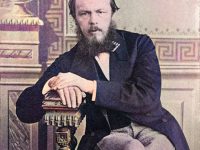

Dimitri Shostakovich (1906 – 1975)

On 25 September 1906, Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist Dmitri Shostakovich was born. He became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throughout his life as a major composer. In addition to 15 symphonies, instrumental concertos, stage works and film music, he composed 15 string quartets, which are among the major works of the 20th century chamber music repertoire.

“I live in the USSR, work actively and count naturally on the worker and peasant spectator. If I am not comprehensible to them I should be deported.”

– Dimitri Schostakovich, In discussion with an opera audience, January 14, 1930 [7]

Dmitri Shostakovich – Youth and Education

Dmitri Shostakovich was born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, being the second of Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich, an engineer, and his wife Sofia Kokulina. Despite the musical tradition in the family, the son was at first hardly interested in music; however, his mother was soon able to direct the interests of Dmitri to the piano. The boy’s musical talent unfolded through piano lessons, and Dmitri soon made his first compositional attempts. In 1917, the eleven-year-old witnessed a worker being shot by policemen during a demonstration. Mitja then composed a hymn to freedom and a funeral march for the victims of the revolution.

Because his piano teacher could teach him nothing more, Shostakovich began to study piano with Leonid Nikolaev and composition with Maximilian Steinberg at the Petrograd Conservatory (the name of Saint Petersburg from 1914 to 1924) in 1919. By early 1923, a year after his father’s death, the family was nearly ruined due to the economic and political uncertainty of the post-revolutionary period. In addition, Shostakovich, who had always had poor health, was diagnosed with pulmonary and lymphatic tuberculosis. This ailment accompanied and shaped him throughout his life.

First Success

“There can be no music without ideology. The old composers, whether they knew it or not, were upholding a political theory. Most of them, of course, were bolstering the rule of the upper classes. Only Beethoven was a forerunner of the revolutionary movement. If you read his letters, you will see how often he wrote to his friends that he wished to give new ideas to the public and rouse it to revolt against its masters.”

– Dimitri Schostakovich, New York Times, December 20, 1931.

The sensational success of his 1st Symphony in F minor in 1925 earned Shostakovich a degree from the conservatory and worldwide recognition at the age of only nineteen. At the first performance of this symphony, written as a thesis, the second movement was played again as an encore after an overwhelming applause. A year later Bruno Walter conducted the symphony in Berlin, and performances in America under Leopold Stokowski and Arturo Toscanini followed. The composer Alban Berg wrote Shostakovich a letter of congratulations.

In the period that followed, Dmitri Shostakovich explored various contemporary musical styles such as futurism, atonality, and symbolism, but followed a path all his own. His music is a blend of convention and revolution, grounded in sound compositional craftsmanship and featuring imaginative orchestration and modern melodic and harmonic writing. He was inspired by the works of contemporary composers such as Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Prokofiev, and increasingly by the works of Gustav Mahler from 1930 onward.[1]

Shostakovich was commissioned in March 1927 to write a kind of anthem for the celebrations of the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution. In response, during the summer he composed the 2nd Symphony “To October” in B major, one of his most avant-garde compositions of the period. With this symphony, however, Shostakovich took the musical path of a propagandistic commissioned composer for the Soviet government, which was the only possible path for him, but which was misunderstood by Western music critics for a long time. But behind the apparent concessions to the Stalinist regime, Shostakovich hid in many places a mixture of mockery, sarcasm and criticism of the political and social conditions.

Compositions Under Stalin

“I feel eternal pain for those who were killed by Hitler, but I feel no less pain for those killed on Stalin’s orders. I suffer for everyone who was tortured, shot, or starved to death.”

– Dimitri Schostakovich, Testimony (1979)

After Shostakovich’s first opera, The Nose (based on Gogol’s tale of the same name), a satire on Russian bureaucracy that contains the first long percussion solo in European music and about which contemporary composers such as György Ligeti expressed their admiration, disappeared from the stages after 16 performances, the composer began his second opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, a work that was to cause a great deal of turmoil. The premiere in Leningrad in January 1934 was a tremendous success. Shostakovich’s popularity and fame increased; he was acclaimed by critics and audiences alike.

Two years after the premiere, Stalin attended the performance of the opera at the Bolshoi Theater together with Molotov, Mikoyan, and Zhdanov. Stalin sat, hidden behind a curtain, in the government box, right above the orchestra pit. The box was shielded with steel plates to prevent possible assassination attempts. The amplified brass trumpeted directly into his ears. It is alleged that Stalin rose wordlessly during the opera and left the theater without having received Shostakovich in his box. This reaction was almost tantamount to an execution in the climate of permanent fear of falling from grace at the time. “This is silly stuff, not music,” Stalin told Izvestia’s music correspondent.

4th, 5th, and 7th Symphony

“Real music is always revolutionary, for it cements the ranks of the people; it arouses them and leads them onward.”

– Dimitri Schostakovich, The Power of Music (1964)

After withdrawing his Symphony No. 4 in C minor and letting it disappear into a drawer because of the critical Pravda article, Shostakovich began work on his moderate Symphony No. 5 in D minor in the Crimea in April 1937, under the official slogan of “a Soviet artist’s practical response to just criticism.” Back in Leningrad, he learned that his sister’s husband had been arrested and that she herself had been deported to Siberia. After the premiere, the 5th Symphony was officially presented as the return of the prodigal son to the cultural policy loyal to the line. The work became a great international success, and for a long time the march finale was considered a glorification of the regime. Shostakovich’s memoirs, disputed in their authenticity, claim that the Triumphal March is in fact a death march. The 7th Symphony in C major takes this doctrine even further and is considered Shostakovich’s best known work. The work was composed in 1941 at the time of the siege of Leningrad by Hitler’s troops, while Shostakovich was assigned to the fire department and worked on his piece under shellfire. In October 1941 Shostakovich and his family were flown out of Leningrad and were able to complete the symphony in Kuibyshev (Samara). The Moscow premiere on March 27, 1942, took place under life-threatening circumstances, but even an air alert could not persuade the audience to seek shelter. Stalin was interested in making the symphony known outside the Soviet Union as a symbol of heroic resistance to fascism. His wish for a performance in Leningrad was fulfilled a short time later: a special plane broke through the air blockade to fly the orchestral score to Leningrad. The concert was broadcast by all Soviet radio stations. Shostakovich received the Stalin Prize for his work because it was perceived as a tribute to the will to resist of the starving population trapped by German troops.

Again the Critics

“A creative artist works on his next composition because he is not satisfied with his previous one. When he loses a critical attitude toward his own work, he ceases to be an artist.”

– Dimitri Schostakovich, New York Times, October 25, 1959.

The epic 8th Symphony in C minor, premiered in Moscow in 1943 under Yevgeny Mravinsky and often referred to as the “Stalingrad Symphony,” was also written under the impact of wartime events. In its humanistic commitment, the symphony avoids grand heroic gestures. After the war, the 8th Symphony fell victim to censorship; it was no longer performed, and even many radio recordings were deleted. After the end of the Second World War, which had been won, the music world expected a triumphant symphony – in the style of Beethoven’s Ninth, for example. But Shostakovich once again failed Soviet critics with his 9th Symphony in E-flat Major, for it is instead a work of almost Haydnian simplicity, ending with grotesque “circus music” – far from a grandiose finale. In the struggle against “formalism,” Shostakovich, though awarded several Stalin prizes, found himself under fierce attack, especially after 1948. By now a famous and respected composer worldwide, Shostakovich again found himself in the position in the Soviet Union of being constantly caught between the threat of arrest on the one hand and awards for his work on the other.

Poststalinism and later Life

In 1953 Stalin died, and Shostakovich published his 10th Symphony in E minor, his reckoning with the dictator. It is a work of sorrow and pain, but it ends with a gesture of personal triumph and self-assertion. This was followed in 1957 by the 11th Symphony in G minor, subtitled “The Year 1905.” 1905 refers to St. Petersburg’s Bloody Sunday, when the tsar ordered the shooting of an unarmed crowd who wanted to petition him. On June 8, 1958, a resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party was published rehabilitating Shostakovich, Khachaturian, the late Prokofiev, and other composers, and withdrawing previous criticism of a 1948 decree. He was allowed to leave the Soviet Union again and accepted the invitation of the GDR government to compose the film music for the film Five Days – Five Nights.

In the mid-1960s, illnesses became more frequent, and Shostakovich suffered from chronic inflammation of the spinal cord, which led to progressive paralysis of the right hand. In 1966 he suffered a first heart attack, and five years later a second. With his 13th Symphony in B-flat minor, Shostakovich again came under criticism because the work, set to words by the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, denounces Russian anti-Semitism. The 14th Symphony for soprano, bass, and chamber orchestra already dealt forcefully with the theme of death and farewell. In late 1967, Shostakovich broke his leg, and he remained disabled. Since then, he spent several months each year in hospitals and nursing homes. The 15th Symphony in A major, his last, is an enigmatic retrospective of a composer’s life full of ups and downs, filled with (self-)quotes, only friendly at first glance, rather abysmal.

Shostakovich died of a heart attack on August 9, 1975. Among the many wreaths that decorated the grave was one from the KGB.

Michael Parloff: Lecture on the Life and Music of Dmitri Shostakovich, [2]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Gustav Mahler and the Modernism in Music, SciHi Blog

- [2] Michael Parloff: Lecture on the Life and Music of Dmitri Shostakovich, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center @ youtube

- [3] Blokker, Roy (1979). The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich, the Symphonies. The great composers. Associated Univ Press.

- [4] Fay, Laurel (2000). Shostakovich: A Life. Oxford University Press

- [5] van Rijen, Onno. “Opus by Shostakovich”. Shostakovich & Other Soviet Composers.

- [6] “Discovering Shostakovich”. BBC Radio 3.

- [7] Fay, Laurel (2000). Shostakovich: A Life. Oxford University Press, p. 55.

- [8] Dimitri Shostakovich at Wikidata

- [9] Timeline for Dimitri Shostakovich, via Wikidata