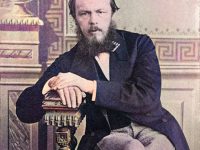

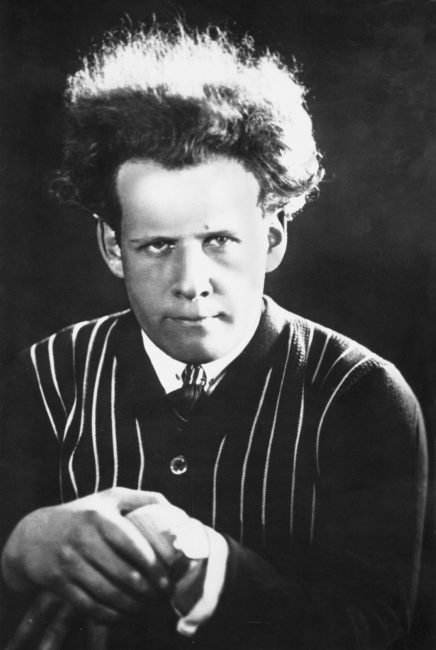

Sergei Eisenstein (1898-1948)

On January 22, 1898, Soviet film director and film theorist Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein was born. Eisenstein is considered a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. He is noted in particular for his silent films Strike (1925), Battleship Potemkin (1925) and October (1928), as well as the historical epics Alexander Nevsky (1938) and Ivan the Terrible (1944, 1958).

“American capitalism finds its sharpest and most expressive reflection in the American cinema.”

— Sergei Eisenstein [4]

Early Years

Sergei Michailowitsch Eisenstein was born in Riga, Russian Empire, the son of Riga city architect and state councillor Michail Eisenstein, who built Art Nouveau buildings in the centre of Riga, and his wife Julia Konezkaja. Eisenstein, who grew up in upper middle-class circumstances, studied at the Petrograd Institute for Civil Engineers. But he soon noticed that theatre was his great passion. In 1918 he was called to the Red Army and worked as a cartoonist for an agitprop procession. In 1920 he changed to the army theater, but in the same year he was delegated to Moscow to study the Japanese language. He broke this off and entered the Proletkult Theatre as a stage designer. There he took part in directing courses of the extreme theatre innovator Wsewolod Meyerhold.In 1923 Eisenstein began his career as a theorist, by writing “The Montage of Attractions” for art journal LEF. Eisenstein’s first film, Glumov’s Diary was also made in that same year with Dziga Vertov hired initially as an “instructor”

From Theatre to Cinema

He continued his artistic career and gained film experiences which he used in stage work. With the concept of the attraction montage he founded first theoretically, then in his films the attempt of an independent, revolutionary art form. In 1929 he began to study the new film technique, and in order to earn money he made two films abroad (Frauennot-Frauenglück, La Romance sentimentale). At the invitation of Paramount he went to Hollywood and gave lectures at the biggest universities of Europe and the USA. Later he taught at the Moscow Film Academy and wrote several books.

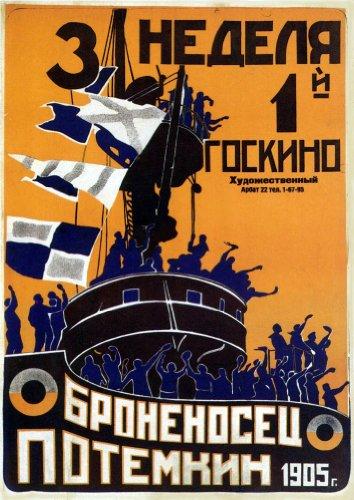

Battleship Potemkin, original movie poster (1926)

Battleship Potemkin

Strike (1925) was Eisenstein’s first full-length feature film. Battleship Potemkin (1925) was acclaimed critically worldwide. It presents a dramatized version of the mutiny that occurred in 1905 when the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkin rebelled against their officers. In the film the rebels raise the red flag on the battleship but the Orthochromatic B/W film stock of that period made a red flag look black so a white flag was used instead. This was handtinted red for 108 frames by Eisenstein himself for the premiere at the Grand Theatre, which was greeted with thunderous applause by the Bolshevik audience. Eisenstein wrote the film as a revolutionary propaganda film, but also used it to test his theories of montage. The revolutionary Soviet filmmakers of the Kuleshov school of filmmaking were experimenting with the effect of film editing on audiences, and Eisenstein attempted to edit the film in such a way as to produce the greatest emotional response, so that the viewer would feel sympathy for the rebellious sailors of the Battleship Potemkin and hatred for their overlords. In the manner of most propaganda, the characterization is simple, so that the audience could clearly see with whom they should sympathize. Battleship Potemkin has received universal acclaim from modern critics. Directors Billy Wilder and Charlie Chaplin both named Battleship Potemkin as their all-time favourite film.

The Art of Montage

One of his most striking contributions was the development of the montage and a new method of cutting and mounting film after “shooting” was over to produce a rapid panoramic progression of images that forcefully projected some idea. “A work of art understood dynamically is just the process of arranging images and feelings in the mind of the spectator,” he wrote.[5] He and his contemporary, Lev Kuleshov, two of the earliest film theorists, argued that montage was the essence of the cinema. His articles and books – particularly Film Form (1942) and The Film Sense (1949) – explain the significance of montage in detail. Eisenstein believed that editing could be used for more than just expounding a scene or moment, through a “linkage” of related images. Eisenstein felt the “collision” of shots could be used to manipulate the emotions of the audience and create film metaphors. He believed that an idea should be derived from the juxtaposition of two independent shots, bringing an element of collage into film.

Art vs Politics

In 1928, Eisenstein finished his work on October, a celebratory dramatization of the 1917 October Revolution commissioned for the tenth anniversary of the event. Originally released as October in the Soviet Union, the film was re-edited and released internationally as Ten Days That Shook The World, after John Reed‘s popular book on the Revolution. Eisenstein’s montage experiments met with official disapproval; the authorities complained that October was unintelligible to the masses, and Eisenstein was attacked—for neither the first time nor the last—for excessive “formalism”. From 1934 Eisenstein was married to the journalist and film critic Pera Ataschewa (1900-1965).

In his initial films, Eisenstein did not use professional actors. His narratives eschewed individual characters and addressed broad social issues, especially class conflict. He used stock characters, and the roles were filled with untrained people from the appropriate classes; he avoided casting stars. Eisenstein’s vision of communism brought him into conflict with officials in the ruling regime of Joseph Stalin. Like many Bolshevik artists, Eisenstein envisioned a new society which would subsidize artists totally freeing them from the confines of bosses and budgets, leaving them absolutely free to create, but budgets and producers were as significant to the Soviet film industry as the rest of the world.

Collaboration with Sergei Prokoviev

During the Stalin purges in 1937/38 the secret police NKWD prepared a show trial with him as the accused, but the trial did not take place. The files were discovered in the 1990s. Eisenstein worked with the Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev on two of his films: Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible (Part I and Part II), the latter presenting Ivan IV of Russia as a national hero and planned as a three-part film, but Eisenstein was only able to complete the first two parts. While the first part of Ivan the Terrible was awarded the Stalin Prize in 1945, the second part was forbidden to be performed because of the insufficiently linear implementation of Soviet historical images. Stalin himself demanded “post-production”. Together with Prime Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, Stalin Eisenstein gave concrete instructions. He criticised Eisenstein for depicting the tsar as an undecided ruler like Hamlet. Moreover, Opritschnina was not shown as a “progressive force”. All footage from the still incomplete Ivan The Terrible, Part III was confiscated, and most of it was destroyed, though several filmed scenes exist

On February 11, 1948, Sergei Eisenstein died of a heart attack while working on a text on the history of Soviet film. His numerous writings on film theory were only published in part from the 1960s onwards, as were his memoirs.

Sergei Eisenstein, The Battleship Potemkin, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Billy Wilder and Hollywood’s Golden Age, SciHi Blog

- [2] Battleship Potemkin on IMDb

- [3] Battleship Potemkin at the Internet Archive

- [4] Sergei Eisenstein, Film form [and]: The film sense; two complete and unabridged works. (1957)

- [5] Sergei Eisenstein Is Dead In Moscow; Obituary, New York Times, February 12, 1948

- [6] October: Ten Days That Shook the World, released on official Mosfilm YouTubechannel, with subtitles in English

- [7] Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein Collection at the Museum of Modern Art Museum Archives.

- [8] Sergei Eisenstein at Wikidata

- [9] Sergei Eisenstein, The Battleship Potemkin, FSUE Mosfilm cinema concern @ youtube

- [10] Bergan, Ronald (1999), Sergei Eisenstein: A Life in Conflict, Boston, MA: Overlook Hardcover

- [11] Seton, Marie (1952), Sergei M. Eisenstein: A Biography, New York: A.A. Wyn

- [12] Timeline for Sergei Eisenstein, via Wikidata