The East Indiaman Royal George, 1779. Royal George was one of the five East Indiamen the Spanish fleet captured in 1780.

On December 31, 1600, the British East India Company (EIC) received a Royal Charter from Queen Elizabeth making it the oldest among several similarly formed European East India Companies pursuing trade with the East Indies.

“The East India Company established a monopoly over the production of opium, shortly after taking over Bengal.”

– Robert Trout [11]

The Foundation of the British East India Company

Already 12 years before, the Spanish Armada was defeated and merchants turned to the Queen, asking for permission to sail to the Indian Ocean, which was granted. Some smaller companies formed, but several ships got lost on the sea. On 22 September 1599, a group of merchants met and stated their intention “to venture in the pretended voyage to the East Indies (the which it may please the Lord to prosper), and the sums that they will adventure”, committing £30,133. Two days later, “the Adventurers” reconvened and resolved to apply to the Queen for support of the project. Although their first attempt had not been completely successful, they nonetheless sought the Queen’s unofficial approval to continue. On 31 December 1600, Queen Elizabeth I granted a Royal Charter to ‘Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading with the East Indies‘ and the first voyages took place one year after.[4]

The First Voyage

Sir James Lancaster commanded the first East India Company voyage in 1601 aboard the Red Dragon. After capturing a rich 1,200 ton Portuguese Carrack in the Malacca Straits the trade from the booty enabled the voyagers to set up two “factories” – one at Bantam on Java and another in the Moluccas (Spice Islands) before leaving. English traders frequently engaged in hostilities with their Dutch and Portuguese counterparts in the Indian Ocean. The company achieved a major victory over the Portuguese in the Battle of Swally in 1612, at Suvali in Surat. The company decided to explore the feasibility of gaining a territorial foothold in mainland India, with official sanction from both Britain and the Mughal Empire, and requested that the Crown launch a diplomatic mission. To succeed against the Dutch and Portuguese on the market, the British realized, that they needed to gain territorial foothold at India’s mainland. Also, James I instructed Sir Thomas Roe to meet Mughal Emperor Nuruddin Salim Jahangir in order to arrange exclusive trading rights and the possibility of building factories in Surat and the surrounding area, which was successful.

A Company with Extraordinary Powers

As the company expanded, they were able to establish several trading posts and numerous factories in India. In the 1630s, the Mughal emperor extended his hospitality to the company, but competition with the Dutch grew as well, which resulted in the Anglo-Dutch Wars. Within the first two decades of the 17th century, the Dutch East India Company or Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, (VOC) was the wealthiest commercial operation in the world with 50,000 employees worldwide and a private fleet of 200 ships. It specialised in the spice trade and gave its shareholders 40% annual dividend. The British East India Company was fiercely competitive with the Dutch and French throughout the 17th and 18th centuries over spices from the Spice Islands. Spices, at the time, could only be found on these islands, such as pepper, ginger, nutmeg, cloves and cinnamon could bring profits as high as 400 percent from one voyage. The tension was so high between the Dutch and the British East Indies Trading Companies that it escalated into at least four Anglo-Dutch Wars between them. King Charles II was motivated to strengthen the power of the EIC and provisioned the EIC with the rights to autonomous territorial acquisitions, to mint money, to command fortresses and troops and form alliances, to make war and peace, and to exercise both civil and criminal jurisdiction over the acquired areas.

Pirate Henry Every – His successful raids threatened the English trading in India

Pirates

But not only the Dutch were a danger to the EIC, in 1695, the English pirate Henry Every was able to raid the treasure-laden Ganj-i-Sawai, which became known as the richest ship ever taken by pirates. It is assumed that the loot totals between £325,000 and £600,000, including 500,000 gold and silver pieces. The English government and the Indian emperor were furious about the loss and angry Mughals threatened to put an end to all English trading in India. On 12 October 1695, Sir John Gayer, then-governor of Bombay and president of the East India Company, sent a letter to the Lords of Trade, writing:

“It is certain the Pyrates, which these People affirm were all English, did do very barbarously by the People of the Ganj-i-sawai and Abdul Gofor’s Ship, to make them confess where their Money was, and there happened to be a great Umbraws Wife (as Wee hear) related to the King, returning from her Pilgrimage to Mecha, in her old age. She they abused very much, and forced severall other Women, which Caused one person of Quality, his Wife and Nurse, to kill themselves to prevent the Husbands seing them (and their being) ravished.”

East India House in London

The Industrial Revolution

Meanwhile, the company started to develop a lobby in the English parliament and the company’s power grew. By 1720, 15% of British imports were from India, almost all passing through the company. With the ‘arrival’ of the Industrial Revolution, the EIC became the single largest player in the British global market and the British culture, economy and high living standards had a profound influence on overseas trade.

American Revolution

Through the years, the company had to fight and compete in order to expand its trade positions and military power in India. But even though the company became increasingly bold and ambitious in putting down resisting states, it faced financial troubles as well. In 1773, the Tea Act was passed, which gave the Company greater autonomy in running its trade in the American colonies, and allowed it an exemption from tea import duties which its colonial competitors were required to pay. The arrival of tax-exempt Company tea, triggered the Boston Tea Party in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, one of the major events leading up to the American Revolution.

Company painting depicting an official of the East India Company, c. 1760

Indian Revolution

The company’s efforts to administer India served as a model for British civil administration, especially in the 19th century. After the company lost its trading monopoly in 1833, it became a pure trading company again. In 1858, the company lost its administrative function to the British government after its Indian soldiers mutinied. Because of the Indian Uprising in 1857, the company lost all of its administrative powers and on 1 January, 1874 an Act came into effect dissolving the company in the summer of the same year. Then British India became a formal crown colony. In the following years, the company’s possessions were nationalized by the Crown. The company still managed the tea trade on behalf of the government, especially after St. Helena.

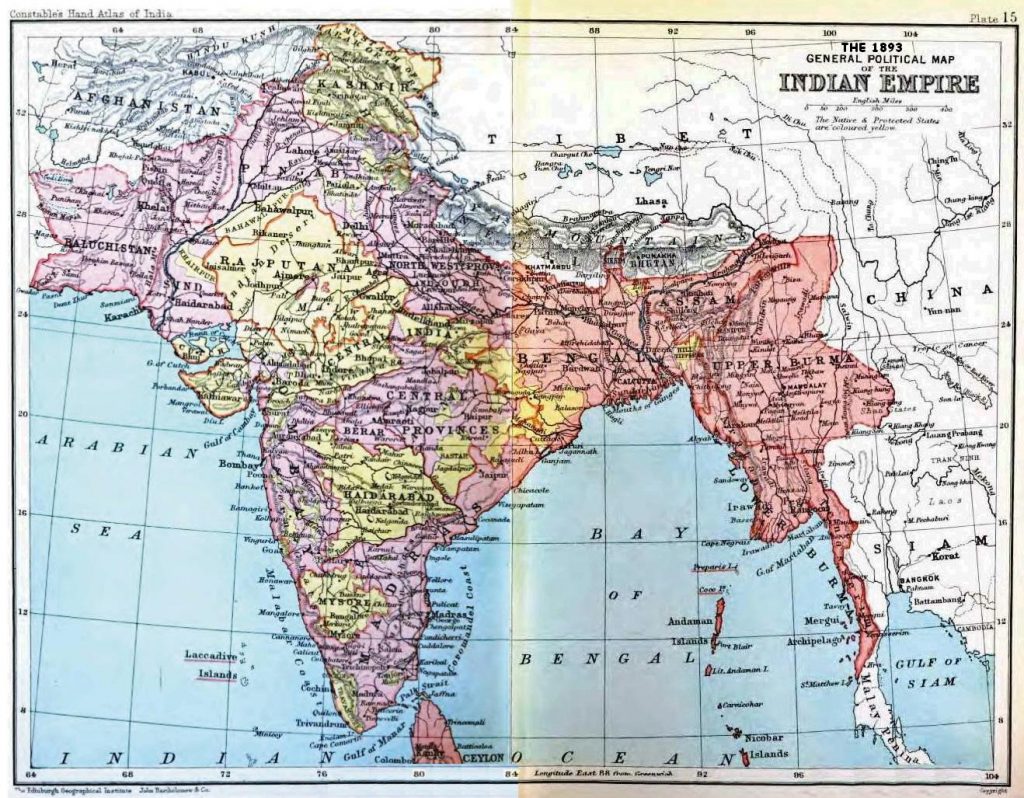

Political Map of the Indian Empire, 1893″ from Constable’s Hand Atlas of India, London: Archibald Constable and Sons, 1893

However, the EIC had a large effect on the Indian culture and global trade. The East India Company was the first company to record the Chinese usage of orange-flavoured tea in which it led to the development of Earl Grey tea and the British trade with India played a key role in introducing English as an official language in India.

John McAleer, Britain’s global trade in the Great Days of Sail, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] East India Company at BBC

- [2] Baladouni, Vahe (1983). Accounting in the Early Years of the East India Company

- [3] History and Politics: East India Company

- [4] The Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I, SciHi Blog

- [5] The East India Company at Wikidata

- [6] Charter Granted by Queen Elizabeth to the East India Company

- [7] Nick Robins, “The world’s first multinational”, 13 December 2004, New Statesman

- [8] “The East India Company – a corporate route to Europe” on BBC Radio 4‘s In Our Time featuring Huw Bowen, Linda Colley and Maria Misra

- [9] Timeline of the British East India Company, via DBpedia and Wikidata

- [10] John McAleer, Britain’s global trade in the Great Days of Sail, Gresham College @ youtube

- [11] East India Company at quotemaster.org

COWBOYS & INDIANS

India was at one time almost certainly the richest nation in the world, with stocks of gold, silver and precious gems worthy of fable and legend. The British East India Company which was eventually led by one of the Rothschilds, was unquestionably the greatest criminal enterprise in the history of the world, and the vehicle used to loot India to the bones.

Sassoon ben Salih was the chief treasurer to the pashas of Baghdad.[10]

Exposed in an immense fraud in the early 1800s that must have involved hundreds of billions in today’s dollars, he was lucky to escape with his life (and the money). He and his two sons David and Joseph fled to India where they teamed up with one of the Rothschilds and hatched their infernal plan to force Indian peasants to grow opium for sale in China.[11]

From the early days, they already had the young Queen Victoria firmly in their grasp. She not only supported their efforts to the extent of allocating the British military as the Jews’ enforcers of the opium, giving David Sassoon the exclusive franchise for selling opium in all of China, seizing Hong Kong for his distribution base and giving him the charter to form the HSBC. To say that the British Royal Family profited heavily from this personally, would be an understatement of some magnitude. This is where we will begin our story.

From their wholesale looting of India and the thefts from Iraq, followed by growing and selling of opium in China, Rothschild and Sassoon were reliably estimated to have accumulated wealth of more than $5 billion each, by 1835. Actually, the calculated estimates I have seen were of $6 billion and $7 billion,[12]

and these were my estimates as well. I reduced this to $5 billion to be conservative, but the totals are still staggering. $5 billion accumulated at only 5% for the intervening 185 years, accumulates to a total in 2022, of more than $40 trillion each for Rothschild and Sassoon. And there were at least a dozen or more Jewish banking families that were not so very far behind Rothschild and Sassoon, as well as many dozens more that were very wealthy but not in this same league. That $40 trillion may seem shocking and too fantastic to be real, but reserve your judgment until the end. As you will see, that $40 trillion is almost irrelevant in the overall picture.

[10] SASSOON: By: Joseph Jacobs, Goodman Lipkind, J. Hyams

https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/13218-sassoon

[11] Precursor To The Global Crime Syndicate: The 19th-Century Opium Trade

https://www.winterwatch.net/2022/08/precursor-to-the-global-crime-syndicate-the-19th-century-opium-trade/

[12] Currency Wars, Song Hongbing

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/18618477-currency-wars