Antonie van Leeuwenhoek’s microscopes by Henry Baker

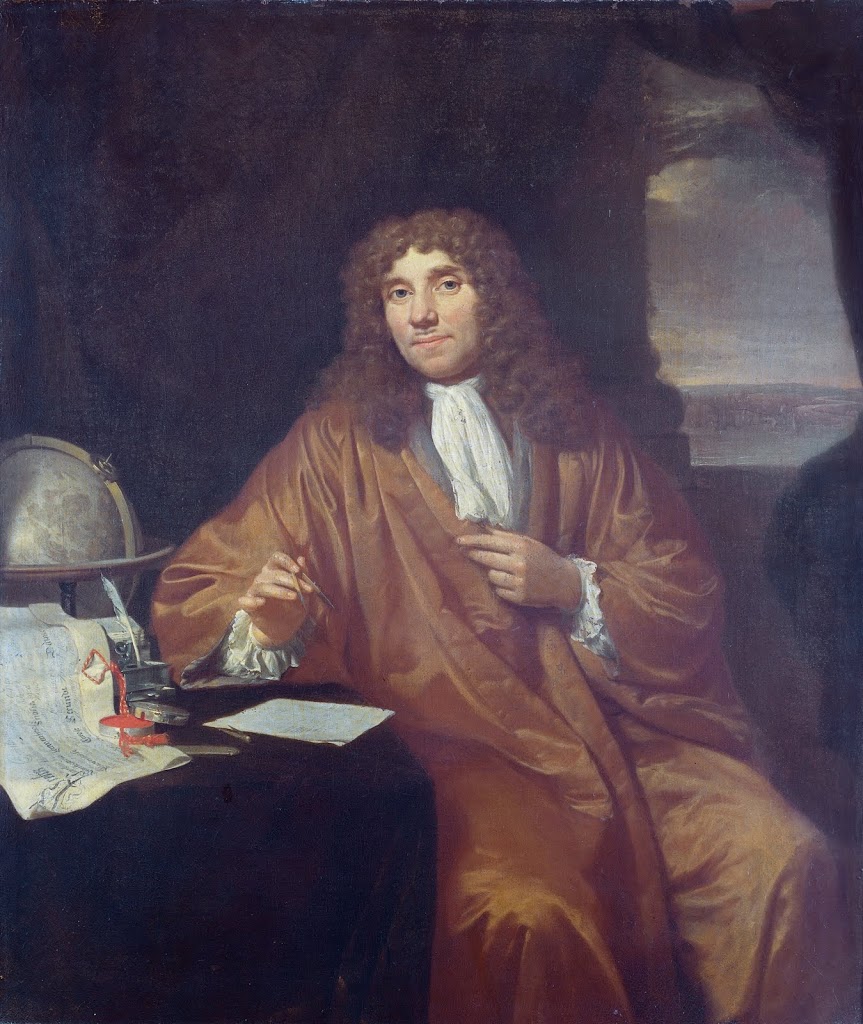

On October 24, 1632, the Dutch tradesman and scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, the inventor of the microscope, was born. He is commonly known as “the Father of Microbiology“, and considered to be the first microbiologist.

“Please bear in mind that my observations and thoughts are the outcome of my own unaided impulse and curiosity alone; for, besides myself, in our town there be no philosophers who practice this art, so pray, take not amiss my poor pen and the liberty I here take in setting down my random notions.”

– Antonie van Leewenhoek

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek – First Steps

That Van Leeuwenhoek made some of the most significant discoveries in the history of biology is rather surprising. Born in 1632, the son of a basket maker was not so fortunate to receive higher education or even a university degree. At the age of 16, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek began his apprenticeship with a cloth merchant in Amsterdam as bookkeeper and cashier. What the young Van Leeuwenhoek considered to be a quite miserable situation soon changed to be highly interesting. There he saw the first version of the microscope, a magnifying glass attached to a small stand, which was commonly used by cloth merchants of these days and it highly fascinated Van Leeuwenhoek. Some years later, in 1654 the business man opened his own drapery shop in Delft, but he would never lose the interest in glass processing and only about ten years later he already knew how to grind lenses and produce his first microscopes himself.

It must be noted, that microscopes with several lenses were used before Van Leeuwenhoek, but the quality was astonishingly bad which increased his motivation to built a microscope with just one perfect lens, which succeeded.

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723)

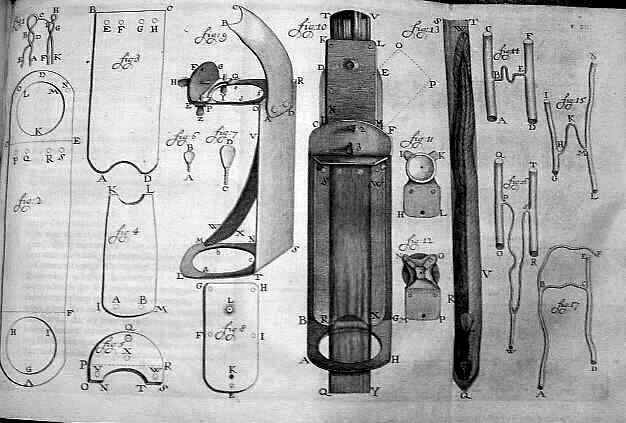

The Professional Amateur

His first observations, which he performed in his free time were rather simple like measuring the numbers of microorganism in certain units of water. However, these kind of observations were almost unique to this point but still, the hobby-biologist was disregarded in the scientific community. All microscopes known by Leeuwenhoek are so-called “simple microscopes”. In principle, they work like a very strong magnifying glass. Since stronger magnifications require stronger curvatures of the single lens, the lenses of such simple microscopes are very small. “Simple” in this context does not refer to ease of manufacture, but to the contrast with “compound microscopes,” which use an objective and eyepiece to provide magnification in two steps (see also light microscope). Today’s microscopes are compound microscopes, with exceptions. Compound microscopes were developed several decades before Leeuwenhoek’s birth. The problem of chromatic aberration was not solved until the 19th century. In Leeuwenhoek’s time, compound microscopes multiplied the problem by using two lenses. They therefore produced poor results, especially in the higher resolution range.

The Royal Society

Eventually in the 1670’s, Van Leeuwenhoek got in touch with the Royal Society of London and was finally able to publish his observations, which instantly caused him to become famous in the scientific community and beyond. Already in 1660, the Royal Society was founded in London. It wanted to establish contact with all those who promoted knowledge of nature, regardless of their nationality or social position. Its first secretary, Henry Oldenburg, maintained numerous correspondences, including with the physician Reinier de Graaf, who was already famous in 1673 and practicing in Delft. In the years before, Leeuwenhoek had obviously been successful in making microscopes and had made first observations with their help. De Graaf was aware of this work and had himself been able to observe various objects through these microscopes on several occasions. In 1668, a microscopic work by the Italian Eustachio Divini appeared in the journal of the Royal Society, the Philosophical Transactions. He had been able to find an animal smaller than any previously seen. Probably in response to this report, de Graaf wrote to Oldenburg that Leeuwenhoek had developed microscopes that were better than any previously known.

The Only Serious Microscopist

The members of the Royal Society told Oldenburg to contact Leeuwenhoek directly and ask for illustrations of the observed objects. Leeuwenhoek found himself unable to draw, so he had them drawn and sent the result to London. Parallel to this letter, Constantijn Huygens sent a letter praising Leeuwenhoek to Robert Hooke, microscopist and member of the Royal Society. From this time until the end of his life, Leeuwenhoek sent numerous letters to the Royal Society, many of which were printed, often abridged, in English translation in the Transactions. By the end of the 17th century, Leeuwenhoek was the only serious microscopist in the world. He had neither rivals nor imitators. Microscopes were otherwise used only as a pastime.

The Father of Microbiology

Leeuwenhoek communicated all his observations in over 300 letters. He sent the first of 215 to the Royal Society in London in 1673. 119 of these were published at least in part in the Philosophical Transactions. This makes him to this day (as of 2014) by far the author with the most publication in this journal since its founding in 1665, and thus in over 350 years. He also corresponded with many other scholars. That Leeuwenhoek had no training as a scientist is evident from his letters. In them he describes his observations without putting them in order, interspersed with personal details, to suddenly come to a completely different subject. However, he always clearly distinguished what he had actually observed and how he interpreted his observations, a characteristic also of modern science. This clarity is rare in scientific literature of his time. Leeuwenhoek described more than 200 species, but he often did not describe them precisely enough to be able to identify them with certainty today. He was able to produce 500 high quality lenses and at least 25 microscopes of different types. One was even capable to magnify up to 500 times and with it he was able to majorly contribute to the new scientific field of microbiology. He for instance discovered the infusoria, bacteria, a cell’s vacuole and spermatozoa. About the last discovery there were several serious troubles Van Leeuwenhoek had to face with theologists.

Later Years

Leeuwenhoek was financially well secured in his old age. He performed his municipal duties until about the age of 70, but continued to receive the corresponding salary thereafter. His fortune was almost 60,000 guilders, and his estate included numerous microscopes made of silver as well as three made of gold. Leeuwenhoek died in Delft on August 26, 1723, almost exactly two months before his 91st birthday.

“Here rests Anthony van Leeuwenhoek, oldest member of the Royal Society in London. Born at Delft, October 24, 1632, and died August 26, 1723, aged 90 years, 10 months, and 2 days. To the reader: If any, O wanderer, have reverence for age and wonderful gifts, Set your step here respectfully. Here rests the graying science in Leeuwenhoek…”

– Epitaph in the Oude Kerk in Delft

Leeuwenhoek: The First Master of Microscopes, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Antonie van Leeuwenhoek on BBC History

- [2] Antonie van Leeuwenhoek at Wikidata

- [3] Leeuwenhoek at the University of California, Berkeley

- [4] Maria Sibylla Merian and her Love for Nature’s Details, SciHi Blog

- [5] Edward Murray East and the Hybrid Corn , SciHi Blog

- [6] Ernst Haeckel and the Phyletic Museum , SciHi Blog

- [7] Leeuwenhoek: The First Master of Microscopes, Journey to the Microcosmos @ youtube

- [8] Corliss, John O (1975). “Three Centuries of Protozoology: A Brief Tribute to its Founding Father, A. van Leeuwenhoek of Delft”. The Journal of Protozoology. 22 (1): 3–7.

- [9] Dobell, Clifford (1960) [1932]. Antony van Leeuwenhoek and His “Little Animals”: being some account of the father of protozoology and bacteriology and his multifarious discoveries in these disciplines (Dover Publications ed.). New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

- [10] de Kruif, Paul (1926). “I Leeuwenhoek: First of the Microbe Hunters”. Microbe Hunters. Blue Ribbon Books. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company Inc. pp. 3–24.

- [11] Leeuwenhoek Timeline via Wikidata

Pingback: Where Do Germs Come from in Your Facility? 10 Hiding Places - Where Do Germs Come from in Your Facility? 10 Hiding Places