Anna Komnena (1083-1153)

Anna Komnena was a Byzantinian Princess in the 11th century. She is considered one of the world’s first female historian and a major source of information about the reign of her father, Alexius I. in the times of the crusades. Of course this is rather unusual for the time being, that a princess writes about the life of her father, The Alexiad, and even more that this piece of writing should become one of the most valuable works in the collection of the Byzantine Historians.

“The stream of Time, irresistible, ever moving, carries off and bears away all things that come to birth and plunges them into utter darkness, both deeds of no account and deeds which are mighty and worthy of commemoration.”

— Anna Komnena, The Alexiad, Preface

Born and Bred in the Purple

Anna Komnena was the daughter of the Emperor Alexius I. (Komnenus) and his wife Irene, and was born on December 1, 1083, being the eldest of seven siblings. She notes her imperial heritage in the Alexiad by stating that she was “born and bred in the purple.”, which also is a hint that she was born in the Porphyra Chamber (the purple chamber) of the imperial palace of Constantinople. Anna also notes in the Alexiad in her early childhood that she was raised by the former empress, Maria of Alania, who was the mother of Anna’s first fiancé, Constantine Doukas, which was common custom by these times to be raised by the future mother-in-law. In 1087, Anna’s brother, John II Komnenos, was born.

Languages and Sciences

According to her own account, she emphasizes on her experience with literature, Greek language, rhetoric, and sciences. She was trained in subjects that included astronomy, medicine, history, military affairs, geography, and mathematics. Anna also studied philosophy and was a follower of Christian Aristotleism, which had neo-Platonic traits. As was customary for nobility in the medieval times, Anna was betrothed already at infancy. In 1097, she married an accomplished young nobleman, the Caesar Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger, a renowned statesman, general, and historian that had contested the throne before the accession of Alexios I. However, she herself would have preferred to remain single.

Managing a Hospital and Orphanage

Anna was placed in charge of a large hospital and orphanage that her father built for her to administer in Constantinople. The hospital was said to hold beds for 10,000 patients and orphans. There, Anna taught medicine and was considered an expert on gout.

The Succession to the Throne

In 1118 Anna, together with her mother, tried to persuade the emperor on his deathbed to disinherit his son Kaloioannes (1118-1143) and instead transfer the succession to Anna’s husband. But Alexios, determined to make John his successor, secretly sent his seal ring to his son. According to other sources, John and his brother Isaac secretly invaded the Mangana Palace and stole the ring. After the death of Alexios, perhaps as a result of pneumonia, John secured the palace, had himself proclaimed emperor by the army and senate and confirmed by the patriarch of Constantinople. Anna and her mother Irene then conspired the same year with the aim of bringing Anna’s husband Nikephoros to the throne. However, the conspiracy was uncovered, possibly even by Nikephoros himself, who had no desire to become emperor. The participants escaped with light punishments. Their possessions were confiscated, Irene and Anna were banished to the monastery, where Irene died in 1123.

Anna’s Husband Nikephoros Bryennios

Anna’s husband, Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger had been working on an essay that he called “Material For History“, which focused on the reign of Alexios I. However, Nikephoros died in 1137 in Constantinople from a wound he had sustained during a campaign to Syria and Cilicia without ending the history he had begun on the way.

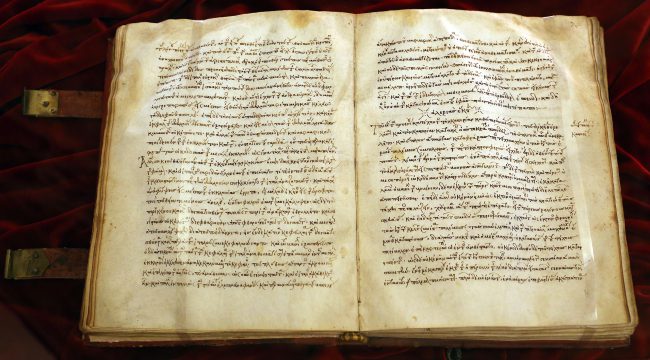

Anna Komnene’s Alexiad, 12th century manuscript, Sailko, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The only Eyewhitness Account

At the age of 55, Anna took it upon herself to finish her husband’s work, calling the completed work the Alexiad, the history of her father’s life and reign from 1069 to his death in 1118 in Greek. The 15 volumes of the Alexiad is today the main source of Byzantine political history from the end of the 11th century to the beginning of the 12th century. In her writings Anna provided insight on political relations and wars between Alexios I and the West. She vividly described weaponry, tactics, and battles. Despite always being on the moral side of her father, her account of the First Crusade is of great value to history because it is the only Hellenic eyewitness account available.

Literary Style

Anna Komnene’s literary style is fashioned after the antique historians such as Thucydides, Polybios, and Xenophon. Her work also contains quotations from Homer, Herodotus,[3] Sophocles, Plato, Aristotle, John of Epiphany and many others. Her style, with numerous direct commentaries, resembles that of Michael Psellos, but influences from late antique historians can also be found. In the descriptions of the unsuccessful treatment of her father by his doctors, the medically versed Anna shows humoral-pathological knowledge of Galenus.[4] For the most part, the chronology of events in the Alexiad is sound, except for those that occurred after Anna’s exile to the monastery, when she no longer had access to the imperial archives.

The exact date of Anna Komnena’s death is uncertain. The date of her death is unknown, but she was still at work on her history in 1148.

The princess who rewrote history – Leonora Neville, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Anna Komnena, The Alexiad, translated by Elizabeth A. Dawes in 1928

- [2] Anna Komnena at Wikidata

- [3] Herodotus – the Father of History, SciHi Blog

- [4] Galenus of Pergamon – The most Accomplished Physician of Antiquity, SciHi Blog

- [5] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 59

- [6] Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, pp. 59–60

- [7] The princess who rewrote history – Leonora Neville, TED-Ed @ youtube

- [8] Timeline of female historians before 1800, via Wikidata