Theodor Fontane (1819-1898)

On September 20, 1898, German novelist and poet Theodor Fontane passed away. Fontane is regarded by many as the most important 19th-century German-language realist writer.

A Hugenot Family in Neuruppin

Theodor Fontane was born in Neuruppin, a town 30 miles northwest of Berlin, into a Huguenot family as son of the pharmacist Louis Henri Fontane. At the age of sixteen he was apprenticed to an apothecary. His further education was in Leipzig where he came into contact with the progressives of the Vormärz.

“Happiness consists in standing where one belongs by nature; even the question of virtue and morals fades away beside it. “

– Theodor Fontane, Letter to Gustav Karpeles, April 3, 1879;

Sibling Love and further Literary Efforts

Fontane’s first published work, the novella Geschwisterliebe (Sibling Love), appeared in the Berlin Figaro in December 1839, but did not receive promising reviews. In 1840 he accepted a job as an assistant pharmacist in Burg (near Marburg). During that time he also wrote his first poems. A seizure with typhoid fever made him return to his father’s shop in the provincial town of Letschin in the Oderbruch region. Fleeing its provincial atmosphere, Fontane published articles in the Leipzig newspaper Die Eisenbahn and translated Shakespeare. In 1843, he joined a literary club in Berlin called Tunnel über der Spree (Tunnel over the River Spree) where he came into contact with many of the most renowned German writers, including Theodor Storm, Joseph von Eichendorff and Gottfried Keller.

First Class Pharmacist

In March 1847 Theodor Fontane received his license as a “first class pharmacist”. In 1848 Fontane fought as a revolutionary in the so-called barricade street battles. During this time, he wrote four rather radical texts for the journal “Berliner Zeitungshalle”. At about the same time, he received a job in the Behtanien hospital. On September 30, 1849 Theodor Fontane decided to give up his job as a pharmacist and work as a freelance writer.[2]

Travels to England

Two trips to England, one (1852) to study ballad origins and a longer sojourn (1855-1859) as an attaché of the Prussian embassy, were followed by an editorial appointment on a conservative Berlin newspaper, Kreuzzeitung, a post that Fontane held until 1870. [3] Fontane’s books about Britain include Ein Sommer in London (1854), Aus England, Studien und Briefe (1860) and Jenseits des Tweed, Bilder und Briefe aus Schottland (1860). The success of the historical novels of Walter Scott had helped to make British themes much en vogue on the continent. Fontane’s Gedichte (1851) and ballads Männer und Helden (1860) tell of Britain’s former glories.

Hikes through the Mark Brandenburg

“If you want to travel in the Mark, you must first bring love for “country and people”, at least no bias. He must have the good will to find the good, instead of killing it by crotish comparisons.”

– Theodor Fontane in the preface to the second edition: “Wanderungen durch die Mark Brandenburg (1862-1888)

His post made possible considerable travel, notably described in the Wanderungen durch die Mark Brandenburg (Hikes through the Mark Brandenburg, 1862-1882), which reflect his fascination with the countryside surrounding Berlin and in which he transposed his former fascination with British historical matters to his native soil. In 1870, he quit his job at the Kreuzzeitung and became drama critic for the liberal Vossische Zeitung, a position he held until retirement. As a correspondent during the Franco-Prussian War, he was captured and narrowly escaped execution as a spy. In the postwar period he became, and remained for nearly 20 years, the theater critic of the Vossische Zeitung in Berlin.[3]

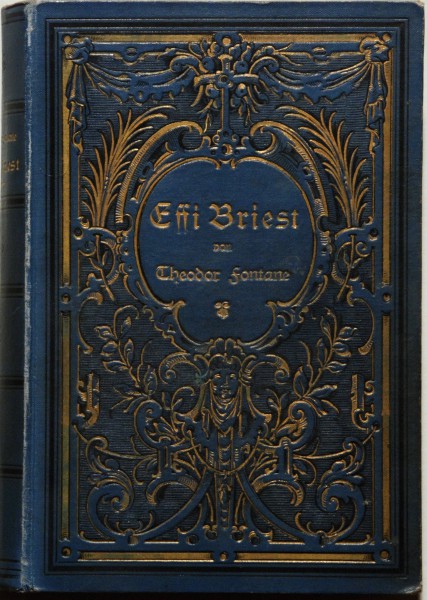

Theodor Fontane, Effie Briest, Philipp Reclam jun. Stuttgart (1894)

Famous Novels

At the age of 57 Fontane finally set to work in the genre for which he is remembered: the novel. A fine historical romance, Vor dem Sturm (Before the Storm, 1878) was followed by a series of novels of modern life, notably L’Adultera (Woman Taken in Adultery, 1882), which was considered so risqué that it took Fontane two years to find it a publisher. In his novels Irrungen, Wirrungen (Trials and Tribulations, 1888), Frau Jenny Treibel (1892) and Effi Briest (1894–95), he found his own tone, yielding insights into the lives of the nobility and of the common man. “Marriage is order,” Fontane believed, and without preaching he demonstrates the inevitably unhappy consequence when this “law” is flouted.[3]

Final Years – The Stechlin

His achievement there was later described as poetic realism. In Der Stechlin (written 1895–97), his last completed novel, Fontane adapted the realistic methods and social criticism of contemporary French fiction to the conditions of Prussian life. Fontane is no reformer but a mildly amused, somewhat reserved, and keen-eyed observer to whom “society” represents a manifestation of a principle of order.[3] In 1892 he fell ill with severe brain anemia. In order to distract himself, he followed his doctor’s advice and wrote down his childhood memories. Fontane was writing incessantly until he died in Berlin on September 20, 1898.[2]

Theodor Fontane’s Work

Fontane is regarded as the outstanding representative of poetic realism in Germany. In his novels, most of which were written after the age of 60, he characterizes the characters by precisely describing their appearance, their surroundings and above all their manner of speech from a critical and loving distance. Typical is the depiction of a cultivated conversation in a closed circle (also known as a causerie), for example at a banquet – the characters follow social conventions and yet reveal their true interests, often against their will. Fontane often moves from a criticism of individuals to an implicit critique of society. All novels and novellas are told from an authorial gesture (authorial narrator). However, a personal moment also appears as a trick, especially in the character speech in dialogues (personal narrator). Another striking feature of Fontane’s writing style is his ironic humor. A characteristic stylistic device of Fontane’s is the light, noncommittal interspersion of important motifs in the narrative, often with immediate relativization and withdrawal, to which reference is made again later and which thus receive special emphasis. This stylistic device is particularly common in Effi Briest.

Hölderlin und Fontane | Helmut Bachmaier, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Theodor Fontane, German writer, at Britannica Online

- [2] Henri Theodor Fontane, at Art Directory

- [3] “Theodor Fontane.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004. Encyclopedia.com.

- [4] Works by Theodor Fontane at Project Gutenberg

- [5] Theodor Fontane Gesellschaft e.V.

- [6] Theodor-Fontane-Archiv Potsdam

- [7] Works by or about Theodor Fontane at Internet Archive

- [8] . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- [9] Theodor Fontane at Wikidata

- [10] Hölderlin und Fontane | Helmut Bachmaier, 2014, uni auditorium – wissen online @ youtube

- [11] Daniel Mendelsohn, “Heroine Addict: What Theodor Fontane’s Women Want”, in: The New Yorker, 7 March 2011.

- [12] Kurt Schreinert: Fontane, Theodor. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 5, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1961,, S. 289–293.

- [13] Richard Moritz Meyer: Fontane, Theodor. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Band 48, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1904, S. 617–624.

- [14] Timeline for Theodor Fontane, via Wikidata