Synthetic Production of Penicillin Professor Alexander Fleming, holder of the Chair of Bacteriology at London University, who first discovered the mould Penicillin Notatum. Here in his laboratory at St Mary’s, Paddington, London (1943).

On September 3, 1928, Scottish pharmacologist Alexander Fleming by chance and because of his notorious untidyness discovered Penicillin.

“One sometimes finds, what one is not looking for. When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did.”

— Alexander Fleming [11]

Alexander Fleming – Early Years

Alexander Fleming was born on August 6, 1881 on the Lochfield farm in Darvel, in Ayrshire, Scotland, as the third of four children of farmer Hugh Fleming (1816–1888) from his second marriage to Grace Stirling Morton (1848–1928), the daughter of a neighbouring farmer. He studied medicine at St Mary’s Hospital Medical School in Paddington from 1902. In 1906 he completed his studies but remained at the institute. From 1921 he was deputy director and from 1946 director of the institute, which was renamed the Wright Fleming Institute in 1948. From 1928 to 1948 he held the chair of bacteriology at London University. In his early years Fleming was involved with car vaccines. In 1921 he isolated the enzyme lysozyme, which is found in the protein of chicken egg and in numerous human body secretions and is able to destroy bacteria.

There are various legends that Alexander Fleming saved the life of Winston Churchill or that Fleming’s education was financed by Churchill’s father. These anecdotes, however, cannot be verified by historical sources and have been refuted and proved mythical by various authors. Fleming himself, for example, described in a letter the story according to which his father saved the life of the young Churchill and whose father in turn financed Fleming’s studies as “A wondrous fable“.

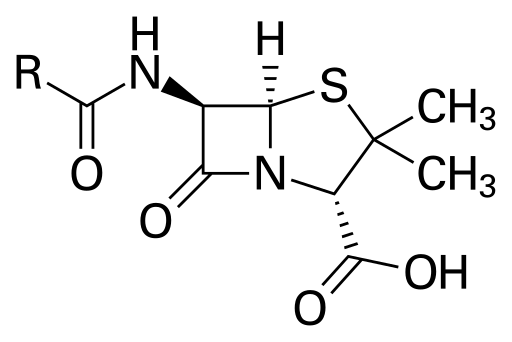

Penicillin core structure, where “R” is the variable group.

The Discovery of Penicillium

In 1927, Alexander Fleming was investigating the properties of staphylococci, a family of bacteria, most of them being harmless and residing on the human skin. Fleming was already well-known from his earlier work, and had developed a reputation as a brilliant researcher, but his laboratory was often untidy. On 3 September 1928, Fleming returned to his laboratory having spent August on holiday with his family. Before leaving, he had stacked all his cultures of staphylococci on a bench in a corner of his laboratory. On returning, Fleming noticed that one culture was contaminated with a fungus, and that the colonies of staphylococci that had immediately surrounded it had been destroyed, whereas other colonies farther away were normal. Fleming grew the mould in a pure culture and found that it produced a substance that killed a number of disease-causing bacteria. He identified the mould as being from the Penicillium genus, and, after some months of calling it “mould juice”, named the substance it released penicillin on 7 March 1929.

Mass Production

Fleming published his discovery in 1929, in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology, but only little attention was paid by the public. Nevertheless, he continued his research, but found that cultivating penicillium was quite difficult, and that after having grown the mould, it was even more difficult to isolate the antibiotic agent. Fleming’s impression was that because of the problem of producing it in quantity, and because its action appeared to be rather slow, penicillin would not be important in treating infection. Also he became convinced that penicillin would not last long enough in the human body (in vivo) to kill bacteria effectively. Many of the clinical tests were inconclusive. In the 1930s, Fleming’s trials occasionally showed more promise, and he continued, until 1940, to try to interest a chemist skilled enough to further refine usable penicillin. Finally he abandoned penicillin, and not long after he did, Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain in Oxford took up researching and mass-producing penicillin with funds from the U.S. and British governments.[10]

Honors and Later Years

Among many other honors, Fleming together with Florey and Chain jointly received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1945. He was also an honorary doctor of twelve American and European universities, commander of the French Legion of Honour and honorary director of Edinburgh University.

Alexander Fleming died of a heart attack in London on 11 March 1955 and was buried in St Paul’s Cathedral in London. In 1999 Time Magazine named Alexander Fleming one of the 100 most important people of the 20th century:

“It was a discovery that would change the course of history. The active ingredient in that mould, which Fleming named penicillin, turned out to be an infection-fighting agent of enormous potency. When it was finally recognized for what it was, the most efficacious life-saving drug in the world, penicillin would alter forever the treatment of bacterial infections.”

(Time Magazine, 29/03/1999)

Eric Sidebottom, David Cranston,

Oxford University surgical lectures: Penicillin and the Legacy of Norman Heatley [12]

Related Articles in the Blog:

- [1] Alexander Fleming at the Nobel Prize Foundation

- [2] Alexander Fleming at Britannica Online

- [3] Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen – The Father of Diagnostic Radiology, SciHi Blog

- [4] Louis Pasteur – The Father of Medical Microbiology, SciHi Blog

- [5] Antonie van Leeuwenhoeck – The Father of Microbiology , SciHi Blog

- [6] Athanasius Kircher – In Search of Universial Knowledge , SciHi Blog

- [7] Edward Jenner’s Fight Against Smallpox, SciHi Blog

- [8] Alexander Fleming at Wikidata

- [9] Bennett, Joan W; Chung, King-Thom (2001), “Alexander Fleming and the discovery of penicillin”, Advances in Applied Microbiology, Elsevier, 49: 163–184

- [10] Ernst Boris Chain and his Research on Antibiotics, SciHi Blog

- [11] Haven, Kendall F. (1994). Marvels of Science : 50 Fascinating 5-Minute Reads. Littleton, Colo: Libraries Unlimited. p. 182. ISBN 1-56308-159-8.

- [12] Eric Sidebottom, David Cranston, Oxford University surgical lectures: Penicillin and the Legacy of Norman Heatley, surgicalsciences @ youtube

- [13] Gaynes, Robert (2017). “The Discovery of Penicillin – New Insights After More Than 75 Years of Clinical Use”. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23 (5): 849–853.

- [14] Flemming Alexander (September 1917). “The Physiological and Antiseptic Action of Flavine (With Some Observations on the Testing of Antiseptics)”. The Lancet. 190 (4905): 341–345.

- [15] Fleming, Alexander (1922). “On a remarkable bacteriolytic element found in tissues and secretions”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 93 (653): 306–317.

- [16] Alexander Fleming Timeline via Wikidata

Pingback: Geschiedenis van de vooruitgang | Feiten Focus