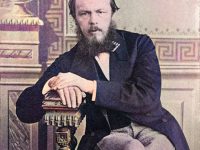

David Abelevich Kaufman, aka Dziga Vertov (1896 – 1954)

On January 2, 1898, Soviet pioneer documentary film and newsreel director, as well as a cinema theorist Dziga Vertov was born. He is considered one of the most important early directors of documentary films because of both his experimental work and his theoretical texts. Vertov was a brother of the later Hollywood cinematographer and Oscar winner Boris Kaufman and the cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman, with whom he collaborated, for example in his most famous film The Man with a Movie Camera.

“I’m an eye. A mechanical eye. I, the machine, show you a world the way only I can see it. I free myself for today and forever from human immobility. I’m in constant movement. I approach and pull away from objects. I creep under them.”

― Dziga Vertov

Becoming Dziga Vertov

Vertov was born David Abelevich Kaufman, the oldest of three siblings, into a Jewish family in Białystok, Poland, then a part of the Russian Empire.Prior to his family’s flight from the invading German Army to Moscow in 1915, Vertov studied music at the Białystok Conservatory. After settling in Petrograd, Vertov began to write poetry, science fiction, and satire. From 1916 to 1917, he attended the Psychoneurological Institute in Saint Petersburg to study medicine and also experimented with creating “sound collages” in his spare time. He Russified his Jewish name and patronymic, David Abelevich, to Denis Arkadievich at some point after 1918. Later he adopted the name “Dziga Vertov,” which translates loosely from Ukrainian as “spinning top.”

The Moscow Cinema Committee

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, Vertov, at the age of 22, started working as an editor for “Kino-Nedelya,” the Moscow Cinema Committee’s weekly film series and Russia’s first newsreel series. It was launched in June 1918. While working on “Kino-Nedelya,” Vertov met his future wife, film director and editor Elizaveta Svilova, who was working as an editor at Goskino at the time. His brother, Mikhail Kaufman, served as cameraman.

The Agit-Trains

Vertov worked on the “Kino-Nedelya” series for three years and helped establish and run a film car on Mikhail Kalinin‘s agit-train during the Russian Civil War between Communists and counterrevolutionaries. The agit-trains were equipped with various resources, such as actors for live performances or printing presses, and Vertov’s film car had equipment for shooting, developing, editing, and projecting film. These trains were sent on agitation-propaganda missions to the battlefronts to boost the morale of the troops and also to stir up revolutionary fervor among the masses.

Documentaries

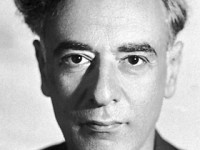

In 1919, Vertov compiled newsreel footage for his documentary “Anniversary of the Revolution” and supervised the filming of “The Battle for Tsaritsyn” in the same year. He also compiled “History of the Civil War” in 1921. The “Council of Three,” a group that issued manifestoes in the radical Russian newsmagazine “LEF,” was formed in 1922 and consisted of Vertov, his future wife and editor Elizaveta Svilova, and his brother and cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman. Vertov’s fascination with machinery led to a curiosity about the mechanical aspects of cinema.

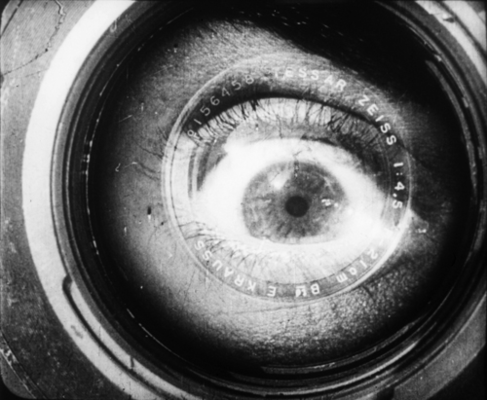

In this shot, Mikhail Kaufman acts as a cameraman risking his life in search of the best shot

Forced Glorification

Vertov used film montage, like his contemporary Sergei Eisenstein,[1] to influence the audience of his films. However, his experimental style ultimately led to the end of his artistic career when Socialist Realism became the required principle in cinematography, especially for film documentarists who also had to show loyalty to the personality cult surrounding Stalin. As a result, in 1934, Vertov was forced to glorify Lenin in the film “Three Songs about Lenin” on Stalin’s orders.

Still from Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera.

The Man with a Movie Camera

His most famous film, “The Man with a Movie Camera,” celebrates urban life in Soviet cities and the mechanization of life, but also focuses on the process of making the film from the camera lens to the editing room. Vertov’s feature film was produced by the All-Ukrainian Photo Cinema Administration (VUFKU) and explores life in Moscow, Kyiv, and Odesa during the late 1920s. The film has no actors and instead portrays the daily lives of Soviet citizens at work and leisure, as well as their interactions with the technology and infrastructure of modern life. The film’s main characters are the cameramen, film editor, and the Soviet Union itself, which are depicted through a variety of cinematic techniques such as multiple exposure, fast motion, slow motion, freeze frames, match cuts, jump cuts, split screens, Dutch angles, extreme close-ups, tracking shots, reversed footage, stop motion animations, and self-reflexive visuals. This film has been recognized as a precursor to Godfrey Reggio’s “Koyaanisqatsi” due to its similarities in content and style.

Man with a Movie Camera was largely dismissed upon its initial release; the work’s fast cutting, self-reflexivity, and emphasis on form over content were all subjects of criticism. In the British Film Institute’s 2012 Sight & Sound poll, however, film critics voted it the 8th greatest film ever made, the 9th greatest in the 2022 poll, and in 2014 it was named the best documentary of all time in the same magazine. The National Oleksandr Dovzhenko Film Centre placed it in 2021 at number three of their list of the 100 best films in the history of Ukrainian cinema.

Later Years

Vertov’s successful career continued into the 1930s. Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass (1931), an examination into Soviet miners, has been called a ‘sound film’, with sound recorded on location, and these mechanical sounds woven together, producing a symphony-like effect. Dziga Vertov died of cancer in Moscow in 1954.

Legacy

Beginning in the late 1960s, Dziga Vertov’s work was rediscovered by aesthetically and politically radical artists. Leading the way here was Jean-Luc Godard, who gave up his individual activity as a director at the end of the 1960s and made films only in the programmatically named collective of the Groupe Dziga-Vertov until the 1970s.

Kino Eye (1924), [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Sergei Eisenstein and the Art of Montage, SciHi Blog

- [2] Cook, Simon. “Our Eyes, Spinning Like Propellers: Wheel of Life, Curve of Velocities, and Dziga Vertov’s Theory of the Interva l.” October, 2007: 79–91.

- [3] Feldman, Seth. “‘Peace between Man and Machine’: Dziga Vertov’s The Man with a Movie Camera.” in: Barry Keith Grant, and Jeannette Sloniowski, eds. Documenting the Documentary: Close Readings of Documentary Film and Video. Wayne State University Press, 1998. pp. 40–53.

- [4] Hicks, Jeremy. Dziga Vertov: Defining Documentary Film. London & New York: I. B. Tauris, 2007.

- [5] Dziga Vertov at IMDb

- [6] Kino Eye (1924), scored by Robert Israel in 1999 on YouTube

- [7] Christophe Le Choismier: Dziga Vertov: The Masters Series Videoartworld.

- [8] Manovich, Lev. “Database as a Symbolic Form”. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001.

- [9] Man with a Movie Camera is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- [10] Timeline of Soviet Cinematographers, via DBpedia and Wikidata