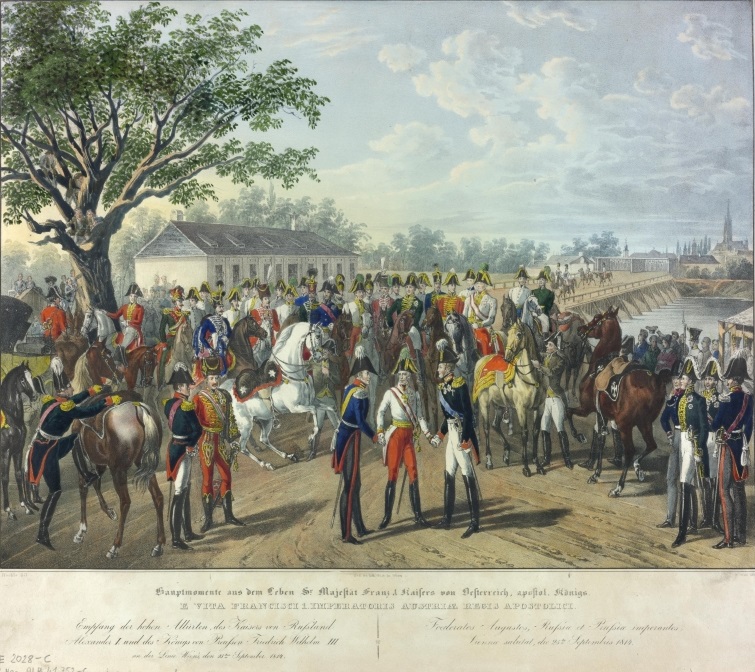

Emperor Franz I received Tsar Alexander I of Russia and King Frederick William III of Prussia, who had gathered to take part in the Congress of Vienna, at the Tabor Bridge on 25 September 1814.

On September 18, 1814, the Congress of Vienna began with ambassadors of many European states chaired by Austrian statesman Klemens Wenzel von Metternich with the objective to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars, and the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire. Its result was a redrawing of Europe’s political map and its effects still last until today.

The End of the War

After the fall of Napoleon in the spring of 1814, the First Paris Peace ended the war between the powers of the Sixth Coalition and the French government, the restored Bourbon monarchy under Louis XVIII. According to Article 32 of this Peace Treaty, a Congress was to meet in Vienna to decide on a permanent European post-war order. All states involved in the war were invited. The winning kings and their ministers met in London before the congress started in fall 1814. The Congress began in Vienna in the autumn of 1814 and was attended by delegations from almost all the states and powers of Europe. From September 1814 to June 1815, Vienna became the political centre of the continent, and above all the venue, the Foreign Ministry (later also the State Chancellery) in the Palais am Ballhausplatz, the official seat of Metternich. The event was hosted by Emperor Franz I of Austria.

Establishing a Political Balance

First, the congress’ political outcome was very little due to the amount of entertainment the statesmen were encountered with. But then, several commissions were established to deal with the various issues, starting with groups for German, for French and for European problems. Meetings were not always as delightful as the many dances and dinners the Austrian hosts invited their guests to. During the congress, several conflicts evolved or deepened before solutions could be found. Still, the European powers had the same idea of establishing a political balance on the continent to prevent further wars.

The most important Players

Metternich’s most important opponent was Tsar Alexander I. In addition, the British envoy Castlereagh and the representative of the defeated France, Talleyrand, who had considerable influence under both the old and the new French regime, played the most important roles. Prussia was represented by Karl August von Hardenberg and Wilhelm von Humboldt and was able to record considerable gains on land (above all in the Rhineland and opposite Saxony) and expand its political position.

Contradicting Goals

Realizing these ideas however meant collisions of different political goals of single countries. Klemens Wenzel von Metternich preferred a central European power led by Austria while Russia aimed to receive a great part of Poland’s territorial. Britain in contrast tried to decrease Russia’s power in Europe and the French aimed to prevent a Prussian union to improve its own power. The frequently drawn picture of harmony does not exist in this way: in fact, the clashes of interests between the (main) negotiating partners intensified significantly in the course of the Congress. With all these individual goals and only little room for compromises, Europe feared that no solution could be found. One of the major conflicts between Austria, Prussia and Russia was the territories of Poland and were only able to be solved during the beginning of 1815. There was agreement on the creation of a European system of equilibrium to prevent future wars. The practical implementation of the latter objective in particular, however, initially collided with the various power-political interests. Metternich’s goal, for example, was an Austria-led Central Europe that would form a counterweight to the wing powers of France and Russia. Russia’s main goal, however, was to win most of Poland. The tsar was toying with the idea of making Poland a model of a constitutional state. The British envoy, like Metternich, strove for a conservatively determined Europe and at the same time wanted to prevent a further expansion of Russia’s power as far as possible. In order to protect its position of great power, the French delegation also fought against the unification efforts in Germany. Prussia, on the other hand, wanted to strengthen its own position by acquiring all of Saxony and a Prussian-Austrian hegemony in Germany. However, the interests of the smaller German states and Austria were opposed to this.

Restauration

The Congress worked according to five overriding principles, some of which are, however, the subsequent construction of historians. In this context, the concept of legitimacy refers to the liquidation of the Napoleonic state system and the restoration of the old dynasties (Bourbons, Guelphs, etc.). When Talleyrand, of all people, emphasised the principle of legitimacy, he was primarily concerned with recognising France as an equal power and thus overcoming its status as a loser of war. The principle of restoring pre-revolutionary political and social conditions also belongs in this context. The restoration should not go so far as to reverse all changes that have occurred since 1789, but it should put a stop to all future revolutionary efforts. This included not only the liberal but also the national movements of the time.

The Result

The congress resulted in several territorial rearrangements. Austria’s overall growth was only little while Prussia gained the northern part of Saxony but lost parts from Poland. Switzerland received Basel and several areas around Geneva, but had to give up its hopes on Veltlin, Chiavenna and Bormio. France’s biggest success during the meetings was probably its overall acceptance as a major power of Europe. Denmark had to give its Norwegian territory to Sweden due to their previous support of Napoleon’s troops. Zar Alexander received major parts from Poland. The German Confederation was created with Austria as its leading power and it was manifested in a constitution in June, 1815. The overall results of the congress were combined and signed in the ‘Final Act’ on June 9, 1815.

Aftermath

The Congress of Vienna had taken forward-looking decisions for the circumstances of the time, especially at the supranational level. Thus, under British pressure, the outlawing of slavery was enforced in Article 118 of the Congress Act. In addition, an agreement was reached on the freedom of international river navigation and a Central Commission for Navigation on the Rhine was set up. A binding regulation of the law on diplomatic missions put an end to the usual disputes between diplomats over rank. In general, the statesmen were admired by later historians for being able to find solutions for serious problems in order to prevent another major war, which they successfully did for another 100 years. But still, revolutions in later years were not foreseen and many criticize the procedure of the negotiations, leaving many aspects like the people of their nations. Also, only four leading powers were able to make the major decisions, wherefore smaller countries had no further chance to really speak up and demonstrate their ideas.

The Congress of Vienna 1814-1815: Making Peace after Global War (Part 1), [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Great European Treaties of the Nineteenth Century

- [2] Final Act of the Congress of Vienna at Wikisource

- [3] Map of Europe in 1815

- [4] “The Congress of Vienna at the Victorian Web

- [5] The Congress of Vienna at Wikidata

- [7] Treaty of Vienna (Seventh Coalition) at Wikisource

- [8] Declaration at the Congress of Vienna at Wikisource

- [9] The Congress of Vienna 1814-1815: Making Peace after Global War (Part 1), Columbia University @ youtube

- [10] Timeline of Peace Treaties, via DBpedia and Wikidata