Thomas Pennant (1726-1798)

On June 14, 1726, Welsh naturalist, traveller, writer and antiquarian Thomas Pennant was born. As a naturalist he had a great curiosity, observing the geography, geology, plants, animals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish around him and recording what he saw and heard about. He wrote acclaimed books including British Zoology, the History of Quadrupeds, Arctic Zoology and Indian Zoology although he never travelled further afield than continental Europe.

Thomans Pennant – Early Years

Thomas Pennant was born into a family of Welsh gentry in Downing Hall, Whitford, Flintshire, Wales. He received his early education at Wrexham Grammar School, before moving to Thomas Croft’s school in Fulham in 1740. According to his own account, it was Francis Willughby‘s Ornithology which raised his interest for natural history. In 1744 he entered Queen’s College, Oxford, later moving to Oriel College. Like many students from a wealthy background, he left Oxford without taking a degree, although in 1771 his work as a zoologist was recognised with an honorary degree. A visit to Cornwall in 1746–1747 awakened an interest in minerals and fossils which formed his main scientific study during the 1750s. In 1750, his account of an earthquake at Downing was inserted in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, where there also appeared in 1756 a paper on several coralloid bodies he had collected at Coalbrookdale, Shropshire. More practically, Pennant used his geological knowledge to open a lead mine, which helped to finance improvements at Downing after he had inherited the estate in 1763.

A Patron and Collector

In 1754, he was elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries but by 1760 after being married he resigned his fellowship. When his financial circumstances later improved, he became a patron and collector. He amassed a considerable collection of works of art, many of which had been commissioned and which were selected for their scientific interest rather than their connoisseur value. His portrait by Thomas Gainsborough shows him as a country gentleman.

Impressing Carl Linnaeus

Pennant’s first publications were scientific papers on the earthquake he had experienced, other geological subjects and palaeontology. One of these so impressed Carl Linnaeus, that in 1757,[8] he put Pennant’s name forward and he was duly elected a member of the Royal Swedish Society of Sciences, and continued to correspond with him further on throughout his life.

The British Zoology

Observing that naturalists in other European countries were producing volumes describing the animals found in their territories, Pennant started, in 1761, a similar work about Britain, to be called British Zoology. This was a comprehensive book with 132 folio plates in colour, published in 1766 and 1767. In February 1765, he set out on a journey to the continent of Europe, he met other naturalists and scientists including the Comte de Buffon and also Voltaire.[4,5] Pennant later complained that the Comte used several of his communications on animals in his Histoire Naturelle without properly attributing them to him.

The King Penguin

In 1767 Pennant was elected a fellow of the Royal Society. About this time he met the much-travelled Sir Joseph Banks and visited him at his home in Lincolnshire. Banks presented him with the skin of a new species of penguin recently brought back from the Falkland Islands. Pennant wrote an account of this bird, the king penguin, and all the other known species of penguin which was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

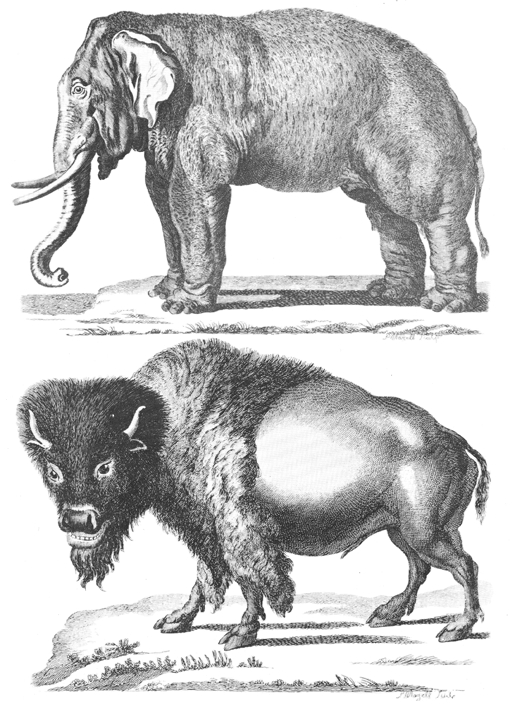

Elephant and bison, from Thomas Pennant’s History of Quadrupeds (1793)

Travel to Scotland

In June 1769 Pennant decided on a journey to Scotland, a relatively unexplored country and not previously visited by a naturalist and kept a journal and made sketches as he travelled. He was unimpressed by the climate but was interested in all he saw and made enquiries about the local economy. He described in detail the scenery around Loch Ness. On his return home, Pennant wrote an account of his tour in Scotland which met with some acclaim and which may have been responsible for an increase in the number of English people visiting the country.

A Synopsis of Quadrupeds

In 1771 Pennant’s Synopsis of Quadrupeds was published. This work, as well as his British Zoology’arranged according to the classification of John Ray,[9] long remained classical works, though in point of style and method of presentment they are greatly inferior to the works of Buffon. Cuvier in his memoir of Pennant, written about 1823 for the Biographie Universelle,’says that Buffon profited by Pennant’s History of Quadrupeds, 1781, though in the third edition Pennant himself has drawn on Buffon.[1,5] At the end of 1771, Pennant published A Tour in Scotland in 1769, which proved so popular that he decided to undertake another journey resulting in A Tour in Scotland, and Voyage to the Hebrides 1772 in two volumes (1774, 1776). These works include so much detail of the countryside, its economy, natural history and the customs of the inhabitants that they are still of interest today by way of comparison with the very different state of things now.

Further Travels

Over the next few years, Pennant made various excursions in North Wales (Tour in Wales, 1778) followed by a Journey to Snowdon (1781 and 1783), and these later jointly became the second volume of his Tour. Pennant’s interests ranged widely. In 1781, he had a paper published in the Philosophical Transactions on the origins of the turkey, arguing that it was a North American bird and not an Old World species. Another paper, published at the instigation of Sir Joseph Banks, was on earthquakes, several of which he had experienced in Flintshire. In 1782, Pennant published his Journey from Chester to London.

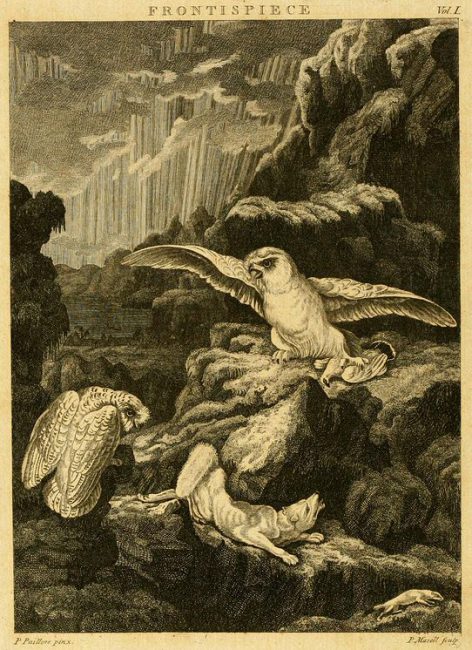

Frontispiece to Arctic Zoology. Painting by Peter Paillou, engraved by Peter Mazell

A Zoology of North America

Originally, he had then intended to write a “Zoology of North America” but since he felt mortified by the loss of British control over America, this was changed to Arctic Zoology, published, with illustrations by Peter Brown, in 1785–1787. The first volume was on quadrupeds and the second on birds. Compilation of the latter was assisted by an expedition Sir Joseph Banks had made to Newfoundland in 1786.The volumes were much acclaimed and Pennant was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society.

A Zoology on Global Scale

Pennant also conceived the idea of publishing a work on zoology at a global scale and set to work on the first two volumes of what was planned to be a fourteen volume series. Each country was to have maps and sketches, colour plates and an account of the country’s production with notes on its natural history. All this was to be gleaned from the writing of others who had seen these places themselves. The first two volumes appeared early in 1798 and covered most of India and Ceylon. Volumes three and four included the parts of India east of the Ganges, Malaysia, Japan and China but before these were published he suffered a gradual decline in health and died in December 1798.

Marc Kirschner (Harvard U) Part 1: The Origin of the Vertebrate Nervous System, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Warwick William Wroth, Thomas Pennant, in Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 44, pp. 321-322.

- [2] Thomas Pennant, Welsh naturalist, at Britannica Online

- [3] Thomas Pennant, at Dictionary of Welsh Biography

- [4] Comte de Buffon and his Histoire Naturelle, SciHi Blog

- [5] Georges Cuvier and the Fossils, SciHi Blog

- [6] Thomas Pennant at Wikidata

- [7] Pennant, Thomas (1798). The literary life of the late Thomas Pennant, Esq. By himself. Benjamin and J. White.

- [8] Carl Linnaeus – ‘Princeps Botanicorum’, the Prince of Botany, SciHi Blog

- [9] Voltaire – Libertarian and Philosopher, SciHi Blog

- [10] John Ray and the Classification of Plants, SciHi Blog

- [11] Works by or about Thomas Pennant at Internet Archive

- [12] Marc Kirschner (Harvard U) Part 1: The Origin of the Vertebrate Nervous System, iBiology @ youtube

- [13] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Pennant, Thomas“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 104.

- [14] Cunningham, G.G. (1834). “Thomas Pennant”. Memoirs of Illustrious Englishmen. Vol. 6. pp. 256–259.

- [15] Timeline of 18th century Zoologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #44 | Whewell's Ghost