Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), Painting by John Hayls, 1666

On February 23, 1633, English naval administrator and Member of Parliament Samuel Pepys was born, who is now most famous for the diary he kept for a decade while still a relatively young man. The detailed private diary Pepys kept from 1660 until 1669 was first published in the 19th century, and is one of the most important primary sources for the English Restoration period. Personally, I really enjoyed reading Samuel Pepys’ diary. Especially because he provides us with such an unpretentious view on historic events connected to daily life activities and the human comedy. This is a definite must read for everybody interested in history.

“Blessed be God, at the end of the last year I was in very good health, without any sense of my old pain, but upon taking of cold. “(Jan 1, 1660)

Family Background and Early Years

In this harmless and relaxed manner, one of the most important primary sources of English history in the 17th century begins. Samuel Pepys was born on February 23rd 1633 in Salisbury Court of Fleet Street. His father, John, was a tailor, his mother Margaret Kite was sister of a Whitechapel butcher and Samuel was fifth in a line of eleven children. In 1642, Samuel was sent to Huntingdonshire to live with his uncle, because of his health and fears of the Plague, from which several of his brothers died. There, he attended grammar school, followed by St Paul’s School after his return to London. In 1650, he enteredCambridge University, where he was admitted as a sizar to Magdalene College; he moved there in March 1651 and took his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1654.

The Removal of the Bladder Stone

“Then to the King’s Theatre, where we saw Midsummer’s Night’s Dream, which I had never seen before, nor shall ever again, for it is the most insipid ridiculous play that ever I saw in my life.” (September 29, 1662)

Pepys was employed as secretary to Edward Montagu, a distant relative who was a councillor of state during the Cromwellian protectorate and later served Charles II. In 1655, Pepys married 15-year-old Elizabeth Marchant de Saint-Michel, daughter of a Huguenot exile, and became a clerk of the Exchequer. In 1658, he underwent a dangerous operation for the removal of a bladder stone. This cannot have been an easy option, as the operation was known to be especially painful and hazardous. Every year on the anniversary of the operation, he celebrated his recovery. In 1660, Pepys was made Clerk of the King’s Ships to the Navy Board.

“Up; and put on my coloured silk suit very fine, and my new periwigg, bought a good while since, but durst not wear, because the plague was in Westminster when I bought it; and it is a wonder what will be the fashion after the plague is done, as to periwiggs, for nobody will dare to buy any haire, for fear of the infection, that it had been cut off of the heads of people dead of the plague.” (Sep 3, 1665, The Great Plague)

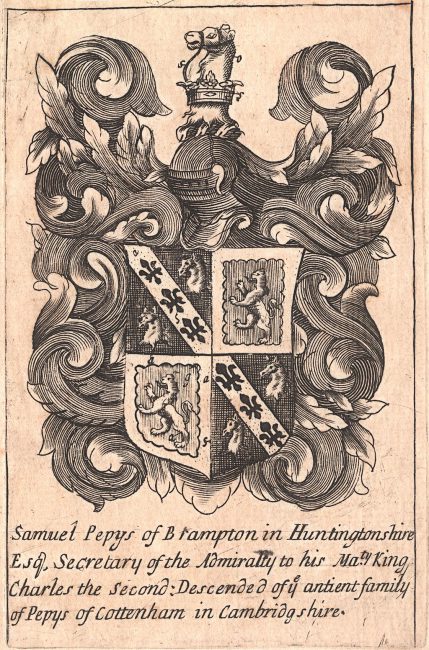

Bookplate, c. 1680–1690, with arms of Samuel Pepys.

The Famous Diary

“And so to Mrs. Martin and there did what je voudrais avec her, both devante and backward, which is also muy bon plazer. “(June 3, 1666)

Pepys began writing his diary on 1 January 1660 at age 27. The diary is written in the shorthand system established by Thomas Shelton, with names in longhand. Aside from day-to-day activities, Pepys also commented on the significant and turbulent events of his nation. It ranges from private remarks, including revelations of infidelity – to detailed observations of events in 17th century England – such as the Great Plague of 1665, the Great Fire of London [5], the arrival of the Dutch fleet and the coronation of King Charles II – including some of the key figures of the era of Restoration, such as Sir Christopher Wren [6] and Sir Isaac Newton [7]. The women whom he pursued, his friends, and his dealings are all laid out. His diary reveals his jealousies, insecurities, trivial concerns, and his fractious relationship with his wife. It has been an important account of London in the 1660s. The juxtaposition of his commentary on politics and national events, alongside the very personal, can be seen from the beginning and make the diary such a unique resource. Pepys stopped writing his diary in the spring of 1669 – at the age of 36, his eyesight had gotten worse, and he feared losing his sight altogether. But, he never actually went blind.

Further Steps in Pepys’ Career

“Some of our maids sitting up late last night to get things ready against our feast today, Jane called up about three in the morning, to tell us of a great fire they saw in the City. So I rose, and slipped on my night-gown and went to her window, and thought it to be on the back side of Mark Lane at the farthest; but, being unused to such fires as followed, I thought it far enough off, and so went to bed again, and to sleep.” (Sep 2, 1666, The Great Fire of London)

The following 34 years brought Samuel Pepys more appointments and acclaim. He became a Member of Parliament and Secretary of the Admiralty in 1673, and took part in organizing the navy during the war with the Dutch in 1672-74. In 1679, Pepys was accused of giving naval secrets to the French in the Popish Plot, and he was imprisoned in the Tower for six weeks. However, he was soon cleared of charges and was reinstated as Secretary to the Admiralty in 1684. He served as President of the Royal Society from 1684-86.[8] Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica was published during this period and its title-page bears Pepys’ name. In 1689, Pepys retired from public service at the accession of King William III.

Later Years

“I went out to Charing Cross, to see Major-general Harrison hanged, drawn and quartered; which was done there, he looking as cheerful as any man could do in that condition.” (October 13, 1660)

In 1701, when his health began to fail, he moved out of London into the town of Clapham, where he completed the collection of his private library of 3,000 books, which was an amazing number of books by the time. When Pepys died on May 26, 1703, his library, including his Diary, was bequeathed to his nephew John Jackson, and subsequently to Magdalen College under the condition that the contents would never be altered. A century passed, however, before the shorthand diary was transcribed by the Reverend John Smith. He laboured at this task for three years, from 1819 to 1822, unaware that a key to the shorthand system was also stored in Pepys’s library a few shelves above the diary volumes. Smith’s transcription was the basis for the first published edition of the diary, edited by Lord Braybrooke, released in two volumes in 1825.

Did satisfy myself mighty fair in the truth of the saying that the world do not grow old at all, but is in as good condition in all respects as ever it was. (February 3, 1667)

Lecture on Samuel Pepys, Samuel Johnson and James Boswell, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Diary of Samuel Pepys

- [2] Samuel Pepys – a biography

- [3] Jokinen, Anniina: Life of Samuel Pepys at Luminarium, 2003.

- [4] [in German] Rezension zu den Tagebüchern: So nah und doch so fern… (aus dem Biblionomicon)

- [5] The Great Fire of London, SciHi Blog, September 2, 2013.

- [6] Sir Christopher Wren – Baroque Architect, Philosopher, Scientist, SciHi Blog, October 20, 2017.

- [7] Standing on the Shoulders of Giants – Sir Isaac Newton, SciHi Blog, January 4, 2018.

- [8] The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, SciHi Blog, March 6, 2015.

- [9] Samuel Pepys at Wikidata

- [10] Samuel Pepys at Reasonator

- [11] Lecture on Samuel Pepys, Samuel Johnson and James Boswell, Holmnan’s History @ youtube

- [12] Works by or about Samuel Pepys at Internet Archive

- [13] Timeline of famous diarists, via Wikidata