Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff (1699-1753)

On February 17, 1699, Prussian painter and architect Hans Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff was born. Influenced as an architect by French Baroque Classicism and by Palladian architecture, with his interior design and the backing of king Frederick the Great, he created the basis for the Frederician Rococo style. Von Knobelsdorff is best known as architect of Sanssouci Palace in Potsdam just outside Berlin for Frederick the Great. Actually, I lived in the direct neighborhood of the Sanssouci palace in Potsdam. Therefore it will be my pleasure today to tell you the story of its architect.

Von Knobelsdorff – Early Years

Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff, the son of Silesian landed gentry, was born on the estate of Kuckädel (now Polish Kukadlo) near Crossen (now the Polish city Krosno Odrzańskie) on the Oder River. After the early death of his father he was raised by his godfather, the chief senior forester Georg von Knobelsdorff. In keeping with family tradition he began his professional career in the Prussian army. Already at 16 years of age he participated in a campaign against King Charles XII of Sweden, and in 1715 in the siege of Stralsund.

He developed his artistic talents in self-study and after leaving military service he arranged to be trained in various painting techniques by the Prussian court painter Antoine Pesne. Knobelsdorff also acquired additional expertise in geometry and anatomy. He saw his professional future in painting, but his interest in architecture developed from representing buildings in his pictures. Later, the pictorial aspect of his architectural sketches was often noted and met with varying reactions. Especially Frederick the Great, commented positively on the architect’s “picturesque style” (gout pittoresque).

A Moderating Influence for the Heir to the Throne

Knobelsdorff acquired the expertise needed for his new profession again primarily in self-study, after a brief period of training under the architects Kemmeter and von Wangenheim. Knobelsdorff gained the attention of King Frederick William I of Prussia (the “Soldier-King”), who had him join the entourage of his son, crown prince Frederick, later King Frederick II (Frederick the Great). After his failed attempt to flee Prussia and subsequent imprisonment in Küstrin, (now Polish Kostrzyn nad Odrą), Frederick had just been granted somewhat more freedom of movement by his strict father. Apparently, the king hoped that Knobelsdorff, as a sensible and artistically talented nobleman, would have a moderating influence on his son.

The Architect of Frederick the Great

At the time the crown prince, who had been appointed a colonel when he turned 20, took over responsibility for a regiment in the garrison town of Neuruppin. Knobelsdorf became his partner in discussions and advised him on issues of art and architecture. Immediately in front of the city walls they jointly planned the Amalthea garden, which contained a monopteros, a little Apollo temple of classical design. This was the first construction of its type on the European continent and Knobelsdorff’s first creation as Frederick the Great’s architect.

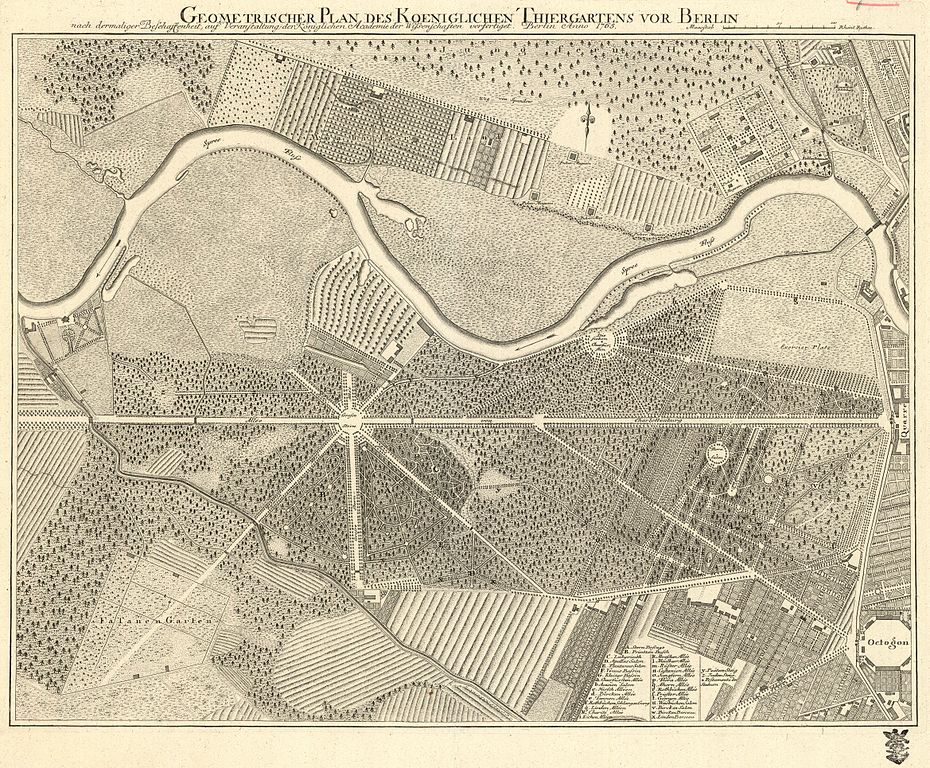

Thiergarten Berlin (1765)

The Obligatory European Tour

In 1736 the crown prince gave Knobelsdorff an opportunity to go on a study tour to Italy, which included Rome, Naples and vicinity, Florence and Venice. In 1740, shortly after Frederick assumed the throne, Knobelsdorff was sent on a second study tour to Paris and Flanders. After his return he was appointed head custodian of royal buildings and Rheinsberg palace was where Knobelsdorff received his first major architectural challenge. After preliminary work by the architect and builder Kemmeter and in regular consultation with Frederick, Kobelsdorff gave the ensemble its present form.

Redesigning Berlin

Already in Neuruppin and Rheinsberg Knobelsdorff had designed together with the crown prince gardens which followed a French style. On November 30, 1741, Frederick II, now king, issued a decree which initiated the redesign of the Berlin Tiergarten to make it the “Parc de Berlin”. As a precondition to redesigning the Tiergarten, large portions of the grounds had to be drained. In many cases Knobelsdorff gave the necessary drainage ditches the form of natural waterfalls, a solution which Friedrich II later praised. In its main axis, a path was created which extended the boulevard Unter den Linden through the Tiergarten to Charlottenburg, lined with hedges, and the junction of eight avenues marked by the Berlin victory column (Siegessäule) was decorated with 16 statues. Furthermore, Knobelsdorff expanded Montbijou Palace, the summer residence, and after 1740 the widow’s seat, of queen Sophie Dorothee of Prussia, the mother of Frederick II. He added a new wing the the Berlin Charlottenburg Palace, the largest palace in Berlin. But, the king’s interest in Charlottenburg waned as he began to consider Potsdam as a second official residence, and first turned to the Potsdam City Palace. The original Baroque palace was constructed in 1669 under Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm, and was rebuilt under Friedrich II from 1744 to 1752, who performed additional interior decoration.

Sanssouci Palace, Potsdam – Architectural Detail

Potsdam and Sans Souci

In 1745, Frederick the Great arranged for the construction of a summer house in Potsdam. He had made quite specific sketches of what he desired, and had Knobelsdorff take care of the realization. They specified a single storey building resting on the ground of the vineyard terraces on the southern slope of the Bornstedt Heights in northwest Potsdam. Knobelsdorff raised objections to this idea; he wanted to increase the height of the building by adding a souterrain level to serve as a pedestal, plus a basement, and to move it forward to the edge of the terraces since it would otherwise look as if it had sunk into the ground if viewed from the foot of the vineyard hill. Frederick however insisted on his version. Even the suggestion that his plan increased the possibility of suffering from gout and catching cold did not cause Frederick to change his mind. Later he ran into these very difficulties, but bore them without complaint. Because of a disagreement about the site of the palace in the park, Knobelsdorff was fired in 1746. Jan Bouman, a Dutch architect, finished the project. After only two years of construction, Sans souci Palace (“my little vineyard house” was how Frederick referred to it) was dedicated on May 1, 1747. The palace’s name Sans souci translates as “without concerns”, meaning “without worries” or “carefree”, symbolizing that the palace was a place for relaxation rather than a seat of power. Frederick the Great usually resided there from May to September; the winter months he spent in the Potsdam City Palace.

The End

In 1753 Knobelsdorff’s long-time liver disease became more troublesome. A journey to the Belgian therapeutic baths at Spa brought no relief. Knobelsdorff died on September 16, 1753. Two days later the Berlinische Nachrichten reported, “On the 16th of this month the honorable gentleman, Mr. George Wentzel, Baron of Knobelsdorff, artistic director of all royal palaces, houses and gardens, director-in-chief of all construction in all provinces, as well as finance, war and domain councillor, departed this life after a prolonged illness in the 53rd year of his renowned existence.“

Potsdam – Schloss Sanssouci | Hin & weg, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Frederick the Great and the Potato, SciHi blog, March 24, 2013.

- [2] Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff at WikiCommons

- [3] Knobelsdorff, Georg Wenceslaus von. In: Ostdeutsche Biografie (Kulturportal West-Ost)

- [4] Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff. In: archINFORM.

- [5] Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff at German Digital Library

- [6] „Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff“ im Portal SPK digital der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz

- [7] Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff at Wikidata

- [8] Potsdam – Schloss Sanssouci | Hin & weg, DW Deutsch @ youtube

- [9] Map with Buildings by Knobelsdorff, via Wikidata