Arthur Holmes (1890-1965)

On January 14, 1890, British geologist Arthur Holmes was born. Holmes pioneered the use of radiometric dating of minerals and was the first earth scientist to grasp the mechanical and thermal implications of mantle convection, which led eventually to the acceptance of plate tectonics.

“There are few problems more fascinating than those that are bound up with the bold question: How old is the Earth? With insatiable curiosity men have been trying for thousands of years to penetrate the carefully guarded secret.”

– Arthur Holmes, as quoted in [14]

Arthur Holmes – Early Years

Arthur Holmes was born in Hepburn, near Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the son of David Holmes, a cabinet-maker, and his wife, Emily Dickinson. As a child he lived in Low Fell, Gateshead and attended the Gateshead Higher Grade School. One of his teachers, Mr.McIntosh, introduced his pupils to the Popular Lectures and Addresses of Lord Kelvin [8] as well as with the work of the Swiss geologist Edward Suess,[9] whose first volume of his great synthesis, The Face of the Earth, had recently been translated into English. Holmes later remarked how the inspirational Mr. McIntosh and these two works were largely responsible for the direction his life took.[4] At 17, he enrolled to study physics at the Royal College of Science (now Imperial College London), but took a course in geology in his second year which settled his future, against the advice of his tutors. Surviving on a small scholarship was difficult and after graduation in 1910 he took a job prospecting for minerals in Mozambique. Unfortunately, he became so ill with malaria that a notice of his death was posted home. However he recovered enough to catch the boat home and became a demonstrator at Imperial College in 1912.

A Pioneer in Geochronology

Radioactivity had been discovered in 1896 and was causing much excitement By 1904, Ernest Rutherford had determined the first radiometric date, utilizing the discovery that helium was generated in the decay process.[11] Unfortunately, owing to the problem of helium leakage, these early dates were only minimum values, so Holmes decided to combine his interest in physics and geology in the search for an alternative technique.[4] Holmes performed the first accurate uranium-lead radiometric dating specifically designed to measure the age of a rock already while an undergraduate in London, assigning an age of 370 million years to a Devonian rock from Norway, improving on the work of Bertram Boltwood, the American pioneer of radiochemistry, who published nothing more on the subject. This result was published in 1911, a year after his graduation.

The Age of the Earth

In 1913 Holmes published his famous book The Age of the Earth, in which he argued strongly for radioactive methods compared with methods based on geological sedimentation or cooling of the earth. Many people still clung to Lord Kelvin‘s calculations of less than 100 million years, while Holmes estimated the oldest Archean rocks to be 1,600 million years, but did not speculate about the Earth’s age [8]. By this time the discovery of isotopes had complicated the calculations and he spent the next years grappling with these. His promotion of the theory over the next decades he earned the nickname of Father of modern geochronology. In 1917, at the age of 27 he received his doctorate of science from Imperial College as well. In 1920, Holmes joined an oil company in Burma as chief geologist. The company failed, and he returned to England penniless in 1924, but was appointed to the newly created post of reader in geology at Durham University. By 1927 he had revised his estimations to 3,000 million years and in the 1940s to 4,500±100 million years, based on measurements of the relative abundance of uranium isotopes by Alfred O. C. Nier. The general method is now known as the Holmes-Houterman model after Fritz Houtermans who published in the same year, 1946.

Continental Drift

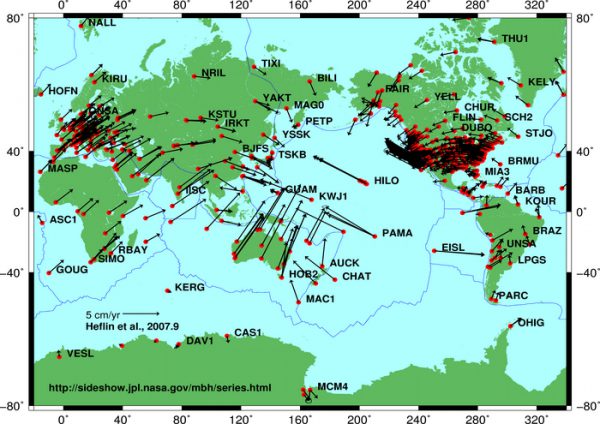

Scientists were debating the validity and possibility of continental drift promoted by Alfred Wegener,[10] when Holmes focussed on this problem at a time when it was deeply unfashionable with his more conservative peers. The main issue raised by many scientists is the mechanism by which the continents could move. Holmes major contribution was the hypothesis that the radioactive decay occurring in the mantle of Earth would generate heat, and thereby convection currents that would be the means by which the continents could move.[2] His Principles of Physical Geology (1944), which became a standard textbook in the UK and elsewhere, ended with a chapter on continental drift [3]. Part of the model was the origin of the seafloor spreading concept. Holmes was not a dogmatic adherent of Drift who was searching for a solution to the ‘mechanism’ problem. Rather, he was a sound geologist, who believed that there were enormous radioactive forces present in the earth’s interior which simply had to escape to the earth’s surface, and who recognized that these provided a solution to the ‘mechanism’ problem faced by drift.[2]

Plate motion based on Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite data from NASA JPL. The vectors show direction and magnitude of motion.

Later Years

In 1942 his achievements were recognized, when he became a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the following year he was appointed to the Regius Professor of Geology at the University of Edinburgh, which post he held until retirement in 1956. It was there, despite his declining health, that he completed some of his most important work on the age of the Earth, the geological time scale, the Precambrian, and the geology of Africa.[4] Holmes was awarded both the Wollaston Medal and the Penrose Medal in 1956, as well as the Vetlesen Prize in 1964, but at no presentation was his work on continental drift ever mentioned. [4] Arthur Holmes died in Putney, London on 20 September 1965, at the age of 75. The Arthur Holmes Medal of the European Geosciences Union is named after him.

PHYS 152 Lecture 41 Radiometric Dating April 24, 2017, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Arthur Holmes, People and Discoveries, at pbs.org

- [2] Earth 520: Plate Tectonics and People, Rock Star: Arthur Holmes, at Penn State University

- [3] Principles of Physical Geology 1944, Thomas Nelson & Sons, 2nd edition 1965, 3rd edition (with Doris Holmes) 1978, 4th edition (with Donald Duff) 1993.

- [4] Lewis, Cherry L. E., Arthur Holmes: An Ingenious Geoscientist, March 2002, GSA Today

- [5] Holmes, Arthur (1913), The Age of the Earth, London: Harper, digitized from archive.org

- [6] Alfred Wegener and the Continental Drift, SciHi Blog, January 6, 2013.

- [7] Arthur Holmes at Wikidata

- [8] Lord Kelvin and the Analysis of Thermodynamics, SciHi Blog, Dec 17, 2015.

- [9] Eduard Suess and the Study of Tectonics, SciHi Blog

- [10] Alfred Wegener and the Continental Drift, SciHi blog

- [11] Ernest Rutherford Discovers the Nucleus, SciHi Blog

- [12] PHYS 152 Lecture 41 Radiometric Dating April 24, 2017, UC PHYS 151/152/251/252 General/College Physics @ youtube

- [13] Dunham, K. C. (1966). “Arthur Holmes 1890-1965”. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 12: 290–310.

- [14] Arthur Holmes quotes,@ libquotes

- [15] Timeline for Arthur Holmes, via Wikidata