John Ray. Line engraving after Mary Beale

Image Source: Wellcome Library, London

On November 29, 1627, English naturalist John Ray was born. He published important works on botany, zoology, and natural theology. His classification of plants in his Historia Plantarum, was an important step towards modern taxonomy. He advanced scientific empiricism against the deductive rationalism of the scholastics and was the first to give a biological definition of the term species.

“I cannot but look upon the strange Instinct of this noisome and troublesome Creature a Louse, of searching out foul and nasty Clothes to harbor and breed in, as an Effect of divine Providence, design’d to deter Men and Women from Sluttishness and Sordidness.”

– John Ray, The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation (1691). p. 309

John Ray – Early Years

John Ray was born in the village of Black Notley in Essex. He is said to have been born in the smithy, his father having been the village blacksmith. During his childhood, John Ray enjoyed watching his father working in the forge and taking long walks with his mother in the nature, collecting numerous herbs. He came to love the nature and especially plants and their medical uses. Ray was educated at the Braintree Grammar School, Catherine Hall at Cambridge University, and Trinity College. The student was especially talented in the fields of mathematics, languages and natural sciences. During a longer period of illness, Ray began to explore the countryside around Cambridgeshire where he slowly recovered and he later wrote about this period:

“there was leisure to contemplate by the way what lay constantly before the eyes and were so often trodden thoughtlessly underfoot… the shape, colour and structure of particular plants fascinated and absorbed me: interest in botany became a passion.”

Travels through Europe

By that time, Ray already made the decision to extent his studies and intended to not only find, but also name and classify all living things and in order to do so, he began a long journey together with his friends across Britain and Europe. In the spring of 1663 Ray started together with Francis Willughby and two other students (Philip Skippon and Nathaniel Bacon) on a tour through Europe, from which he returned in March 1666, parting from Willughby at Montpellier, whence the latter continued his journey into Spain. He had previously in three different journeys (1658, 1661, 1662) travelled through the greater part of Great Britain, and selections from his private notes of these journeys were edited by George Scott in 1760, under the title of Mr Ray’s Itineraries. Ray himself published an account of his foreign travel in 1673, entitled Observations topographical, moral, and physiological, made on a Journey through part of the Low Countries, Germany, Italy, and France. From this tour Ray and Willughby returned laden with collections, on which they meant to base complete systematic descriptions of the animal and vegetable kingdoms.

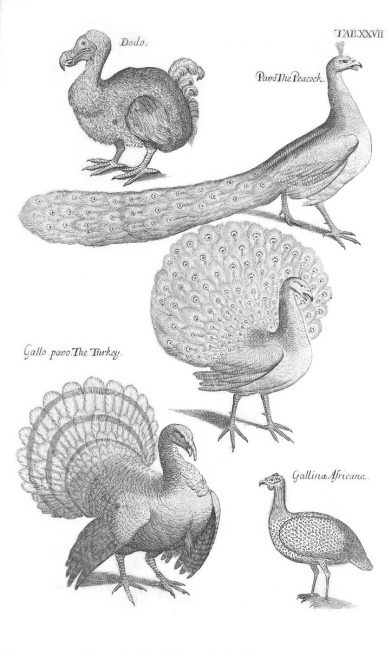

Woodcuts of Dodo, Peacock, Turkey, Guineafowl from Willughby’s and Ray’s Ornithology 1678

The Catalogue of English Plants

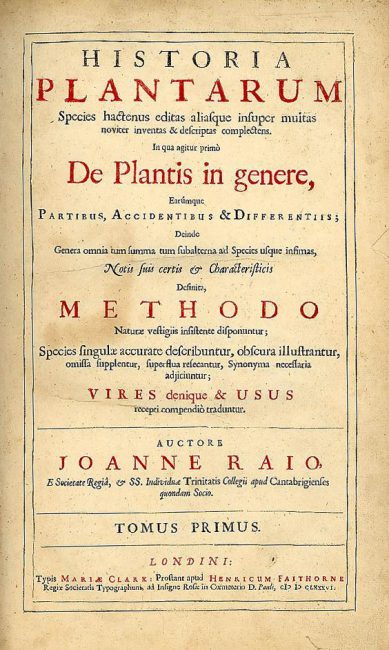

John Ray published the Catalogue of English Plants in 1670, which included a scientific record of English plants as well as an index with details of their possibilities in medical uses. Another one of his famous works was A Collection of English Proverbs, but, the Historia Plantarum was probably his most famous and most influential. It was published in three volumes between 1686 and 1704. [3] In the masterpiece, Ray intended to summarize all his knowledge of the plant world and up to this day, his descriptions are seen as “masterpieces of brevity and completeness“. The preface of the book contains a survey of all knowledge of the kingdom of plants back then and also summarized the works by contemporary researchers. In the first two volumes, about 7000 species of European plants are described and classified. The book is up to this day considered as a remarkable step in the development of science. [1]

Title page of Historia Plantarum, John Ray, 1686

Ray was the first person to produce a biological definition of species, in his 1686 History of Plants:

“… no surer criterion for determining species has occurred to me than the distinguishing features that perpetuate themselves in propagation from seed. Thus, no matter what variations occur in the individuals or the species, if they spring from the seed of one and the same plant, they are accidental variations and not such as to distinguish a species… Animals likewise that differ specifically preserve their distinct species permanently; one species never springs from the seed of another nor vice versa”

Later Years

To one of John Ray’s last impressive works belongs the theological book The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation, published in 1691. Later on, he devoted his life to the systematic study of insects, while the majority of the specimens were caught by his wife and daughters. Unfortunately, his Historia Insectorum remained unfinished. John Ray passed away on January 17, 1705. [2] Ray’s works were directly influential on the development of taxonomy by Carl Linnaeus.[4] Ray’s biographer, Charles Raven, commented that “Ray sweeps away the litter of mythology and fable… and always insists upon accuracy of observation and description and the testing of every new discovery“.

Sir Roderick Floud: The Hidden Face of British Gardening, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] John Ray, Naturalist: His Life and Works by Charles Earle Raven

- [2] John Ray at Berkeley University

- [3] John Ray at Braintree Museum

- [4] Carl Linnaeus – ‘Princeps Botanicorum’, the Prince of Botany, SciHi Blog

- [5] Memoir of John Ray by James Duncan

- [6] De Variis Plantarum Methodis Dissertatio Brevis at Europeana

- [7] Works by or about John Ray at Wikisource

- [8] John Ray at Wikidata

- [9] Sir Roderick Floud: The Hidden Face of British Gardening, Gresham College @ youtube

- [10] Mullens, W.H. (1909). “Some early British Ornithologists and their works. VII. John Ray (1627-1705) and Francis Willughby (1635-1672)”. British Birds. 2 (9): 290–300.

- [11] Gunther, R.W.T., ed. (1928). Further Correspondence of John Ray. Ray Society.

- [12] John Ray’s works at the Biodiversity Heritage Library

- [13] Timeline of Pre-Linnaean Biologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #21 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #16 | Whewell's Ghost