Wiener Riesenrad, one of many Viennese landmarks in the film “The Third Man” (1949)

On September 2, 1949, The Third Man, directed by Carol Reed starring Orson Welles and Joseph Cotton, was officially released. Based on a novel by Graham Greene, The Third Man has become an iconic masterpiece that has been voted as the greatest British film of all time by the British Film Institute in 1999. Set in the ruins of post war Vienna it plays with the damaged history of its protagonists, about their friendship as well as of their betrayal. I saw this movie as a kid on tv and I was very much intrigued by the dense and dark black-and-white atmosphere and the thrilling suspense of the movie. Also the famous “zither” score by Anton Karas has become a catchy tune ever since. If you haven’t seen the movie, be warned to continue reading because of spoilers…

“Don’t be so gloomy. After all it’s not that awful. Like the fella says, in Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love – they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock. So long Holly.” — Holly Lime, in The Third Man[1]

Post War Vienna

The film takes place in post-World-War-II Vienna divided into sectors by the victorious allies, American, British, French, and Soviet, and where a shortage of supplies has led to a flourishing black market.[1] The allied powers share the duties of law enforcement in the city. The story focuses on Holly Martins, played by Joseph Cotton, an American who is given a job in Vienna by his friend Harry Lime, played by Orson Welles, but when Holly arrives in Vienna he gets the news that Lime is dead. Martins then meets with Lime’s acquaintances and soon notices that some of their stories are inconsistent, and determines to investigate what he considers a suspicious death. Martins develops a conspiracy theory after learning of a “third man” present at the time of Lime’s death, running into interference from British officer Maj. Calloway, played by Trevor Howard, and falling head-over-heels for Lime’s grief-stricken lover, Anna, played by Alida Valli.

Calloway advises Martins to leave Vienna, but Martins refuses and demands that Lime’s death be investigated. Calloway reluctantly reveals that Lime had been stealing penicillin from military hospitals, and selling it on the black market diluted so much that many patients died. In postwar Vienna, antibiotics were new and scarce outside military hospitals and commanded a very high price. Disillusioned, Martins agrees to leave Vienna.

A Man named Harry Lime

Upon Martins’ last visit to Anna to say good-bye, he finds out that she also knows of Lime’s misdeeds, but that her feelings toward him are unchanged. She tells him she is to be deported. Upon leaving her flat, he notices someone watching from a dark doorway, obviously Lime, who flees, ignoring Martins’s calls. Next day, they meet at Vienna’s Ferris wheel, the Wiener Riesenrad in the Prater amusement park. Lime obliquely threatens Martins’s life but relents when told that the police already know his death and funeral were faked. Lime tries again to escape through the sewers, but the police are there in force. Calloway shoots and wounds Lime. Badly injured, Lime drags himself up a ladder to a street grating exit but cannot lift it. Martins follows Lime, reaches him, but hesitates. Lime looks at him and nods. A shot is heard. Later, Martins attends Lime’s second funeral.

Graham Greene’s Screenplay

Before writing the screenplay, Graham Greene, by then at the height of his power as both a novelist and screenwriter, worked out the atmosphere, characterisation and mood of the story by writing a novella. He wrote it as a source text for the screenplay and never intended it to be read by the general public, although it was later published (after the lim’s release) under the same name as the film. During the shooting of the film, the final scene was the subject of a dispute between Greene, who wanted the happy ending of the novella, and director Carol Reed and producer David O. Selznick, who stubbornly refused to end the film on what they felt was an artificially happy note.

Time out of Joint

In the United Kingdom, The Third Man was the most popular film at the British box office for 1949. In Austria, “local critics were underwhelmed”, and the film ran for only a few weeks. Still, the Viennese Arbeiter-Zeitung, although critical of a “not-too-logical plot”, praised the film’s “masterful” depiction of a “time out of joint” and the city’s atmosphere of “insecurity, poverty and post-war immorality”. Orson Welles dominates the film both by his presence and his absence. He was difficult to pin down, even for his brief appearances. Carol Reed used the time shooting at night, while waiting for Welles to show up, to experiment with tilted cameras and surreal shadows in narrow, gleaming nocturnal streets that became one of the film’s hallmarks.[4] Upon its release in Britain and America, the film received overwhelmingly positive reviews. Critics today have hailed the film as a masterpiece. The film has a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes with an average rating of 9.3/10 and the following consensus: “This atmospheric thriller is one of the undisputed masterpieces of cinema, and boasts iconic performances from Joseph Cotten and Orson Welles“[2].

Academy Award

The Third Man won the Academy Award for Best Cinematography (Black and White), and was nominated for Best Director and Best Film Editing. The film was named Best Film at the 1949 Cannes Film Festival. The Third Man also won considerable praise for Anton Karas’ score, which is played on a zither throughout the film.[5] Besides its top ranking in the BFI Top 100 British films list, in 2004 the magazine Total Film ranked it the fourth greatest British film of all time. The film also placed 57th on the American Film Institute‘s list of top American films in 1998, though the film’s only American connections were its executive co-producer David O. Selznick and its actors Orson Welles and Joseph Cotten.

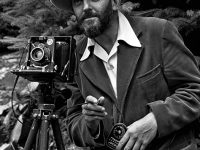

This is Orson Welles Lecture, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Third Man at IMDB

- [2] The Third Man at RottenTomatoes

- [3] Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, SciHi Blog, May 1, 2014.

- [4] Philippe Frence: The Third Man review – a near-perfect work, at The Guardian, August 2, 2015.

- [5] The Third Man, at The American Film Institute, Catalogue of Feature Films

- [6] Patrick Sawer: How the Third Man -Britain’s greatest film -almost went unmade, The Telegraph, 28 August 2016.

- [7] This is Orson Welles Lecture with Peter Bogdanovich, NewLondonBandTube @ youtube

- [8] The third Man on Wikidata

- [9] “Harry in the shadow”. The Guardian. 10 July 1999.

- [10] “‘The Third Man’ as a Story and a Film”. The New York Times. 19 March 1950.

- [11] Riegler (2020). “The Spy Story Behind The Third Man”. Journal of Austrian-American History. 4: 1–37.

- [12] Moss, Robert (1987). The Films of Carol Reed. New York: Columbia University Press.

- [13] Timeline for Orson Welles, via Wikidata