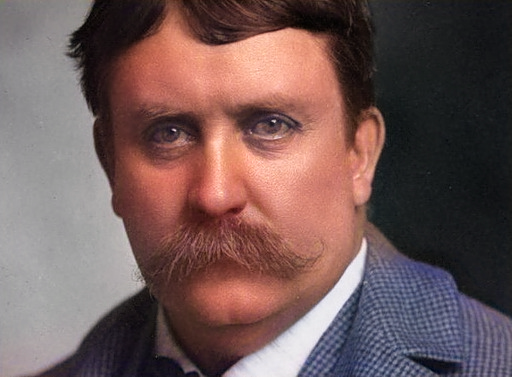

Daniel Burnham (1846-1912)

On September 4, 1846, American architect and urban designer Daniel Burnham was born. Burnham took a leading role in the creation of master plans for the development of a number of cities, including Chicago, Manila and downtown Washington, D.C. He also designed several famous buildings, including the Flatiron Building of triangular shape in New York City, Union Station in Washington D.C., the Continental Trust Company Building tower skyscraper in Baltimore, and a number of notable skyscrapers in Chicago.

“Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency. Remember that our sons and our grandsons are going to do things that would stagger us.” — Daniel Burnham (1907)[2]

Youth and the Swedenborgian Chruch

Daniel Hudson Burnham was born in Henderson, New York and raised in Chicago, Illinois, as the sixth of seven children and the youngest son. His parents brought him up under the teachings of the Swedenborgian called The New Church, a maverick Christian religious sect named for Emanuel Swedenborg, a Swedish scientist and mystic who disagreed with church hierarchy and stressed being of service to others. Burnham and his family moved to Chicago in 1855. There he attended Snow’s Swedenborgian Academy and later Central High School. In 1863, after he had graduated, his parents sent him to the newly incorporated New-Church Theological School in Waltham, Mass., for further study. He prepared for college with a Swedenborgian tutor, the Reverend Tilly Brown Hayward. Through Hayward, Burnham met the architect and writer W.P.P. Longfellow, who encouraged Burnham’s interest in architecture. When it came time to take his college entrance exams at Harvard and Yale, he failed both because he was “not able to write a word,” as he later recalled. Years later both universities would award him honorary degrees.[1]

From Draftsman to Architect

In his early adulthood, Burnham worked as retail clerk, mined for gold in Nevada, and ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the Illinois State Senate. Still in his early twenties, Burnham was accepted as an apprentice by a leading Chicago architect and civil engineer, William Le Baron Jenney.[2] In 1872 Burnham, age twenty-six, moved to the firm of Carter, Drake, and Wight, where he worked as a draftsman. A year later he went into partnership with a fellow draftsman at the firm, John Wellborn Root, what turned out to be a profitable partnership. Root was creative and versatile; Burnham, practical and businesslike, was a superb administrator. As best friends and professional colleagues, they worked closely together. They prospered after the Great Chicago Fire, which decimated downtown Chicago. Between 1873 and 1891 the firm designed 165 private residences and 75 buildings of various types.[2]

Transforming Chicago’s Citiscape

In 1891 Burnham and Root adapted modern techniques to meet the demand for more centralized office space in Chicago. Three of their buildings have been designated landmarks. The Rookery (1886) and the Reliance Building (1890) both used a skeleton frame construction. The sixteen-story Monadnock building (1891) was the last and tallest American masonry skyscraper.[2] Measuring 21 stories and 302 feet, the temple held claims as the tallest building of its time, but was torn down in 1939. Under the design influence of Root, the firm had produced modern buildings as part of the Chicago School. Burnham and Root had accepted responsibility to oversee design and construction of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago’s then-desolate Jackson Park on the south lakefront. The largest world’s fair to that date (1893), it celebrated the 400-year anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ famous voyage.

The Rookery Building in Chicago, (1886)

The White City

Following Root’s premature death from pneumonia in 1891, the firm became known as D.H. Burnham & Company. A team of distinguished American architects and landscape architects, including Burnham, Frederick Law Olmsted, Charles McKim and Louis Sullivan,[5] radically changed Root’s modern and colorful style to a Classical Revival style. Under Burnham’s direction, the construction of the World’s Columbian Exposition overcame huge financial and logistical hurdles, including a worldwide financial panic and an extremely tight timeframe, to open on time. Nicknamed the “White City,” the fair’s grand Neoclassical buildings were planned as a cohesive whole in a landscaped setting; they made a lasting impression on millions of visitors.[1] Considered the first example of a comprehensive planning document in the nation, the fairground was complete with grand boulevards, classical building facades, and lush gardens. Often called the “White City”, it popularized neoclassical architecture in a monumental and rational Beaux-Arts plan. The remaining population of architects in the U.S. were soon asked by clients to incorporate similar elements into their designs.

Court of Honor and Grand Basin — World’s Columbian Exposition

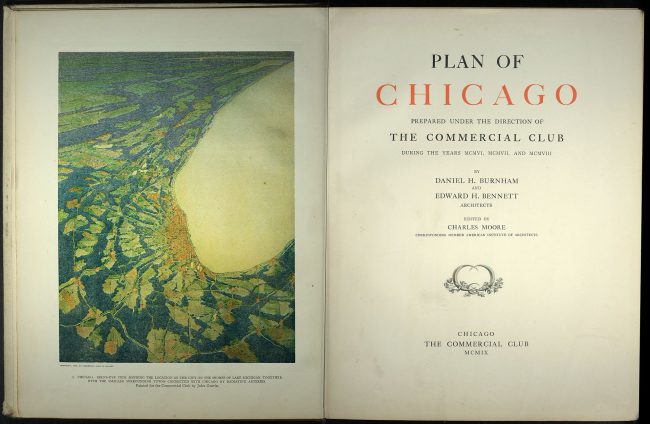

The Plan of Chicago

Initiated in 1906 and published in 1909, Burnham and his co-author Edward H. Bennett prepared “The Plan of Chicago”, which laid out plans for the future of the city. It was the first comprehensive plan for the controlled growth of an American city, and an outgrowth of the City Beautiful movement. The plan included ambitious proposals for the lakefront and river and declared that every citizen should be within walking distance of a park. City planning projects did not stop at Chicago though. Burnham had previously contributed to plans for cities such as Cleveland (the 1903 Group Plan), San Francisco (1905), and Manila (1905) and Baguio in the Philippines, details of which appear in “The Chicago Plan” publication of 1909. In Washington, D.C., Burnham did much to shape the 1901 McMillan Plan, which led to the completion of the overall design of the National Mall.

Title page of Daniel Burnham’s Plan of Chicago, Daniel Hudson Burnham; Edward H Bennett; Charles Moore; Commercial Club of Chicago.

Later Years

Much of Burnham’s work was based on the classical style of Greece and Rome. In addition to his work as an urban planner, by the time of his death in 1912 Burnham was responsible for the design of several important buildings, including the Flatiron Building, New York (1901); Union Station, Washington, D.C. (1909); and Filene’s Store, Boston (1912). Each of these buildings had a lasting influence on the twentieth century cityscape, and through them, Daniel Burnham’s vision endures.

Daniel Burnham died on June 1, 1912, of food poisoning while on a trip abroad, aged 65.

The City as Image, Daniel Burnham’s Plan for Chicago, [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Daniel Burnham, American architect, at Britannica Online

- [2] Charles Moore (1921): Daniel H. Burnham, Architect, Planner of Cities. Volume 2. Chapter XXV “Closing in 1911-1912;” p. 147.

- [3] “Burnham, Daniel Hudson.” Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History. . Encyclopedia.com. 3 Sep. 2017

- [4] Daniel Burnham at Wikidata

- [5] Louis Henry Sullivan – the ‘Father’ of the Skyscaper, SciHi Blog

- [6] The City as Image, Daniel Burnham’s Plan for Chicago, Donna Guerrero @ youtube

- [7] Burnham, Daniel H. and Bennett, Edward H. (1910) Plan of Chicago, Chicago: The Commercial Club

- [8] Jameson, D. “Daniel Hudson Burnham”. Artists Represented.

- [9] Randall, Frank Alfred; John D. Randall (1999). History of the Development of Building Construction in Chicago. Urbana and Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

- [10] Hines, Thomas S. (June 15, 1979). Burnham of Chicago: Architect and Planner. University of Chicago Press.

- [11] Timeline for Daniel Burnham, via Wikidata