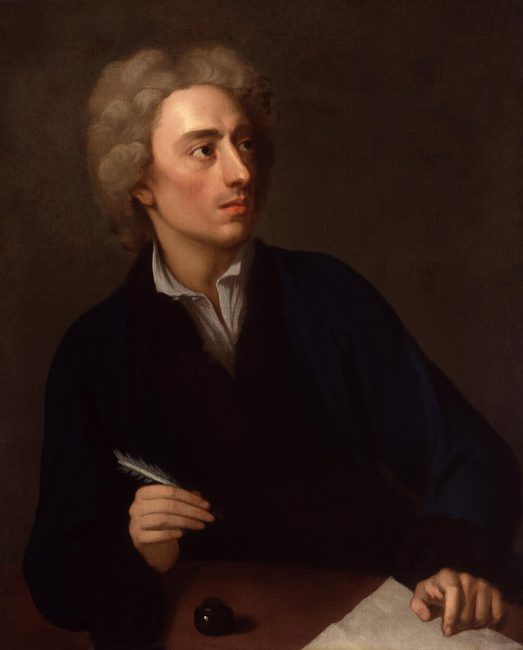

Alexander Pope (1688 – 1744)

On May 21, 1688, English poet Alexander Pope was born. Pope is regarded as one of the greatest English poets, and the foremost poet of the early eighteenth century. He is best known for his satirical and discursive poetry, including The Rape of the Lock, The Dunciad, and An Essay on Criticism, as well as for his translation of Homer.

“Nature and nature’s laws lay hid in night;

God said “Let Newton be!” and all was light.”

– Alexander Pope’s epigram on Newton [3]. However, Pope had not been allowed to place this poem in Westminster Abbey as an epitaph.

Alexander Pope’s Youth and Education

Alexander Pope was born in London, UK, in 1688, the year of the Glorious Revolution, into a Catholic family as the son of a linen merchant. Due to the penal laws that were in force at the time, in order not to jeopardize the status of the established Anglican Church, he could obtain his education almost only outside the “normal” schools. A priest known to the family taught him the classical languages Latin and Greek, later he also learned French and Italian. Since the age of 15 Alexander Pope wrote his own poems. In 1700 his family moved to Binfield, Berkshire, in Windsor Forest. Pope fell ill with tuberculosis and asthma and subsequently developed a curvature of the spine, which he was later often reproached for. He grew to be only 1.38 metres tall and wore a bodice as back support. Pope was already removed from society because he was Catholic, and his poor health alienated him further.

First Literary Success

“Happy the man whose wish and care

A few paternal acres bound,

Content to breathe his native air

In his own ground.”

– A. Pope, “Ode on Solitude”, st. 1 (c. 1700)

In May 1709, Pope’s Pastorals was published in the sixth part of bookseller Jacob Tonson’s Poetical Miscellanies. After returning to London in 1711, Pope published his first major work: An Essay on Criticism. This manifesto of literary criticism, in the form of an essay on verse, was his first breakthrough, and he gained access to literary circles, initially from the opposition Whig Party. In 1713 he joined the Tories and became a member of the Scriblerus Club, where he met Jonathan Swift,[1] John Gay, William Congreve and Robert Harley. The resulting fictional Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus were in turn caricatured in the satire The Scribleriad by Richard Owen Cambridge. The year before, Pope had already published a first version of The Rape of the Lock, a comic epic about the war of the sexes, which further boosted his popularity. As in his other epics, Pope proved his artistic mastery of the classical epic style, without sharing its basis of a mythical-heroicized worldview, and thus successfully transferred the traditional epic into a contemporary form.

Translating the Classics

“He serves me most, who serves his country best.”

– A. Pope, The Iliad of Homer (poetic interpretation, 1715 to 1720)

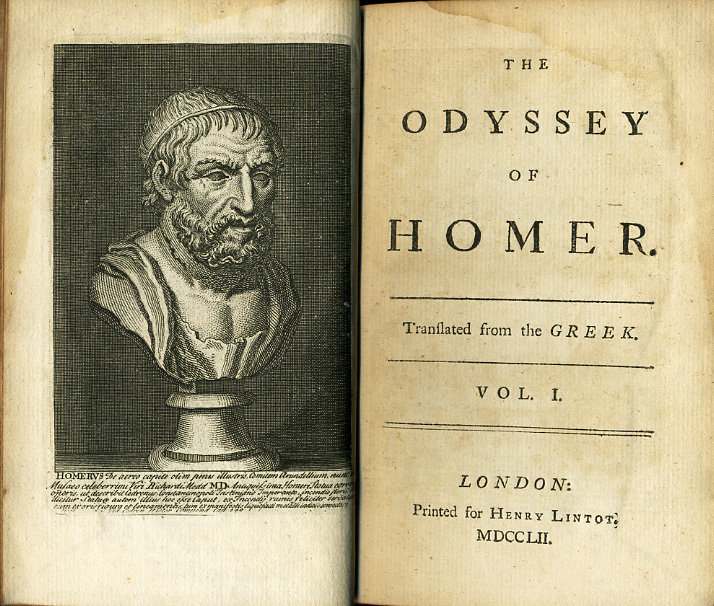

Pope admired classical authors like Horace, Virgil, Homer and chose them as literary models. His greatest achievements include English translations of the Iliad (1715-1720, 6 volumes) and Homer’s Odyssey (1725-1726, 5 volumes), while for the later he secretly enlisted the help of two co-authors. His translations of Homer’s works, however, were linguistically more like recompositions than faithful translations; by transforming Homer’s rough or powerful style into an elegant form of language that corresponded to contemporary stylistic sensibilities, he also attempted to break down possible barriers and bring the ancient poet closer to the educated classes of England. Endowed with the income from these financially very successful translations, he moved once again, now to Twickenham, thus escaping the pressure of the anti-catholic Jacobites.

Front page of Alexander Pope’s translation of Homer’s Odyssey from 1752

Horticulture and Landscape Gardening

“Histories are more full of Examples of the Fidelity of dogs than of Friends.”

– A. Pope, Letter to Henry Cromwell (19 October 1709)

In Twickenham, Pope also turned to horticulture and landscape architecture. He had an artificial grotto built for which William Borlase, an antiquarian and naturalist with whom he had a long correspondence, taught fossils and minerals. He became friends with his neighbour Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. After this relationship cooled down, he began a lifelong relationship with Martha Blount, whom he often visited at her parents’ house, Mapledurham House, and to whom he bequeathed many of his possessions on his death. In Twickenham he also received many distinguished visitors, including Jonathan Swift, whom he helped to publish Gulliver’s Travels.

Shakespeare

“What dire offence from amorous causes springs,

What mighty contests rise from trivial things!”

– A. Pope, The Rape of the Lock (1712, revised 1714 and 1717)

At about this time the publisher Jacob Tonson asked Pope to obtain a new edition of the Rowe edition of Shakespeare‘s works from 1709.[2] The 6-volume edition was published in 1725 and occupies a special place in the history of editions of Shakespeare’s works, as Pope was the first to collate Shakespeare’s texts by comparing the folio-based Rowe edition with the then available Quartos. However, Pope used the opportunity not so much for a detailed correction of errors as for an aesthetic correction of the texts. He banned whole passages of text that he thought failed in footnotes and, in his opinion, marked good passages with quotation marks and asterisks. While the changes in the text are due to the taste of the times, Pope’s preface to the edition is considered an important document of 18th century literary criticism.

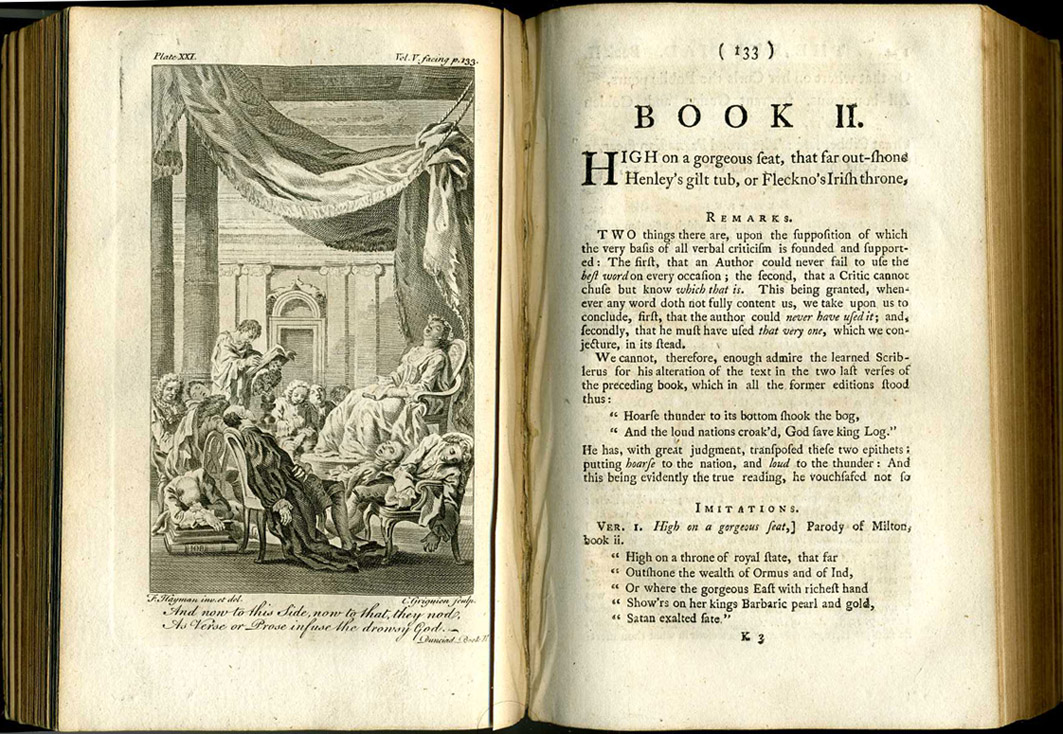

Dunciad Book II 1760 illustration, showing the Goddess and poets asleep. Artist F. Hayman, Engraver C. Grignion, Scanner & uploader Steven J. Plunkett. – 1760 Collected (Warburton) edition of Pope, London, Vol V

Literary Polemic and Satire

“Hope springs eternal in the human breast:

Man never is, but always to be blest.”

– A. Pope, An Essay on Man (1733/34)

When his edition of Shakespeare’s works was attacked by the publicist and Shakespearean editor Lewis Theobald in 1726, he responded in verse form in 1728 with the mocking epic The Dunciad, in which he satirically placed Theobald on the throne of the fools and at the same time settled accounts with the so-called Grub Street, the guild of wage-scribes. In the later and final version of this mocking poem, he expanded his literary polemic of 1742-1743 into a general discussion of the cultural and political decline of the Walpole era, which concluded with the apocalyptic vision of an all-encompassing downfall. With his polished verses and ingenuity, Pope succeeded in making a name for himself as a satirist. With growing influence, he established himself as a kind of public authority. In 1731 he published Moral Essays, three years later An Essay on Man, in which he, following in the footsteps of Greek philosophy and poetry (Sophocles), sings of the splendour and misery of human existence with a high degree of pathos in sometimes poignant verses. At the same time he worked on a publication of his correspondence in literary art form. This made Pope one of the first professional writers of non-dramatic works.

Death

In his last years, Pope himself designed a romantic grotto in his estate, i.e. a tunnel decorated with shells and mirrors, which connected the riverbank of his property with the rear garden section. Pope died on May 30, 1744 and his estate passed to Martha Blount. William Warburton published posthumously The Works of Alexander Pope, in 1751. While Pope is generally regarded today as one of the most important English poets of the 18th century, his work was subsequently largely misunderstood from the perspective of a Romantic view of literature in the 19th century, and only in the 20th century was it adequately appreciated again.

Scott Masson, Alexander Pope, The Rape of the Lock, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Wonderful Worlds of Jonathan Swift, SciHi Blog

- [2] Brush Up Your Shakespeare, SciHi Blog

- [3] Standing on the Shoulders of Giants – Sir Isaac Newton, SciHi Blog

- [4] Works by or about Alexander Pope at Internet Archive

- [5] Lennox, Patrick Joseph (1911). . Catholic Encyclopedia

- [6] Mack, Maynard (1985). Alexander Pope: A Life. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- [7] Cassirer, Ernst (1944). An Essay on Man; an introduction to a philosophy of human culture. Yale University Press.

- [8] Works by or about Alexander Pope at Wikisource

- [9] Alexander Pope at Wikidata

- [10] Scott Masson, Alexander Pope, The Rape of the Lock, Dr Scott Masson @ youtube

- [11] Timeline for Alexander Pope, via Wikidata