Roger Wolcott Sperry (1913 – 1994)

On August 20, 1913, American neuropsychologist, neurobiologist and Nobel laureate Roger Wolcott Sperry was born. Sperry is known for his work with split-brain research. in particular for his study of functional specialization in the cerebral hemispheres. He was responsible for overturning the widespread belief that the left brain is dominant by showing that several cognitive abilities were localized in the right brain.

“The objective psychologist, hoping to get at the physiological side of behavior, is apt to plunge immediately into neurology trying to correlate brain activity with modes of experience … The result in many cases only accentuates the gap between the total experience as studied by the psychologist and neural activity as analyzed by the neurologist.”

– Roger Wolcott Sperry, “Action Current Study in Movement Coordination” in Journal of General Psychology (1939)

Roger Wolcott Sperry – Background

Roger Wolcott Sperry was born in Hartford, Connecticut, U.S., in 1913 and grew up in West Hartford, where he attended West Hartford High School. With the help of a scholarship he studied at Oberlin College, which he graduated with a BA in English in 1935. Even though he majored in English, Sperry took an Intro to Psychology class taught by a Professor named R. H. Stetson who had worked with William James, the father of American Psychology. Sperry’s enthusiasm for the brain was sparked and even more through the time he spent with Stetson. The researcher was handicapped and Roger Sperry helped him get around including taking Stetson to lunch with his colleagues. Sperry listened to Stetson and his colleagues discuss their work and became so curious that he decided to continue his education and with a master’s degree in Psychology. Roger Sperry received his master’s degree in psychology in 1937 followed by his Ph.D. in zoology from the University of Chicago in 1941 supervised by Paul A. Weiss.

Academic Career

Five years later, Sperry was announced assistant professor, and later associate professor, at the University of Chicago. After Sperry was diagnosed with tuberculosis, he was sent to Saranac Lake in the Adironack Mountains in New York, where he began writing his concepts of the mind and brain which was first published in the American Scientist in 1952. Sperry was appointed professor at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech as Hixson Professor of Psychobiology) where he performed his most famous experiments with Joseph Bogen, MD and many students including Michael Gazzaniga.

Nature or Nurture?

Already early in his studies, Roger Sperry became interested in neuronal specificity and brain circuitry and began questioning the existing concepts about these two topics. He asked the simple question Nature or nurture? And Sperry began a series of experiments in an attempt to answer this question. For instance, the scientist replaced the motor nerves from the right hind legs of rats with the motor nerves in the left hind legs of other rats and vice versa. After placing the rats in a cage with an electric grid on the bottom, he administered shocks to a specific section of the grid, for example the grid where the rat’s left back leg was located would receive a shock. Every time the left paw was shocked the rat would lift his right paw and vice versa. Sperry wanted to know how long it would take the rat to realize he was lifting the wrong paw. After repeated tests Sperry found that the rats never learned to lift up the correct paw, leading him to the conclusion that some things are just hardwired and cannot be relearned. In Sperry’s words, “no adaptive functioning of the nervous system took place.”

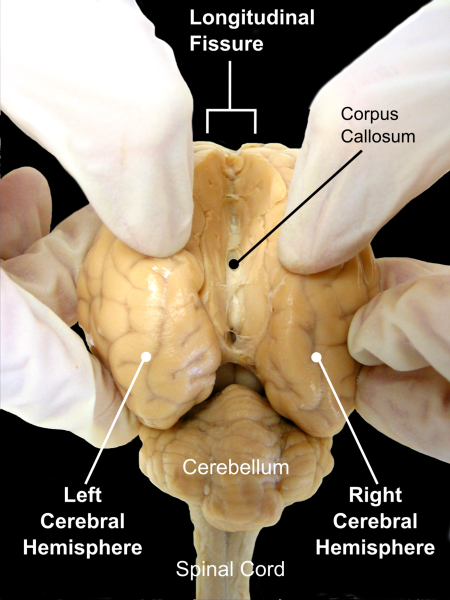

The sheep brain seen from the back. Opening longitudinal fissure, the fissure which separates left and right cerebral hemispheres

Chemoaffinity Hypothesis

Roger Sperry continued his experimental work at Harvard and at the Yerkes Laboratories of Primate Biology in Orange Park, Florida. Sperry’s new work involved salamanders. He sectioned the optic nerves and rotated the eyes 180 degrees to find out whether their vision would be normal after regeneration or would the animal forever view the world as “upside down” and right-left reversed. As a result, the animals reacted as though the world was upside down and reversed from right to left. Furthermore, no amount of training could change the response. These studies, which provided strong evidence for nerve guidance by “intricate chemical codes under genetic control” (1963) culminated in Sperry’s chemoaffinity hypothesis (1951).[9]

Split-Brain Research

Another testing period concerning “split-brain” research involved cats. The animals’ eye nerves were connected to the ‘wrong’ hemisphere and in addition the corpus callosum connecting the two halves of the brain was cut. The cats were then taught to distinguish a triangle from a square with the right (then left) eye covered. The cats had no idea what they had just learned with the right eye and because of this could be taught to distinguish a square from a triangle. Depending on which eye was covered, the cats would either distinguish a square from a triangle or a triangle from a square, demonstrating that the left and right hemispheres learned and remembered two different events. This led Sperry to believe that the left and right hemispheres function separately when not connected by the corpus callosum. Due to these findings, it was believed that cutting the corpus callosum is a very effective treatment for patients who suffer from epilepsy.[11]

Roger Sperry came to the conclusion that each hemisphere is “indeed a conscious system in its own right, perceiving, thinking, remembering, reasoning, willing, and emoting, all at a characteristically human level, and … both the left and the right hemisphere may be conscious simultaneously in different, even in mutually conflicting, mental experiences that run along in parallel“.

Nobel Prize and Later Years

The research of Roger Wolcott Sperry contributed greatly to understanding the lateralization of brain function. Sperry was granted numerous awards over his lifetime, including the California Scientist of the Year Award in 1972, the National Medal of Science in 1989, the Wolf Prize in Medicine in 1979, and the Albert Lasker Medical Research Award in 1979, and the Nobel Prize for Medicine/Physiology in 1981 that he shared with David H. Hubel and Torsten N. Wiesel. Sperry won this award for his work with “split-brain” patients.

Roger Wolcott Sperry died on April 17, 1994, at age 80.

Nancy Kanwisher – Human Cognitive Neuroscience, [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Roger Wolcott Sperry at the Nobel Prize Foundation

- [2] Roger Wolcott Sperry Webpage

- [3] Roger Sperry at Wikidata

- [4] Oliver Sacks and his serious and at the same time exciting literary Case Studies, SciHi Blog

- [5] Phineas Gage’s Accident and the Science of the Mind and the Brain, SciHi Blog

- [6] Nancy Kanwisher – Human Cognitive Neuroscience, MIT RES.9-003 Brains, Minds and Machines Summer Course, Summer 2015, MIT OpenCourseWare @ youtube

- [7] Miller, J. G. (1994). “Roger Wolcott Sperry. Born August 20, 1913—died April 17, 1994”. Behavioral Science. 39 (4): 265–267.

- [8] Voneida, T. J. (1997). “Roger Wolcott Sperry. 20 August 1913–17 April 1994: Elected For.Mem.R.S. 1976”. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 43: 463–470.

- [9] Sperry, R. W. (1963). “Chemoaffinity in the Orderly Growth of Nerve Fiber Patterns and Connections”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 50 (4): 703–710.

- [10] Sperry, R. W. (1951). “Regulative factors in the orderly growth of neural circuits”. Growth (Suppl 10): 63–87

- [11] Sperry, R. W. (1961). “Cerebral Organization and Behavior: The split brain behaves in many respects like two separate brains, providing new research possibilities”. Science. 133 (3466): 1749–1757.

- [12] Puente, Antonio E. (1995). “Roger Wolcott Sperry (1913–1994)”. American Psychologist. 50 (11): 940–941.

- [13] Timeline for Roger Wolcott Sperry, via Wikidata