![Arthur C. Clarke in February 1965, on one of the sets of 2001: A Space Odyssey, picture: ITU Pictures [CC BY 2.0]](http://scihi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Arthur_C._Clarke_1965-650x437.jpg?_t=1576522452)

Arthur C. Clarke (1917-1982) in February 1965, on one of the sets of 2001: A Space Odyssey, picture: ITU Pictures [CC BY 2.0]

On December 16, 1917, British science fiction writer, science writer and futurist, inventor, undersea explorer, and television series host Sir Arthur C. Clarke was born. He is probably best known for co-authoring the screenplay of the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, one of the most influential films of all time. Clarke’s science and science fiction writings earned him the moniker “Prophet of the Space Age” His science fiction earned him a number of Hugo and Nebula awards, which along with a large readership made him one of the towering figures of science fiction.

“If we have learned one thing from the history of invention and discovery, it is that, in the long run — and often in the short one — the most daring prophecies seem laughably conservative.”

– Arthur C. Clarke, The Exploration of Space (1951)

An early Interest into Science Fiction

Clarke was born in Minehead, Somerset, England, and grew up in nearby Bishops Lydeard. As a boy, he lived on a farm, where he enjoyed stargazing, fossil collecting, and reading American science fiction pulp magazines. He received his secondary education at Huish Grammar school in Taunton. Some of his early influences included dinosaur cigarette cards, which led to an enthusiasm for fossils starting about 1925. Clarke attributed his interest in science fiction to reading three items: the November 1928 issue of Amazing Stories in 1929; Last and First Men by Olaf Stapledon in 1930; and The Conquest of Space by David Lasser in 1931.

Second World War and University Education

In his teens, he joined the Junior Astronomical Association and contributed to Urania, the society’s journal, which was edited in Glasgow by Marion Eadie. Because Clarke was initially denied the opportunity to study for financial reasons, he initially worked as an auditor. As early as the late 1930s, he wrote stories inspired by the science fiction magazines of his youth. He worked as a government auditor from 1936 to 1941. From 1941 to 1946 Clarke served in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War, where he worked as a radar specialist for the Ground Controlled Approach. After the war he studied mathematics and physics at King’s College London, where he graduated in 1948. Clarke was a participant in the world’s first science fiction convention in 1937. Already in 1934, interested in the possibilities that space could offer mankind, he became a member of the British Interplanetary Society (BIS), a small advanced group that advocated the development of rocketry and human space exploration.

Geostationary Satellites

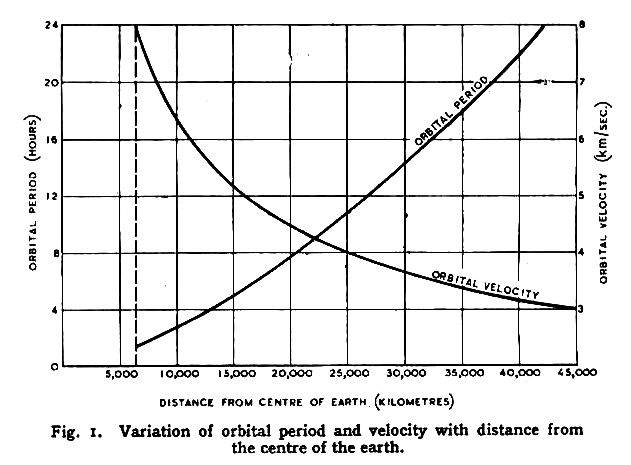

Clarke contributed to the popularity of the idea that geostationary satellites would be ideal telecommunications relays. He first described this in a letter to the editor of Wireless World in February 1945 and elaborated on the concept in a paper titled Extra-Terrestrial Relays – Can Rocket Stations Give Worldwide Radio Coverage?, published in Wireless World in October 1945. The geostationary orbit is now sometimes known as the Clarke Orbit or the Clarke Belt in his honour. However, the idea of communicating via satellites in geostationary orbit itself had been described earlier. For example, the concept of geostationary satellites was described in Hermann Oberth‘s 1923 book Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (The Rocket into Interplanetary Space),[3] and then the idea of radio communication by means of those satellites in Herman Potočnik‘s 1928 book Das Problem der Befahrung des Weltraums – der Raketen-Motor (The Problem of Space Travel — The Rocket Motor). In 1964 Clarke experienced how this idea was put into practice with Syncom 3.

Considerations about the orbital speed of a satellite depending on the orbit height (1945)

Arthur C. Clarke’s Science Fiction

“One of the biggest roles of science fiction is to prepare people to accept the future without pain and to encourage a flexibility of mind. Politicians should read science fiction, not westerns and detective stories.”

– Arthur C. Clarke, as quoted in [9]

Since 1951 Clarke was a freelance writer. Clarke already published early works in some fanzines at the end of the 1930s. His first commercial publication was the short story Loophole, which appeared in 1946 in the magazine Astounding Science Fiction. In the short story Technical Error, which appeared in 1950 under the title The Reversed Man in the magazine Thrilling Wonder Stories, he described how an employee of a power plant working with superconducting materials is “twisted sideways”. In the 1950s, Clarke was instrumental in showing the sea and the maritime in the futuristic novel (e.g. in Dolphin Island) and was one of the first divers out of sheer hobby. The Ghost from the Grand Banks is about the attempt to lift the Titanic. The idea of aquaculture, the systematic “farming” of the oceans, can be traced back to his work.His first nonfiction books were Interplanetary Flight (1950) and The Exploration of Space (1951). His first novels were routine stories of space exploration: Prelude to Space (1951), about the first flight to the Moon; The Sands of Mars (1951), about the colonization of that planet; and Islands in the Sky (1952), set on a space station.[2] In the 1950s Clarke wrote two short stories that became science fiction classics. In “The Nine Billion Names of God” (1953), a Tibetan monastery buys a computer to finish its centuries-long task of compiling the possible names of God. In the Hugo Award-winning “The Star” (1955), an expedition to a distant planet finds the ruins of a civilization that was destroyed when its star went supernova. A Jesuit priest on the expedition has his faith tested when he discovers that the supernova was the Star of Bethlehem.[2]

Childhood’s End and 2001: Space Odyssey

In the early novel Childhood’s End (1953), Clarke developed the idea of an all-encompassing and overpowering power or intelligence that permeates and influences the universe. As humanity is about to make its first flights into space, the alien Overlords arrive in gigantic spaceships to foster humanity’s union with the Overmind as a galaxy-wide intelligence. Decades after humans begin to develop psychic powers, merge into a group intelligence, and, as humanity’s last generation, finally join with the Overmind. Clarke would return to the themes of first contact and evolutionary leaps throughout his entire career. The novel is also strongly influenced by Clarke’s preoccupation with the supernatural. However, his most famous work is probably 2001: Space Odyssey. The novel is based on the screenplay for the 1968 film of the same name, which was written together with Stanley Kubrick and is based in part on several short stories by Clarke, including The Sentinel from 1948.[1] At the end of the second millennium, men set out to conquer the solar system. One day they will set out to conquer the stars. What will they find there? Their equals or their masters? This novel tries to answer this question. The three follow-up novels were also successful, but less than the original work. 2001: A Space Odyssey is often cited by film critics and historians as one of the greatest films of all time.

Further Literary Works

“It is vital to remember that information — in the sense of raw data — is not knowledge, that knowledge is not wisdom, and that wisdom is not foresight. But information is the first essential step to all of these.”

– Arthur C. Clarke, as quoted in [10]

A further major work of Arthur C. Clarke is the four-volume Rama cycle, the first part of which Rendezvous with Rama was published in 1973. The subsequent volumes, which were produced in collaboration with Gentry Lee, were published from 1989 to 1993. In this work, Clarke once again links the theme “Intruder into the Solar System” with the topos of the overpowering extraterrestrial intelligence. The trilogy A Time’s Odyssey (Guardian Cycle), published between 2004 and 2007 in collaboration with Stephen Baxter, also takes up the motif of extraterrestrial intelligence. Clarke’s work also contains humorous elements. In the short story collection Tales from the White Hart, published in 1957, scientific findings are applied in a seemingly logical way, but with absurd, sometimes catastrophic consequences. Clarke’s work had a formative influence on the genre of science fiction. Many subsequent authors cite him as a role model. He was one of the scientific and technical visionaries of the genre. His novels and stories are marked by technical achievements and the reaching for the stars. With his strong scientific-technical orientation, Clarke’s fiction work belongs to the subgenre of hard science fiction. The possibilities of human evolution also occupied Clarke time and again.

Clarke’s Laws

In his essay Profile of the Future, published for the first time in 1962, he argues that predictions of the future often suffer from a lack of courage and imagination, and that predictions are therefore often too pessimistic rather than too optimistic. In this context, he established the first of three “Clark’s Laws“, which today are among the most cited basic rules of science fiction.

- If a respected but elderly scientist claims that something is possible, he is right with a probability bordering on certainty. If he claims that something is impossible, he is most likely wrong.

- The only way to find the limits of what is possible is to push a little beyond them into the impossible.

- Any sufficiently advanced technology cannot be distinguished from magic.

Of these three “laws”, the third in particular – not only within science fiction literature – has achieved the character of a proverb. Thus the three Clark laws for the genre are as important as the three robot laws of Isaac Asimov.[4]

Further Predictions

“I’m sure the universe is full of intelligent life. It’s just been too intelligent to come here.”

– Arthur C. Clarke

Many of Clarkes works are based on current scientific findings and applications. They are set in a not-so-distant future and describe technology that is already possible, or at least conceivable, from today’s perspective. Typical topics are the exploration or colonization of the moon or other planets of the solar system. In addition, there are works which are set in a distant future or which deal with technical developments that far exceed today’s possibilities. While some of his own predictions, such as manned space flight and the exploration and colonization of other celestial bodies, were too optimistic in retrospect, he was quite precise with other predictions. As early as 1964, he described today’s Internet quite precisely. Clarke was not the first to describe the possibility of a space elevator, but his novel The Fountains of Paradise (1979) made sure that this concept was received by a broad public for the first time.

Last Years

Clarke was named Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1989 before being knighted as Knight Bachelor in 2000 in recognition of his literary and scientific achievements, with the addition of the name “Sir”. In 1988 he was diagnosed with polio, so that he later had to use a wheelchair. The tsunami of 26 December 2004 destroyed his diving school near Hikkaduwa on the southwest coast of Sri Lanka; it was rebuilt shortly afterwards.

Arthur C. Clarke died in March 2008 in a hospital in Sri Lanka, where he was treated for respiratory problems.

One day, a computer will fit on a desk (1974) | RetroFocus [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Breaking New Grounds in Cinematography – Stanley Kubrick, SciHi Blog

- [2] Arthur C. Clarke, British author and scientist, at Britannica online

- [3] Hermann Oberth’s Dream of Space Travel, SciHi Blog

- [4] Isaac Asimov and the Three Laws of Robotics, SciHi Blog

- [5] Works by or about Arthur C. Clarke at Internet Archive

- [6] Arthur C. Clarke at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- [7] Arthur C. Clarke at Wikidata

- [8] “Sir Arthur C Clarke”. The Telegraph. 19 March 2008.

- [9] Jerome Agel, The Making of Kubrick’s 2001 (1970)

- [10] One day, a computer will fit on a desk (1974) | RetroFocus, ABC News In-depth @ youtube

- [11] “Humanity will survive information deluge — Sir Arthur C Clarke” in OneWorld South Asia (5 December 2003)

- [12] Timeline for Arthur C. Clarke, via Wikidata