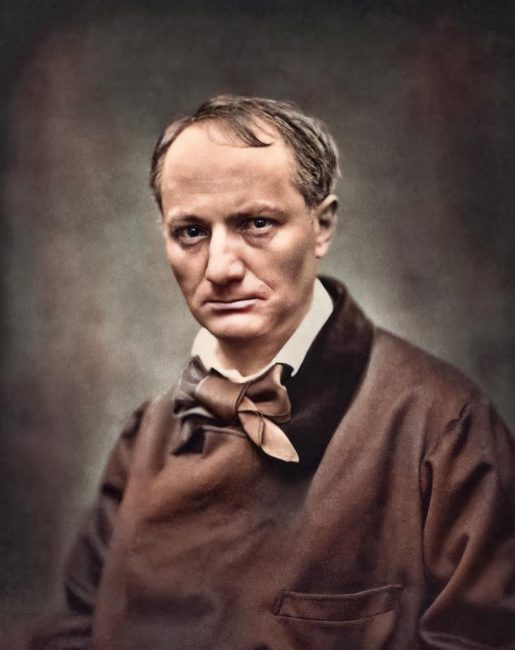

Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867)

On April 9, 1821, French poet Charles Baudelaire was born. He produced notable work as an essayist, art critic, and pioneering translator of Edgar Allan Poe. Baudelaire is most famous work, Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), expresses the changing nature of beauty in modern, industrializing Paris during the 19th century. Baudelaire is considered one of the major innovators in French literature. His themes of sex, death, lesbianism, metamorphosis, depression, urban corruption, lost innocence and alcohol not only gained him loyal followers, but has ever since become a subject of controversy.

“Everything that gives pleasure has its reason. To scorn the mobs of those who go astray is not the means to bring them around.”

– Charles Baudelaire, “Quelques mots d’introduction,” Salon de 1845 (May 1845)

Early Years

Charles Baudelaire was born in Paris, France, to his father François Baudelaire, a senior civil servant and amateur artist, and his wife, Caroline. Baudelaire’s father, who was thirty years older than his mother, died when the poet was six. In 1827, Caroline married Lieutenant Colonel Jacques Aupick, who later became a prominent ambassador. In 1833, the family moved to Lyons where Baudelaire studied law at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand. Dissatisfied with his choice of profession, he began to drink daily, hire prostitutes and run up considerable debts. Upon obtaining his degree in 1839, Baudelaire chose not to pursue law any further, but turned to a career in literature. Thus, he spent the next two years in Paris’ Latin Quarter accumulating debt. It is also believed that he contracted syphilis around this time.

“All beauties, like all possible phenomena, have something of the eternal and something of the ephemeral — of the absolute and the particular.”

– Charles Baudelaire, “De l’héroïsme de la vie moderne,” Salon de 1846, XVIII (1846)

The Poet-in-Waiting

His mother and stepfather stepped in a couple years later and offered him a trip to India with the hope that the young “rebel” would adjudicate his ways. In 1841, Charles Baudelaire set sail on his ‘imposed’ adventure only to return within ten months. Upon his return to Paris, Charles Baudelaire also received his inheritance, a handsome 75,000 francs, which he was demanding after achieving adulthood. The “un-reformed” poet-in-waiting thus embarked on his luxurious bohemian lifestyle, which included a penchant for fashion, experimenting with hashish and opium, and a ‘commitment’ to spending his days frequenting artists and cafes. Having gone through almost half of his inheritance in only 18 months, for which he received active support from his new lover, the actress Jeanne Duval, whose exotic beauty he wrote about, his parents managed a court order in 1844 to control his funds dispensing it in small increments over the rest of his life.

An Unprofitable Author

His writing, which he now tried to pursue more systematically and professionally, remained unprofitable. Sporadically he succeeded in placing poems in magazines. In 1846 and 1847 he published two novels, also in magazines, as his only somewhat longer narrative texts: the pretty love story Le jeune enchanteur (“The Young Enchanter“), supposedly from antiquity, cleverly divided by alleged gaps in the text, and the artist’s novella La Fanfarlo (first rejected and then printed more by chance), which seems to reflect Baudelaire’s metamorphosis from a poem-making dandy to an almost bourgeois author and quasi-husband, wittily encoded and full of sparkling self-irony. The novella deals with Baudelaire’s love affair with his muse Jeanne Duval. He found a certain recognition only with the reports about art exhibitions (salons), which he wrote from 1845 with increasing competence. Since he had become accustomed to the consumption of hashish, opium and alcohol and also endured Jeanne Duval, he was constantly in financial difficulties, which in turn increased his tendency to depression.

Jeanne Duval, painted by Édouard Manet in 1862 (Budapest Museum of Fine Arts)

Discovering a Twin Soul

Charles Baudelaire’s disdain for the growing bourgeoisie escalated and he became politically involved and participated in the infamous 1848 revolution, which culminated in the coronation of Napoleon III, much to Baudelaire’s disillusionment. It was also at this time that he discovered Edgar Allan Poe and thought of him as his “twin soul” and he would publish translations of his work in 1854 and 1855.[5,6]

The Poet is a kinsman in the clouds

Who scoffs at archers, loves a stormy day;

But on the ground, among the hooting crowds,

He cannot walk, his wings are in the way.

– Les Fleurs du Mal, “L’Albatros” [The Albatross], 1857, (translated by James McGowan, Oxford University Press, 1993)

In 1856, he published a volume of stories by Poe and introduced it to French readers in a lengthy preface that is considered an important contemporary source on the author. In 1858 he completed his Poe translations with the Aventures d’Arthur Gordon Pym.

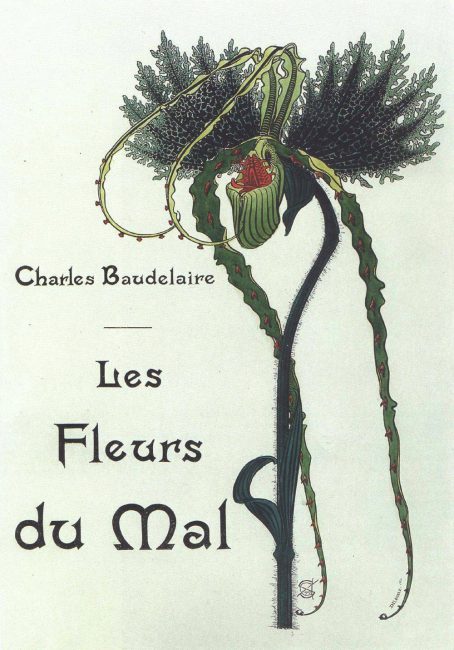

The Flowers of Evil

Illustration of Les Fleurs du Mal by Carlos Schwabe, 1900

His most famous work, Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), a collection of 100 poems, appeared on June 1857, and in July the Ministry of the Interior banned the volume, accusing the author of “outrage to public decency”. All involved – author, publisher, and printer – were prosecuted and found guilty of obscenity and blasphemy. “You – hypocrite Reader – my double – my brother!“. In the prefatory poem of The Flowers of Evil Baudelaire makes his reader as guilty of sins and lies as the poet:

“If poison, arson, sex, narcotics, knives

have not yet ruined us and stitched their quick,

loud patterns on the canvas of our lives,

it is because our souls are still too sick.“

The basic moods of these formally and linguistically sophisticated, mostly rather short poems are (as is often the case with the Romantics) disillusionment, pessimism, melancholy; evoked reality (unlike the Romantics) appears to be predominantly ugly and morbid, man as torn between the powers of light and good (“l’idéal“) and those of darkness and evil, even Satan (“le spleen“). One of Baudelaire’s most significant innovations in the Fleurs is the integration, albeit sparing, of the world of the metropolis into poetry – a world presented as rather repulsive and gloomy overall, which, however, corresponded perfectly to the reality in the overpopulated, explosively growing and dirty Paris of the time.

Later years

In 1860 he also fell in love with the enthusiasm for composer Richard Wagner, which was rampant in Paris, and he published a longer Étude sur Richard Wagner et Tannhäuser. The remaining years of Baudelaire’s life were darkened by despair and financial difficulties. He moved to Brussels in 1863 on a lecturing tour but he suffered a series of strokes that left him partially paralyzed and with a severe speech impediment. He returned to Paris in 1864 from extended stay in Brussels and stayed in a sanatorium. He died in Paris of aphasiac and hemiplagiac on August 31, 1867, in his mother’s arms. Baudelaire is regarded as a father of Symbolism, as a founder of prose poetry and as the inspiration for numerous contemporary poets and successors into the twentieth century. His works have been set to music by several composers including Chausson and Debussy.

For his direct contemporaries, i.e. not too many readers who knew his name, Baudelaire was above all a competent writer of reports on art exhibitions, a good literary critic, a diligent translator of poetry, and a Wagner enthusiast and promoter. He was regarded as an epoch-making model for the following generation of poets, the Symbolists (e.g. Verlaine, Mallarmé or Rimbaud). Baudelaire himself did not experience this recognition.

Resonances of Baudelaire in Debussy’s Piano Music – Roy Howat, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Charles Baudelaire at biographies.com

- [2] Baudelaire at poets.org

- [3] Charles Baudelaire at the European Graduate School

- [4] Charles Baudelaire’s Fleur du mal

- [5] Quoth the Raven ‘Nevermore’, SciHi Blog

- [6] The mysterious Death of Edgar Allan Poe, SciHi Blog

- [7] Les Fleur du mal at Wikisource

- [8] Works by or about Charles Baudelaire at Internet Archive

- [9] Poems by Charles Baudelaire—Selected works at Poetry Archive

- [10] Charles Baudelaire at Wikidata

- [11] Resonances of Baudelaire in Debussy’s Piano Music – Roy Howat, Gresham College @ youtube

- [12] Hyslop, Lois Boe (1980). Baudelaire, Man of His Time. Yale University Press.

- [13] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Baudelaire, Charles Pierre“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 536–537.

- [14] Richardson, Joanna (1994). Baudelaire. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- [15] Timeline for Charles Baudelaire, via Wikidata