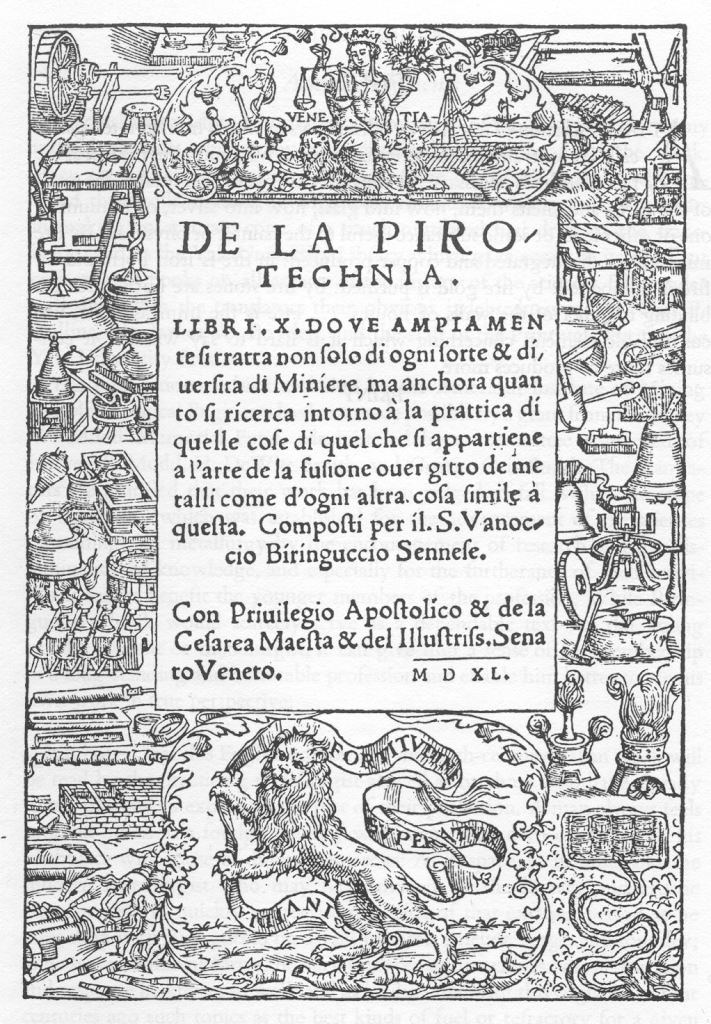

De la Pirotechnia (1540) by Vannoccio Biringuccio

Probably on October 20, 1480, Italian matallurgist Vannoccio Biringuccio was born. He is best known for his manual on metalworking, De la pirotechnia, published posthumously in 1540. Biringuccio is considered by some as the father of the foundry industry.

Vannoccio Biringuccio – Early Years

Biringuccio was born in Siena to Paolo Biringuccio, thought to have been an architect and public servant, and his mother was Lucrezia di Bartolommeo Biringuccio. He was baptised on October 20, 1480. Thus, he might have been born the day before. He was a follower of Pandolfo Petrucci, the head of the powerful Petrucci family, the rulers of the Italian city of Siena. As a young man Biringuccio was travelling in Italy as well as in Germany inspecting metallurgical operations. After running an iron mine and forge at Boccheggiano for Pandolfo Petrucci, he was appointed to a post with the arsenal at Siena and in 1513 directed the mint. When Pandolfo died, Biringuccio remained tied to the Petrucci family, being employed by Pandolfo’s son Borghese Petrucci. However, the uprising of 1515 forced Borghese to flee from Siena, taking Biringuccio with him. Biringuccio traveled about Italy, and visited Sicily in 1517.

Return from Exile

In 1523 Pope Clement VII caused the reinstatement of the Petrucci family, and along with them Biringuccio was able to return from exile. In 1524 he was granted a monopoly on the production of saltpeter across all of Siena. However, this was short lived — already in 1526, the people of Siena revolted and threw the Petrucci family out again. Although, the family made an attempt aided by Biringuccio to regain Siena by force, but it failed. Thereafter Biringuccio served the Venetian and Florentine republics, and cast cannon and built fortifications for the Este and Farnese families.

The Duomo

In 1530, Siena entered a more peaceful phase, and Biringuccio returned, time in honor, as senator and, succeeding Baldassare Peruzzi, as architect and director of building construction at the Duomo. In 1538 he became head of the papal foundry in Rome, and director of munitions. His exact place and date of death is unknown; all that is known is that a document dated 1539 mentions his death.

On Metalwork

The reason for Biringuccio’s fame is certainly the publication of his manual on metalworking, De la pirotechnia, published posthumously in 1540. Thus, Biringuccio is considered by some as the father of the foundry industry as De la pirotechnia is the first printed account of proper foundry practice. It also gives details of mining practice, the extraction and refining of numerous metals, alloys such as brass, and compounds used in foundries and explosives. It preceded the printing of De re metallica by Georg Agricola by more than a decade. Moreover, Agricola’s famed sections on glass, steel, and the purification of salts by crystallization are in fact taken nearly verbatim from the Pirotechnia. The work is one of earliest technical manuscripts to survive from the Renaissance, and is thus a valuable source of information on technical practice at the time of writing. The work was printed in 1540 in Venice, and has been reprinted numerous times [2].

Renaissance Art History

Biringuccio is also important in art history for his description of the peculiarly Renaissance arts of casting medallions, statues, statuettes, and bells. His account of typecasting, given in considerable detail, is the earliest known. The Pirotechnia contains eighty-three woodcuts, the most useful being those depicting furnaces for distillation, bellows mechanisms, and devices for boring cannon and drawing wire.[2]

Strong Winds and Rockets

A member of Fraternita di Santa Barbara guild, before his book information on metallurgy and military arts were closely held secrets. In fact, his book is credited with starting the tradition of scientific and technical literature.[2] Also, Pirotechnia offers one of the first written attempts to explain what causes a rocket to move. Biringuccio attributed the propulsive force to a “strong wind”:

One part of fire takes up as much space as ten parts of air, and one part of air takes up the space of ten parts of water, and one part of water as much as ten parts of earth. Now sulfur is earth, consisting of the four elementary principles, and when the sulfur conducts the fire into the driest part of the powder, fire, and air increase … the other elements also gird themselves for battle with each other and the rage of battle is changed by their heat and moisture into a strong wind. (Vannoccio Biringuccio, De la Pirotechnia, 1540)

As a practitioner, Biringuccio presented all technical processes clearly and used his native language to address not only scholars. It was the first ever book on metallurgy and remained the unsurpassed standard work for over two centuries. It also offered the first detailed account of flame furnaces and the hardening of antimony; the first mention of the increase in weight when lead is calcined in flame furnaces; the first description of the change in color when steel is hardened, which only Robert Boyle [4] made more precise; the first mention of manganese under these modern names.

Paula Findlen, How the Renaissance Began [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Vannoccio Biringuccio at Britannica

- [2] Vannoccio Biringuccio at Encyclopedia.com

- [3] Vannoccio Biringuccio’s De la Pirotechnia at the Corning Museum of Glass

- [4] Robert Boyle – The Sceptical Chemist, SciHi Blog

- [5] Works by or abot Vannoccio Biringuccio at German National Library

- [6] Vannoccio Biringuccio (January 1990). The Pirotechnia of Vannoccio Biringuccio (in Italian). Cyril Stanley Smith, Martha Teach Gnudi (trans.). Dover.

- [7] Vannoccio Biringuccio at Wikidata

- [8] Paula Findlen, How the Renaissance Began, Stanford @ youtube

- [9] Smith, C.S. (1970–1980). “Biringuccio, Vannoccio”. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 142–143.

- [10] Timeline of Foundrymen, via Wikidata and DBpedia