns at the Battle of Chalons

by Alphonse de Neuville (1836–85)

On September 20, 451 AD, (or June 20, 451 according to other sources) the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains also referred to as the Battle of Chalons took place. A coalition led by the Roman general Flavius Aëtius and the Visigothic king Theodoric I against the Huns and their allies commanded by their leader Attila faced each other in a decisive battle that should decide the fate of Europe and the whole Western civilization…

The Huns and the Great Migration

Let’s face it, the Roman Empire, at least its western part, was almost at an end by the mid 5th century AD. There was turmoil and dissolution at every end. The eastern and the western part of the original empire already had separated a century ago. In 449 AD Rome had already given up Britain. Rome also was used to invasions by hords of barbarians and the time of the Great Migration was about to start. But, the Huns were rather special, compared to the Germanic tribes the Romans were used to fight against. The Huns were a group of nomadic people who first appeared in Europe from east of the Volga River, region of the earlier Scythians, with a migration intertwined with the Alans. Initially being near the Caspian Sea in 91 AD, the Huns migrated to the southeastern area of the Caucasus by about 150 AD and into Europe by 370 AD, where they succeeded to establish a vast Hunnic Empire. The Huns may have been the main stimulus for the Great Migration. But, at least they a contributing factor in the collapse of the western Roman Empire.

“They made their foes flee in horror because their swarthy aspect was fearful, and they had, if I may call it so, a sort of shapeless lump, not a head, with pin-holes rather than eyes. Their hardihood is evident in their wild appearance, and they are beings who are cruel to their children on the very day they are born. For they cut the cheeks of the males with a sword, so that before they receive the nourishment of milk they must learn to endure wounds. Hence they grow old beardless and their young men are without comeliness, because a face furrowed by the sword spoils by its scars the natural beauty of a beard. They are short in stature, quick in bodily movement, alert horsemen, broad shouldered, ready in the use of bow and arrow, and have firm-set necks which are ever erect in pride. Though they live in the form of men, they have the cruelty of wild beasts.” (Jordanes, from The Goths)

Attacking the Roman Empire

In 370 AD the Huns crossed the Volga river and attacked the Alans, whom they subjugated. However, in 395 the Huns began their first large-scale attack on the East Roman Empire as they attacked in Thrace, overran Armenia, and pillaged Cappadocia. They entered parts of Syria, threatened Antioch, and swarmed through the province of Euphratesia, and in 398 they left again to attack the neighbored Sassanid Empire. In the early 5th century, the brothers Attila and Bleda ruled together the Huns, but each king had his own territory and people under him. Never did two Hun kings rule the same territory. They forced the Eastern Roman Empire to sign the Treaty of Margus, giving the Huns trade rights and an annual tribute from the Romans. With their southern border protected by the terms of this treaty, the Huns could turn their full attention to the further subjugation of tribes to the east. When Bleda died in 445, Attila became the sole ruler of the Hun Empire.

Claiming the Western Roman Empire as Dowry

Throughout their raids on the Eastern Roman Empire, the Huns had maintained good relations with the Western Empire, this was due in no small part to their friendship with Flavius Aetius, a powerful Roman general (sometimes even referred to as the de facto ruler of the Western Empire) who in his youth had spent some time as a hostage with the Huns. However, this all changed in 450 when Honoria, sister of the Western Roman Emperor Valentinian III, sent Attila a ring and requested his help to escape her betrothal to a senator. Although it is not known whether Honoria intended this as a proposal of marriage to Attila, that is how the Hun King interpreted it. He claimed half the Western Roman Empire as dowry. To add to the failing relations, a dispute arose between Attila and Aetius about the rightful heir to the kingdom of the Salian Franks.

The Battle at the Catalaunian Plains

In 451, Attila’s forces entered Gaul, with his army recruiting from the Franks, Goths and Burgundian tribes en route. Once in Gaul, the Huns first attacked Metz, then his armies continued westwards, passing both Paris and Troyes to lay siege to Orléans. Aetius was given the duty of relieving Orléans by Emperor Valentinian III. Bolstered by Frankish and Visigothic troops (under King Theodoric), Aetius’ own Roman army with 20.000 men met the Huns at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains. The name Catalaunian Plains (Latin Campi Catalauni) comes from the Gallic tribe of the Catalauns, who settled in the region where the battle took place. The identification of the battlefield is controversial. Thus, to this day, it has not been possible to establish with certainty where exactly the battle took place. For a long time, the plain near Châlons-en-Champagne was accepted as the site of the battle. But since it is reported that Attila retreated from Orléans to the east, it seems more likely that the battle was fought somewhere on the plain between Châlons-en-Champagne and Troyes (today’s northeast France), probably closer to Troyes. It is known that the battlefield was dominated by a wide plain. It was bounded to the north by a river, probably the Marne, and to the south by a number of unconnected forests. In the north a hill rose before the river.

The Fighting

As Aetius realized that his men were heavily outnumbered, he made an alliance with the Visigoths, under Theodoric, the Franks, and the Burgundian tribes, forming a coalition army of 50,000 men. On the other side, the Huns’ army was reinforced with the Ostrogoths, Alans and other Germanic tribes, totaling 65,000 soldiers. In accordance to Hunnic customs, Attila had his diviners examine the entrails of a sacrifice the morning before battle. They foretold disaster would befall the Huns and one of the enemy leaders would be killed. At the risk of his own life and hoping for Aëtius to die, Attila at last gave the orders for combat, but delayed until the ninth hour so the impending sunset would help his troops to flee the battlefield in case of defeat. The fighting was ferocious and lasted for several hours until nightfall; the Visigoth chief, Theodoric, was killed in battle during a charge at the Huns camp, but his son Thorismund took command. When the sun came up the following morning, Attila’s army had been routed and headed southeast, as thousands of Hunnic, Germanic, and Roman soldiers lay dead in the battlefield. The Huns had been defeated for the first time in many years. This battle, especially since Edward Gibbon addressed it in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire has been considered by many historians to be one of the most important battles of Late Antiquity, at least in the Latin-speaking world.[5]

“Attila’s retreat across the Rhine confessed the last victory which was achieved in the name of the Western Roman Empire.”

(Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire)

A Decisive Battle for the World

Another reason why historians argued about the battle as one of the most decisive battles for the world as we know it today is the fact, that it was the last major battle of a Christian Rome against a powerful Pagan enemy. From the viewpoint of the contemporary Christian historians, Christianity itself was at the stake. The following year, Attila renewed his claims to Honoria and territory in the Western Roman Empire. Leading his troops across the Alps and into Northern Italy, he conquered the cities of Aquileia, Vicetia, Verona, Brixia, Bergomum and Milan. Finally, at the very gates of Rome, he turned his army back only after negotiating with the pope. A year later, the Hunnic Empire broke down and soon afterwards the Huns disappear from contemporary records. BTW, the refugees from Aquilea, Padua and Treviso fled from the Huns to the lagoons of the Adriatic sea and established a settlement that should later become Venice. But this is already another story…

Clifford Ando | The Long Defeat: The Fall of the Roman Empire, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Battle at the Catalaunian Fields at The Art of Battle

- [2] The Battle at Chalons at militaryhistory about.com

- [3] The Battle of Chalons at historynet.com

- [4] Sir Edward Creasy’s The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World: from Marathon to Waterloo, at Gutenberg.org

- [5] Edward Gibbon and the Science of History, SciHi Blog

- [6] The Battle at the Catalaunian Plains at Wikidata

- [7] Clifford Ando | The Long Defeat: The Fall of the Roman Empire, 2013, The Oriental Institute @ youtube

- [8] Whately, Conor (2013). “Jordanes, the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, and Constantinople”. Dialogues d’Historie Ancienne. 8 (1): 65–78.

- [9] Kim, Hyun Jin (2013). The Huns, Rome, and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–74.

- [10] Hughes, Ian (2012). Aetius: Attila’s Nemesis. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military

- [11] Kim, Hyun Jin (2015). “‘Herodotean’ allusions in Late Antiquity: Priscus, Jordanes, and the Huns”. Byzantion (85).

- [12] Timeline of Battles of the Roman Empire, via DBpedia and Wikidata