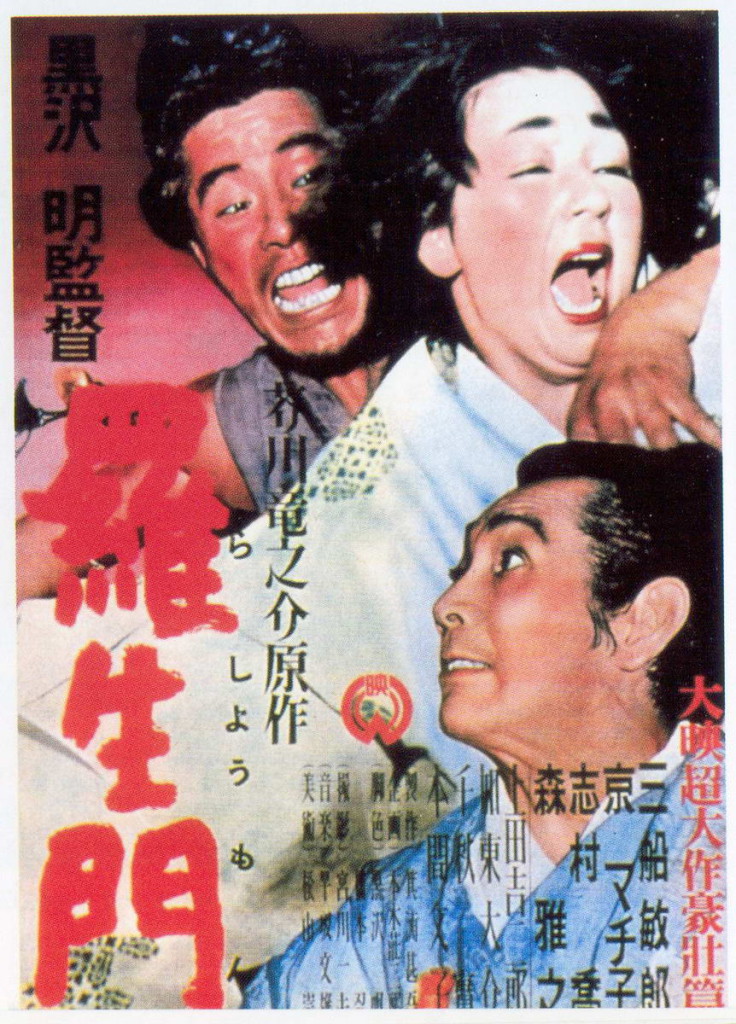

Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950)

On August 25, 1950, Akira Kurosawa‘s film Rashomon premiered. Rashomon marked the entrance of Japanese film onto the world stage. It won several awards, including the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1951, and an Academy Honorary Award at the 24th Academy Awards in 1952, and is now considered one of the greatest films ever made.

So, what is so special about this movie and what is the “Rashomon effect”?

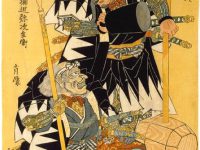

The film is based on two stories by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa: “Rashomon“, which provides the setting, and “In a Grove“, which provides the characters and plot. And what makes the plot of the film so special is that it involves various characters providing alternative, self-serving and contradictory versions of the same incident. Akira Kurosawa was born in 1910 and entered the Japanese film industry already in 1936, following a brief stint as a painter. He made his debut as a director in 1943, during World War II, with the popular action film Sanshiro Sugata. After the war, the critically acclaimed Drunken Angel (1948), in which Kurosawa cast then-unknown actor Toshiro Mifune in a starring role, cemented the director‘s reputation as one of the most important young filmmakers in Japan. However, it would be Kurosawa‘s second film of 1950, Rashomon, that would ultimately win him a whole new international audience.

“No one tells a lie after he’s said he’s going to tell one.” (The Commoner, from Rashomon)

It was based on Ryūnosuke Akutagawa‘s experimental short story In a Grove, which recounts the murder of a samurai and the rape of his wife from various different and conflicting points-of-view. The film opens on a woodcutter and a priest sitting beneath the Rajōmon city gate to stay dry in a downpour. A commoner joins them and they tell him that they have witnessed a disturbing story, which they then begin recounting to him. The woodcutter claims he found the body of a murdered samurai three days earlier while looking for wood in the forest; upon discovering the body, he says, he fled in a panic to notify the authorities. The priest says that he saw the samurai with his wife traveling the same day the murder happened. Both men were then summoned to testify in court, where they met the captured bandit Tajōmaru, who claimed responsibility for killing the samurai and raping his wife. It is human nature to listen to witnesses and decide who is telling the truth, but the first words of the screenplay, spoken by the woodcutter, are “I just don’t understand.” His problem is that he has heard the same events described by all three participants in three different ways–and all three claim to be the killer.[1]

The film left many critics puzzled by its unique theme and treatment

Shooting of Rashomon began on July 7, 1950 and, after extensive location work in the primeval forest of Nara, wrapped on August 17. Just one week was spent in hurried post-production, hampered by a studio fire, and the finished film premiered at Tokyo’s Imperial Theatre on August 25, expanding nationwide the following day. The movie was met by lukewarm reviews, with many critics puzzled by its unique theme and treatment, but it was nevertheless a moderate financial success for the studio.

Marge: Come on, Homer. Japan will be fun! You liked Rashomon.

Homer: That’s not how I remember it!

— The Simpsons, “Thirty Minutes over Tokyo”

The film appeared at the 1951 Venice Film Festival at the behest of an Italian language teacher, Giuliana Stramigioli, who had recommended it to Italian film promotion agency Unitalia Film seeking a Japanese film to screen at the festival. However, Daiei Motion Picture Company (a producer of popular features at the time) and the Japanese government had disagreed with the choice of Kurosawa’s work on the grounds that it was “not [representative enough] of the Japanese movie industry” and felt that a work of Yasujirō Ozu would have been more illustrative of excellence in Japanese cinema. Despite these reservations, the film was screened at the festival and won both the Italian Critics Award and the Golden Lion award—introducing western audiences, including western directors, more noticeably to both Kurosawa’s films and techniques, such as shooting directly into the sun and using mirrors to reflect sunlight onto the actor’s faces.

“Human beings are unable to be honest with themselves about themselves. They cannot talk about themselves without embellishing.” (Akira Kurosawa)

When Rashomon played in Venice and then went into international distribution, it stunned audiences. No one had ever seen a film quite like this one. For one thing, its daring, nonlinear approach to narrative shows the details of the crime as they are related, through the flashbacks of those involved.[5] The stories told in Rashomon are mutually contradictory and even the final version can be seen as motivated by factors of ego and face. During filming, the actors kept approaching Kurosawa wanting to know the truth, and he claimed the point of the film was be to be an exploration of multiple realities rather than an exposition of a particular truth. The idea of contradicting interpretations has been around for a long time. It is studied in the context of understanding the nature of truth(s) and truth-telling. The term “Rashomon effect” refers to real-world situations in which multiple eye-witness testimonies of an event contain conflicting information. Brimming with action while incisively examining the nature of truth, “Rashomon” is perhaps the finest film ever to investigate the philosophy of justice.

The genius of Rashomon

The genius of Rashomon is that all of the flashbacks are both true and false. True, in that they present an accurate portrait of what each witness thinks happened. False, because as Kurosawa observes in his autobiography, “Human beings are unable to be honest with themselves about themselves. They cannot talk about themselves without embellishing.”[1] The cinematographer, Kazuo Miyagawa, contributed numerous ideas, technical skill and expertise in support for what would be an experimental and influential approach to cinematography. Rashomon had camera shots that were directly into the sun. Kurosawa wanted to use natural light, but it was too weak; they solved the problem by using a mirror to reflect the natural light. The result makes the strong sunlight look as though it has traveled through the branches, hitting the actors.

Kurosawa influences on today’s cinema are indisputable. Besides other influential movies, Rashomon is the clear source for the structures of movies like “Reservoir Dogs,” “Vantage Point,” “Hero”, or most of all Bryan Singer’s “The Usual Suspects”, because of its address and skepticism of the trustworthiness of witness accounts, whether first-person or relayed by a second party.

David Thorburn, 22. Kurosawa and Rashomon, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Rashomon at RogerEbert.com

- [2] Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (video) at the Internet Archive

- [3] Rashomon at the Internet Movie Database

- [4] Pictures Always Lie: Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon

- [5] Stephen Prince: The Rashomon Effect

- [6] Rashomon at Wikidata

- [7] Akira Kurosawa at Wikidata

- [8] David Thorburn, 22. Kurosawa and Rashomon, MIT 21L.011 The Film Experience, Fall 2013, MIT OpenCourseWare @ youtube

- [9] Burch, Nöel (1979). To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema. University of California Press.

- [10] Galbraith, Stuart, IV (2002). The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. Faber and Faber, Inc.

- [11] Heider, Karl G. (March 1988). “The Rashomon Effect: When Ethnographers Disagree”. American Anthropologist. 90 (1): 73–81.

- [12] Timeline for Akira Kurosawa, via Wikidata