Richard Feynman (1918-1988) ©The Nobel Foundation

On May 11, 1918, famous physicist and nobel laureate Richard Feynman was born. Ever since my first days at university, Feynman has been one of my absolute heroes of science. I’ve heard his name for the first time back in high school, when we learned about Feynman diagrams and I have had heard about his famous physics lectures. But when I had the chance to read his autobiographical book “Surely you’re joking Mr. Feynman – Adventures of a Curious Character” I have to admit that I became a fan. Reading about Feynman and following his wonderful lectures also was one of the (many) reasons why I became a scientist.

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool.”

– Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!, (1985)

Youth and Education

Richard Phillips Feynman was born on May 11, 1918, in Queens, New York City, to Lucille née Phillips, a homemaker, and Melville Arthur Feynman, a sales manager, originally from Minsk in Belarus. When Feynman was 15, he taught himself trigonometry, advanced algebra, infinite series, analytic geometry, and both differential and integral calculus. Feynman also showed technical talents very early on; he was an electric hobbyist and earned additional pocket money by repairing radios. Feynman studied physics as an undergraduate from 1935 to 1939 at MIT, the results of his bachelor thesis are now known as Hellmann-Feynman theorem. From 1939 to 1943 he attended the University of Princeton, where he became assistant to John Archibald Wheeler. In his dissertation under Wheeler in 1942, he also developed his path integral formulation of quantum physics, building on an idea of Nobel Prize winner Paul Dirac.[7]

A Popstar of Quantum Mechanics

Feynman was one of the great popstars of quantum physics. How did that come? The public does know rather little about quantum physics. Feynman took part in the development of the atomic bomb and was in charge of the Space Shuttle Challenger desaster. This alone might even justify his popularity. Furthermore, he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965 for his contributions to the development of quantum electrodynamics. All his life he was a keen popularizer of physics through both books and lectures, notably a 1959 talk on top-down nanotechnology called There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom and the three volume publication of his undergraduate lectures, The Feynman Lectures on Physics. So, I guess the first step to public fame as a scientist for me might be to write undergraduate textbooks (alas the atomic bomb and space shuttle are already history…:). Feynman also became known through his books Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!, where he gives advice on the best way to pick up a girl in a hostess bar, and What Do You Care What Other People Think?. At Caltech, he used a nude/topless bar as an office away from his usual office, making sketches or writing physics equations on paper placemats.

Working for the Manhattan Project

“There are all kinds of interesting questions that come from a knowledge of science, which only adds to the excitement and mystery and awe of a flower. It only adds. I don’t understand how it subtracts.”

– What Do You Care What Other People Think? (1988)

During the Second World War, like many American physicists in Los Alamos, he participated in the Manhattan project, the construction of the first nuclear bomb. One of his tasks was to organize the necessary extensive numerical calculations, but he still had enough time for pranks, as he reports in the essay Los Alamos from below. He brought it to a true mastery in opening his colleagues’ document safes. In Los Alamos, Feynman discovered drumming as one of his passions, in which he improved later during a stay in Brazil.

He got to know his later wife Arline Greenbaum as a teenager, but they only got to know each other after finishing high school. When he moved to Princeton, she was already seriously ill. However, it took a long time for the doctors to diagnose a life-threatening form of tuberculosis. He later arranged for her (now his wife) to be accommodated in a hospital near his place of study, Princeton. During his time in Los Alamos, a hospital was also found in Albuquerque, 100 miles away, where Feynman hitchhiked as often as possible. Despite the serious illness, the two were known to his colleagues as a humorous couple. His wife died on 16 June 1945.

Quantum Electrodynamics

After the war, he was instrumental in formulating quantum electrodynamics, which was presented at the Shelter Island Conference in the late 1940s. His immediate boss in Los Alamos, Nobel Prize winner Hans Bethe, appointed him to his first teaching assignment at Cornell University in New York State, where he remained until 1951.[1] He then became Professor of Theoretical Physics at the Caltech in Pasadena and remained there for the rest of his academic career. There he devoted himself intensively to teaching, and in 1961/62 the well-known Feynman Lectures on Physics were created, which all take an original approach. In 1972 he received the Oersted Medal of the American Association of Physics Teachers for his achievements in teaching physics. However, Feynman did not establish an actual school and he had few doctoral students.

The Laws of Weak Interaction

In the 1950s, Richard Feynman turned to solid-state physics and investigated, among other things, superfluidity (a macroscopic quantum state that can be observed at low temperatures, for example with liquid helium). Together with the Nobel Prize winner Murray Gell-Mann, he developed a new formulation of the laws of weak interaction (vector-axial vector form), which reflected the parity violation during beta decay just discovered at the time.[2] In 1965 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his contributions to the development of quantum electrodynamics. In the late 1960s and 1970s he worked on the expansion of the Parton image of high-energy scattering processes, which is now integrated into quantum chromodynamics.

Parallel and Quantum Computing

In 1981 Feynman asked the question Can (quantum) physics be (efficiently) simulated by (classical) computers? and came to the conclusion that this is best done with quantum computers, a field of research that is very topical today. His interest in computers also led him to become a technical consultant in Daniel Hillis’ Thinking Machines company, which produced the massively parallel connection machine. Throughout his life, Feynman practiced a practical and descriptive approach to physics that directly followed his physical intuition. He quickly encountered abstract discussions and schematic, superficial thinking with impatience. Many of his contributions to physics he communicated only orally in discussions to colleagues, where they became part of “folklore” and were often published much later.

“I don’t know anything, but I do know that everything is interesting if you go into it deeply enough.”

– Richard Feynman, From Omni interview, “The Smartest Man in the World” (1979)

The Challenger Disaster

In 1986 he was appointed to the commission of inquiry into the Challenger disaster. His public appearance became known in which he demonstrated the consequences of frost on the sealing rings of the solid fuel tanks with a glass of ice water. His report, which differed from the majority, was critical of NASA’s bureaucratic organization. It was only against resistance that his minority report was annexed to the official report. Feynman had threatened to withdraw from the Commission if his views were not taken into account. His report ended with the sarcastic and, for those responsible at NASA, devastating statement: “For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.”

Richard Feynman died on February 15, 1988, at age 69. His last words were, “Good thing you only have to die once, it’s so boring.”

The Great Explainer

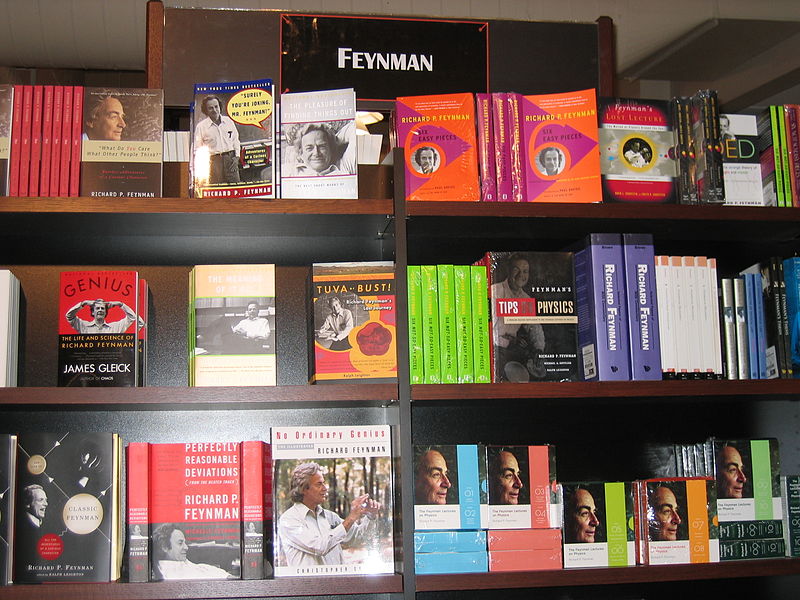

The Bookstore at Caltech has an entire section of books written by and about Richard Feynman, and people think it is even worth while to put this fact including a photograph into wikipedia. Feynman has been called the “Great Explainer”. He gained a reputation for taking great care when giving explanations to his students and for making it a moral duty to make the topic accessible. His guiding principle was that if a topic could not be explained in a freshman lecture, it was not yet fully understood.

Feynman section at Caltech bookstore

Richard Feynman: Can Machines Think?, [5]

Related Articles of Yovisto Blog:

- [1] Hans Bethe and the Energy of the Stars, SciHi blog

- [2] Murray Gell-Mann and the Quarks, SciHi blog

- [3] The Feynman Lectures on Physics Website by Michael Gottlieb, assisted by Rudolf Pfeiffer and Caltech

- [4] Richard Feynman on Wikidata

- [5] Richard Feynman: Can Machines Think?, This is a Q&A excerpt on the topic of AI from a lecture by Richard Feynman from September 26th, 1985. Lex Clips @ youtube

- [6] There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom, SciHi Blog

- [7] Paul Dirac and the Quantum Mechanics, SciHi Blog

- [8] Richard Feynman (Interviews, with and about) – American Institute of Physics

- [9] “Richard P. Feynman – Biographical”. The Nobel Foundation.

- [10] Gribbin, John; Gribbin, Mary (1997). Richard Feynman: A Life in Science. Dutton.

- [11] Schweber, Silvan S. (1994). QED and the Men Who Made It: Dyson, Feynman, Schwinger, and Tomonaga. Princeton University Press

- [12] Feynman, Richard P. (1999). Robbins, Jeffrey (ed.). The Pleasure of Finding Things Out: The Best Short Works of Richard P. Feynman. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus Books.

- [13] Feynman, Richard P. (1985). Ralph Leighton (ed.). Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!: Adventures of a Curious Character. W. W. Norton & Co

- [14] Timeline for Richard Feynman, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol: #40 | Whewell's Ghost