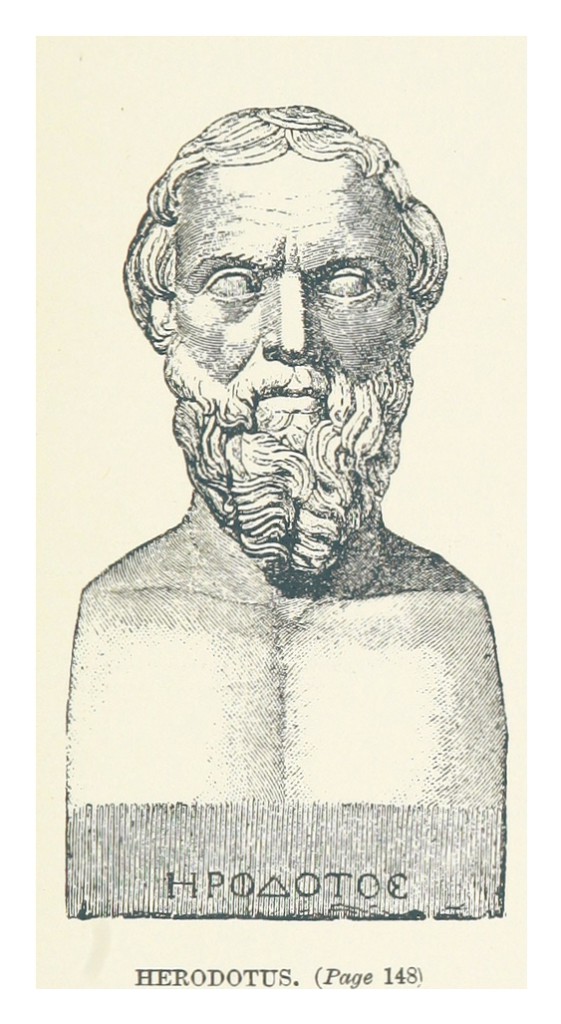

Herodotus (c. 484 -c. 425 BC), from Pictures from Greek Life and Story, by Church, Alfred John (1893)

About in 484 B.C., ancient Greek historian Herodotus was born. A contemporary of Socrates, he is widely referred to as “The Father of History“. Herodotus was the first historian known to have broken from Homeric tradition to treat historical subjects as a method of investigation: specifically by collecting his materials systematically and critically, and then to arrange them into a historiographic narrative. Despite Herodotus‘ historical significance, little is known of his personal history.

“Here are presented the results of the enquiry carried out by Herodotus of Halicarnassus. The purpose is to prevent the traces of human events from being erased by time, and to preserve the fame of the important and remarkable achievements produced by both Greeks and non-Greeks; among the matters covered is, in particular, the cause of the hostilities between Greeks and non-Greeks.”

— Herodotus, The Histories

The Life of Herodotus

Modern scholars generally turn to Herodotus‘s own writing for reliable information about his life, complemented by later sources, such as e.g. the 10th century Byzantine encyclopedia “Suda“. According to the Suda, Herodotus was born at Halicarnassus in an influential family the son of Lyxes and Dryo, the brother of Theodorus, and related to Panyassis, an epic poet of the time. Halicarnassus was part of the Persian empire at that time, though a Dorian city, and maybe the young Herodotus heard local eye-witness accounts of events within the empire and of Persian preparations for the invasion of Greece. Herodotus reveals affection for the island of Samos and this is an indication that he might have lived there in his youth. Halicarnassus was an outward-looking, international-minded port within the Persian Empire and the historian‘s family could well have had contacts in countries under Persian rule, facilitating his travels and his researches. His eye-witness accounts indicate that he traveled in Egypt probably sometime after 454 BC or possibly earlier in association with Athenians. He probably traveled to Tyre next and then down the Euphrates to Babylon. Sometime around 447 BC, he migrated to Athens, but was unsuccessful in applying for a citizenship. Shortly afterwards, he migrated to Thurium. Intimate knowledge of some events in the first years of the Peloponnesian War indicate that he might have returned to Athens, in which case it is possible that he died there during an outbreak of the plague. There is nothing in his work that can be dated with any certainty to later than 430, and it is generally assumed that he died not long afterwards, possibly before he was at age 60.

The Histories

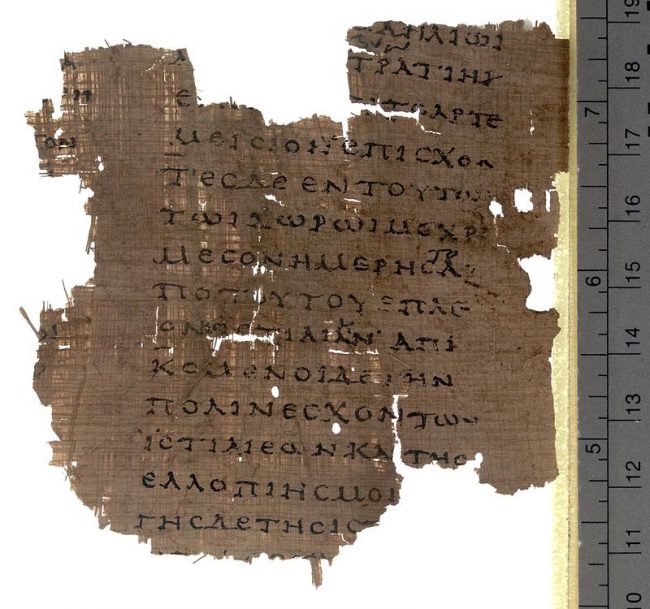

But, it is not Herodotus’ life we are interested in, it’s his work on history, “The Histories“. It contains an investigation of the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars and including a wealth of geographical and ethnographical information. Although some of his stories were fanciful and others inaccurate, Herodotus states he was reporting only what was told to him and was often correct in his information. Herodotus aimed to “both inform and delight his audience in writing the story of how a small and internally divided jumble of Greek city states united to repel two successive invasions by the mighty Persian Empire” [1]. Divided by later editors into nine books named after the Muses, the History traces the growth of the Persian empire, starting with Croesus of Lydia, though Cyrus and Xerxes. The pivotal event of the History is the Battle of Marathon (490 BC), where the Persians were defeated by the Greeks. A decade later the Persians, led by Xerxes, returned but were decisively defeated at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC. One can only wonder what the world would have been like if the nascent Greek democracy and high classical culture had been nipped in the bud by Persian despotism.[4]

Fragment from the Histories VIII on Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 2099, early 2nd century AD

The Nature of the World

Earlier writers had produced what Herodotus called “logographies”: These were what we might call travelogues, disconnected tales about places and people that did not cohere into a narrative whole. By contrast, Herodotus used all of his “autopsies” to build a complete story that explained the why and the how of the Persian Wars.[5] Interestingly, the ultimate goal of the histories seems to be an everlasting subject that also matters today: the clash of civilizations, i.e. the inability of the peoples of east and west to live together in peace. Besides, the accuracy of the works of Herodotus has been controversial since his own era. Herodotus provides much information about the nature of the world and the status of science during his lifetime, often engaging in private speculation. For example, he reports that the annual flooding of the Nile was said to be the result of melting snows far to the south, and he comments that he cannot understand how there can be snow in Africa, the hottest part of the known world, offering an elaborate explanation based on the way that desert winds affect the passage of the Sun over this part of the world.

Lost in Translation

Another example that was rejected over the centuries was his claim of fox-sized ants in Persia who spread gold dust when digging their mounds. But, in 1984, French author and explorer Michel Peissel confirmed that a fox-sized marmot in the Himalayas did indeed spread gold dust when digging and that accounts showed the animal had done so ever since as the villagers had a long history of gathering this dust. Peissel also explained that the Persian word for `mountain ant’ was very close to their word for `marmot’ and so it was established that Herodotus was not making up his giant ants but was the victim of a misunderstanding in translation.[6] Although Herodotus considered his “inquiries” a serious pursuit of knowledge, he was not above relating entertaining tales derived from the collective body of myth, but he did so judiciously with regard for his historical method, by corroborating the stories through enquiry and testing their probability.

Trustworthiness

There has been disagreement about the credibility of Herodotus since ancient times. Plutarch wrote a tract about 450 years later in which he condemned him as a liar. In recent research, some see him as a methodologically astonishingly well-working reporter for his time, while others believe that he had invented many things freely and only feigned eyewitness testimony. To date, no uniform opinion has emerged in research on this. Herodotus’ writings were recognized as a new form of literature soon after their publication.

Paul Cartledge discusses Tom Holland’s English translation of Herodotus, Roman Society, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Paul Sheridan: The Inessential Guide to Herodotus, in anecdotesfromantiquity.com

- [2] Edward Gibbon and the Science of History, SciHi blog, April 27, 2013.

- [3] Herodotus’ Histories: the 28 logoi

- [4] The History of Herodotus, parallel English/Greek, English translation: G. C. Macaulay (1890)

- [5] Herodotus of Harlikarnassos, at history.com

- [6] Joshua J. Mark: Herodotus, in Ancient History Encyclopedia

- [7] Herodotus of Halicarnassus at Livius.org

- [8] Works by or about Herodotus at Internet Archive

- [9] The History of Herodotus, at The Internet Classics Archive

- [10] Herodotus at Wikidata

- [11] Paul Cartledge discusses Tom Holland’s English translation of Herodotus, Roman Society @ youtube

- [12] Timeline of ancient Greek Historians, via Wikidata and DBpedia