Ambroise Paré (1510-1590)

On December 20, 1590, French barber surgeon Ambroise Paré passed away. He is considered one of the fathers of surgery and modern forensic pathology and a pioneer in surgical techniques and battlefield medicine, especially in the treatment of wounds. He was also an anatomist and invented several surgical instruments.

Ambroise Paré – Early Years

Paré was born in 1510 in Bourg-Hersent in north-western France. As a child he watched, and was first apprenticed to, his older brother, a barber-surgeon in Paris. He was also a pupil at Hôtel-Dieu, France’s oldest hospital. There, he was taught anatomy and surgery and in 1537 was employed as an army surgeon at Piedmont, during the campaign of Francis I. As many of his colleagues, Paré gained first experience as a result of war. At the time, surgeons treated gunshot wounds with boiling oil since such wounds were believed to be poisonous. When, one day, he was presented with more gunshot wounds than he had oil for, he improvised and used an old Roman technique, using oil of roses, egg white, and turpentine. He worried through the night that the soldiers would die, but to his surprise, he found the next morning that the soldiers treated with oil were in agony, their wounds swollen and some had even died during the night, whereas the men treated the Roman way were well rested, their wounds calm and beginning to heal.

Battlefield Surgery

Paré also rejected cautery to seal wounds after amputation. Instead, he used ligatures to tie off the blood vessels (first used by Galen)[4]. While this was less painful for the patient, the ligatures could cause infection, complications and death, so were not adopted as readily by other surgeons. His new technique was not perfect, as there was still a chance of infection and the pain was still a problem, but both of these were a much smaller problem than when using boiling oil. Sometime later he reported his findings in La Méthod de traicter les playes faites par les arquebuses et aultres bastons à feu (1545, “The Method of Treating Wounds Made by Harquebuses and Other Guns”), which was ridiculed because it was written in French rather than in Latin.

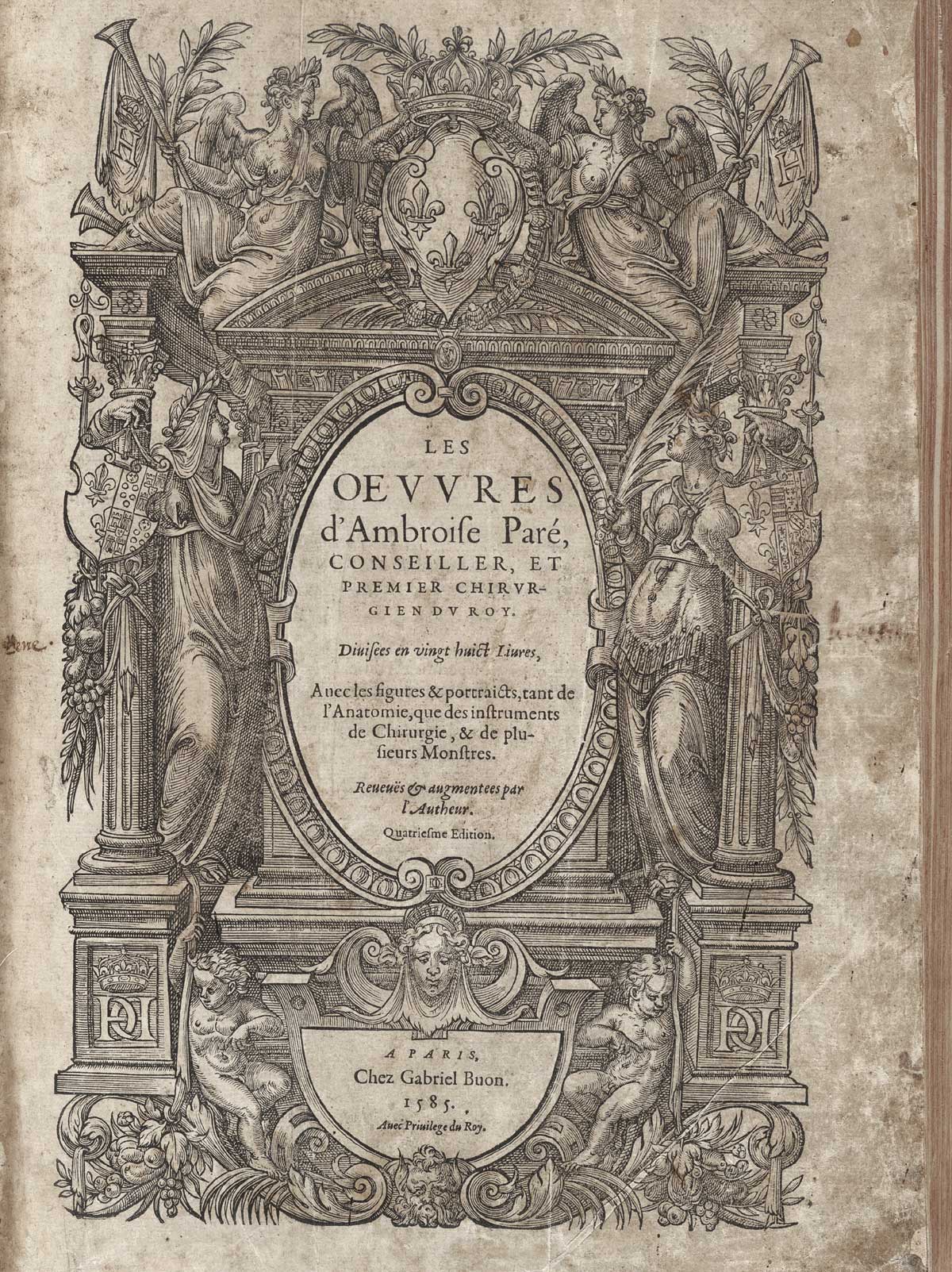

The title page of Ambroise Pare’s Oeuvres

The Phantom Amputation Limb

Paré was a keen observer and did not allow the beliefs of the day to supersede the evidence at hand. He spent his life serving in the army in wartime, and caring for the sick and poor of Paris during peaceful periods. During his work with injured soldiers, Paré documented the pain experienced by amputees which they perceive as sensation in the ‘phantom’ amputated limb. Paré believed that phantom pains occur in the brain and not in remnants of the limb. He designed mechanical prosthetics, illustrated in his Dix Livres de la Chirurgie (1564, Ten Books of Surgery) aimed at helping amputees return to a semblance of normalcy.[3] He was also interested in the application of new anatomical ideas – such as those of Andreas Vesalius – developed a number of instruments and artificial limbs, and introduced new ideas in obstetrics.[5,2] When Vesalius made strides in understanding human anatomy, Paré had parts of Vesalius’s work translated into French, making it available to barber-surgeons who couldn’t read Latin. [3] He revived the practice of podalic version, and showed how even in cases of head presentation, surgeons with this operation could often deliver the infant safely, instead of having to dismember the infant and extract the infant piece by piece.

“Pregnancy with 11 fetuses” Giovanni Pico della Mirandola reported the case of an Italian woman, Dorothea, who allegedly gave birth to undecaplets after having given birth to nonuplets, from Ambroise Paré ‘Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine‘

In the Royal Service

In 1552, Paré was accepted into royal service of the Valois Dynasty under Henry VI. He was however unable to cure the king’s fatal blow to the head, which he received during a tournament in 1559. In 1567, Paré described an experiment to test the properties of bezoar stones. At the time, the stones were commonly believed to be able to cure the effects of any poison, but Paré believed this to be impossible. It happened that a cook at Paré’s court was caught stealing fine silver cutlery, and was condemned to be hanged. The cook agreed to be poisoned, on the conditions that he would be given a bezoar straight after the poison and go free in case he survived. The stone did not cure him, and he died in agony seven hours after being poisoned. Thus Paré had proved that bezoars could not cure all poisons.

According to Henri IV‘s Prime Minister, Sully, Paré was a Huguenot and on 24 August 1572, the day of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, Paré’s life was saved when King Charles IX locked him in a clothes closet. Ambroise Paré died in Paris in 1590 from natural causes in his 80th year.

Getting Better: 200 Years of Medicine. NEJM, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Ambroise Paré at Encyclopedia Britannica

- [2] Ambroise Paré (1510-90) at Sciencemuseum.org

- [3] Ambroise Paré at StrangeScience

- [4] Galenus of Pergamon – The most Accomplished Physician of Antiquity, SciHi Blog

- [5] Andreas Vesalius and the Science of Anatomy, SciHi Blog

- [6] Stephen Paget (1897), Ambroise Paré and His Times, 1510–1590, G.P. Putnam’s sons.

- [7] Ambroise Paré at Wikidata

- [8] Getting Better: 200 Years of Medicine. NEJMvideo @ youtube

- [9] Paget, Stephen (1897). Ambroise Paré and his times, 1510-1590. G.P. Putnam’s Sons

- [10] Timeline of French Physicians, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. #27 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #19 | Whewell's Ghost