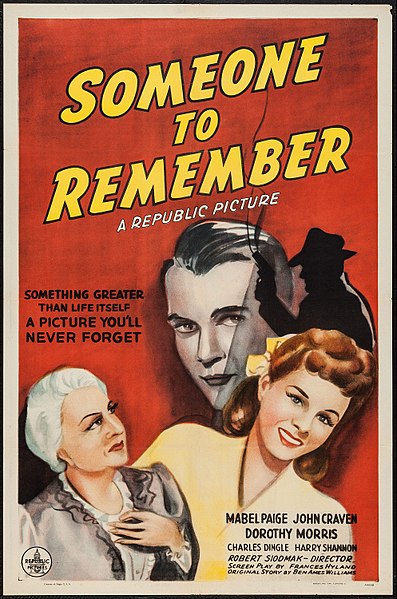

Robert Siodmak, Poster for the 1943 film “Someone to Remember”

On August 8, 1900, German film director, writer, and producer Robert Siodmak was born. In 1929 he shot the film Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday), one of the most important representatives of New Objectivity. Like many filmmakers of his time, he fled from Germany before the National Socialist dictatorship. He is best remembered as a thriller specialist and for a series of stylish, unpretentious Hollywood films noirs he made in the 1940s, most notably The Killers (1946).

Early Years

Robert Siodmak came from a Jewish family. His parents were the merchant Ignatz Siodmak and his wife Rosa Philippine, née Blum. Ignatz Siodmak originally came from Silesia, emigrated to America and then settled in Germany in 1899 as an American citizen, where he married. Siodmak attended high school in Dresden and took acting lessons with Erich Ponto. In 1918 he joined a travelling theatre, in 1921 he worked as an accountant at the banks Mattersdorf and Schermer in Dresden, in 1924 he founded the “Verlag Robert Siodmak” and briefly published the magazine Das Magazin. At the Nero film in Berlin, directed by his uncle Heinrich Nebenzahl, he established himself as editor and assistant director for films by Harry Piel and Kurt Bernhardt. Finally, Siodmak could persuade Nebenzahl to provide him with the seed money for his debut film Menschen am Sonntag.

Menschen am Sonntag

For the first time Robert Siodmak directed Menschen am Sonntag (shot 1929, premiered in 1930) together with Edgar G. Ulmer. Due to the success of this semi-documentary film, which is exclusively made up of amateurs, he received a contract from Universum Film (UFA) for which he directed film dramas, detective films and film comedies. In 1933 The Burning Secret, Siodmak’s screen version of Stefan Zweig‘s novel Burning Secret, was published. The film was banned by Joseph Goebbels‘ Reich Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, which had been established shortly before and suspected allusions to the Reichstag fire of 27 February 1933.

Emigration

After the National Socialists seized power, Siodmak left Germany and went to France. In Paris he worked for his cousin Seymour Nebenzahl’s Néro films, who like Siodmak had had to emigrate. The greatest public success of this creative period was the film White Slave Trader (Pièges) with Maurice Chevalier, Marie Déa and Erich von Stroheim in 1939.

Bringing the Expressionist Look to Hollywood

Siodmak emigrated to the USA at the beginning of the Second World War. He first worked for Paramount Pictures, 20th Century Fox and Republic Pictures. His application to Mark Hellinger, then producer at Warner Brothers, was unsuccessful, although Hellinger later hired him for Avengers of the Underworld. In 1943 he shot his first film with Dracula’s son for Universal Studios, where he remained under contract until 1950. In retrospect, Siodmak was derogatory about his American films made before Witness Wanted (1944), which he regarded as pure bread works. His first all-out noir was Phantom Lady (1944), for staff producer Joan Harrison, Universal’s first female executive and Alfred Hitchcock‘s former secretary and script assistant.[2] A classic, however flawed, it showcased Siodmak’s skill with camera and editing to dazzling effect. Siodmak’s use of black-and-white cinematography and urban landscapes, together with his light-and-shadow designs, followed the basic structure of classic noir films. In fact, he had as number of collaborations with cinematographers, such as Nicholas Musuraca, Elwood Bredell, and Franz Planer, in which he achieved the Expressionist look he had cultivated in his early years at UFA.

The Killers

During Siodmak’s tenure, Universal made the most of the noir style in The Suspect, The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry and The Dark Mirror, but the capstone was The Killers in 1946, Burt Lancaster‘s film debut and Ava Gardner‘s first dramatic, featured role. A critical and financial success, it earned Siodmak his only Oscar nomination for direction in Hollywood. Siodmak immersed himself in the creative process and genuinely loved working with actors; in fact, he was considered an actor’s director, discovering Burt Lancaster, Ernest Borgnine, Tony Curtis, Debra Paget, Maria Schell, Mario Adorf, and skillfully directing actresses, such as Ava Gardner, Olivia de Havilland, Dorothy McGuire, Yvonne de Carlo, Barbara Stanwyck, Geraldine Fitzgerald, and Ella Raines.

Postwar Career

In the mid-1950s Siodmak settled in Ascona on the Swiss shore of Lake Maggiore and again directed in Germany. Once again he was active in such diverse fields as criminal film, film drama, western and historical film. “If I, like Hitchcock, had only made crime films my whole life, my name would certainly be equally well-known. But that bored me and I tried it in different areas.” For Die Ratten (The Rats, 1955), his film adaptation of Gerhart Hauptmann‘s play of the same name, he was awarded the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival. Staged by him in 1957 Nachts, wenn der Teufel kam (The Devil came at Night), he received numerous national and international awards, including an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. The film deals with the case of the alleged serial killer Bruno Lüdke against the historical background of National Socialism.[9] In his autobiography, Siodmak noted that he was only proud of these two films he made after his return from the USA.

Later Years

In 1964 and 1965 Siodmak directed three of Artur Brauner‘s Karl May [3] film adaptations: Der Schut, Der Schatz der Azteken and Die Pyramide des Sonnengottes. In Spain, Siodmak shot the Western A Day of Fighting for US producer Philip Yordan. In 1968 and 1969, the two-part monumental film Kampf um Rom (The Battle of Rome), was published after Felix Dahn‘s historical novel, the last film directed by Siodmak. Nevertheless, he showed great interest in international cinematic events until the very end, was impressed by the French Nouvelle Vague, by Italian cinema and by Francis Ford Coppola‘s The Godfather.

Controversial Appreciation

However, the appreciation of Robert Siodmak’s cinematographic work was often subject of dispute. Critic Andrew Sarris reckoned that his American films were more Germanic than his German ones, while others feud over whether he was an auteur who helped define film noir or a studio hack whose work was decidedly mediocre when not abetted by quality craftsmen. Moreover, while Siodmak was feted in some quarters as the new Fritz Lang or Alfred Hitchcock, he was appreciated in others as a master of kitsch.[5,6]

On March 10, 1973, Robert Siodmak died of a heart attack at the age of 72.

Thomas Elsaesser at The Dr. Saul and Dorothy Kit Film Noir Festival (2018), [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Robert Siodmak on IMDb

- [2] The Art of Suspense – Alfred Hitchcock’s Cinema, SciHi blog

- [3] Karl May’s Fantastic Adventures, SciHi blog

- [4] “Robert Siodmak, film director, 72“, obituary at The New York Times, March 12, 1973.

- [5] David Parkinson, How to get into… film noir master Robert Siodmak, at BFI (British Film Institute), November 2016.

- [6] M – A City looks for a Murderer, SciHi Blog

- [7] Robert Siodmak at Wikidata

- [8] Thomas Elsaesser at The Dr. Saul and Dorothy Kit Film Noir Festival (2018), The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of: Paris 1946 and American Film Noir, CUSchooloftheArts @ youtube

- [9] Glaser, Emeli (3 September 2021). “The invented serial killer”. Die Tageszeitung.

- [10] Wolfgang Jacobsen: Siodmak, Robert. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-11205-0, S. 475 f.

- [11] Timeline for Robert Siodmak, via Wikidata