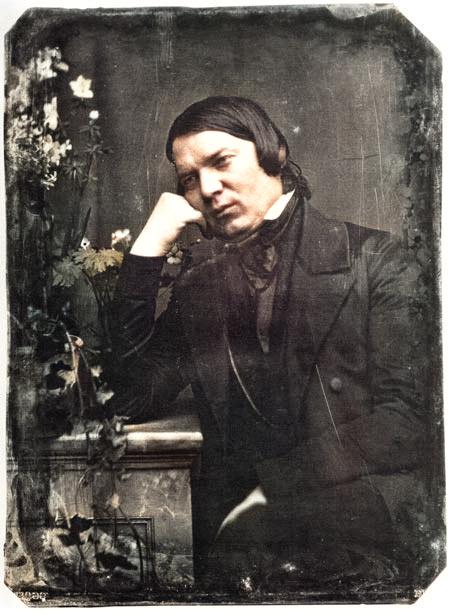

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) in an 1850 daguerreotype

On June 8, 1810, German composer and influential music critic Robert Schumann was born. Schumann is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career as a virtuoso pianist, but a hand injury ended this dream of becoming one of Europe‘s finest pianists. Schumann then focused his musical energies on composing.

“Look deeply into life, and study it as diligently as the other arts and sciences.”

― Robert Schumann, Advice to Young Musicians

The Musical Education of Robert Schumann

The musical education of Robert Schumann began at the age of six. He first studied the piano and in 1827, he came under the musical influence of the Austrian composer Franz Schubert and the literary influence of the German poet Jean Paul Richter. In the same year, Schumann began to compose own songs. At the University of Leipzig, the musician began to study law but spent most of his time composing, improvising at the piano. It is also believed that Schumann attempted to write novels. After a while, Robert Schumann abandoned law completely.

Abandoning his Career as Virtuoso and Focusing on Composition

Opus 1, the Abegg Variations for piano, was published in 1831. Due to an accident of his right hand, the artist had to abandon his career as a virtuoso, but let him focus on his compositions. Schumann made great achievements during the 1830s. Papillons and Carnaval, and the Études symphoniques were composed in that period. He wrote the great Fantasy in C Major for piano and edited the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Journal for Music), a periodical that he had helped to found in 1834 and of which he had been editor since early 1835. Two years later, Schumann composed the Davidsbündlertänze, Phantasiestücke. In this creative period, he also managed to compose Kinderszenen, Kreisleriana, Arabeske, and more. He wrote most of Faschingsschwank and found some manuscripts by Franz Schubert, including that of the Symphony in C Major. Some of his most important works, Myrthen, the two Liederkreise on texts by Heinrich Heine and Joseph Eichendorff, and several more were composed around the 1840s.

Clara

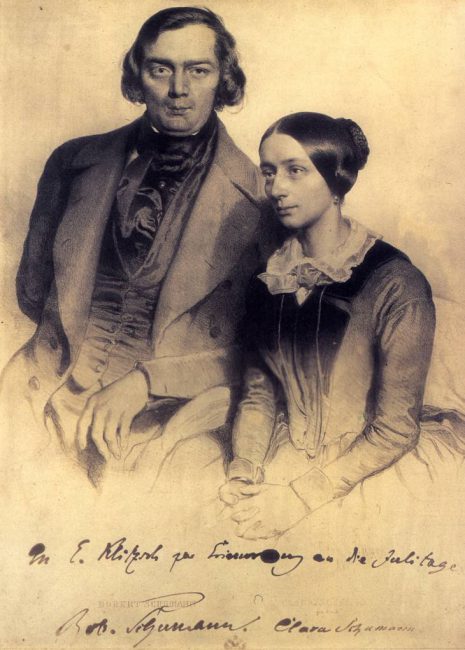

In 1840 Robert Schumann also married Friedrich Wieck‘s daughter Clara, against the wishes of her father, following a long and acrimonious legal battle, which found in favor of Clara and Robert. Clara Wieck met Robert Schumann in 1828, at the age of about eight and a half. From October 1830 Schumann lived with the Wiecks for a year at the age of twenty, when he was taught by Clara’s father. When Clara Wieck was 16, they came closer. Clara’s father, however, was by no means willing to award them to the young man who had no profession and could no longer even become a pianist, because impairments of the right middle finger and the right hand, which Robert described as “weakness” and “paralysis”, had prematurely ended this career. Even the fact that Robert Schumann was quite successful as a music editor and had founded the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik with him could not change his mind. In September 1839, Robert Schumann and Clara Wieck finally filed a lawsuit with the court in Leipzig, requesting that either father Wieck be obliged to agree to the planned marriage, or that consent be granted ex officio. The proceedings were delayed, not least due to the intervention of Friedrich Wieck. On August 1, 1840, the court finally approved the marriage, which was concluded on September 12, 1840 in the Gedächtniskirche Schönefeld near Leipzig. Clara also composed music and had a considerable concert career as a pianist, the earnings from which, before her marriage, formed a substantial part of her father’s fortune.

Robert and Clara Schumann, lithograph by Eduard Kaiser with personal dedication of the couple, 1847

Years of Great Productivity

1840 was a year of great productivity, in which about half of his entire song production was written (including Liederkreis op. 39 and Dichterliebe op. 48); the year is therefore often referred to as his “song year”. In 1841 Schumann composed his Symphony No. 1 in B flat major, the Spring Symphony. As money worries grew, Clara Schumann went on a concert tour again in January 1844, including to Russia, which earned her 6000 Taler. Schumann accompanied her, in the eyes of Clara’s admirers, often only as the husband of a pianist known throughout Europe. Schumann’s 1st Symphony was performed in a private concert in Saint Petersburg. In 1842 he wrote several chamber works and Das Paradies und die Peri was created one year later. During that time, the newly founded Leipzig Conservatory had been opened with Mendelssohn Bartholdy as director and Schumann as professor of “piano playing, composition, and playing from score”.[6] He began symphony, No. 2 in C Major in 1845 and it took him about 10 years to finish. In December 1849, Schumann accepted a post of municipal director of music at Düsseldorf, but lost the position due to to his shortcomings as a conductor. However, Schumann infected the enthusiasm of the Rhinelanders: In 1850 he composed his 3rd Symphony in E-flat Major, the so-called Rheinische, in addition to many other new works in November and December.

The End of a Career

“To send light into the darkness of men’s hearts – such is the duty of the artist.”

—Robert Schumann

A scandal in an orchestra rehearsal for the first subscription concert of the 1853/54 winter season led to Schumann being asked by the committee of the Musikverein to conduct only his own works and to hand over the direction. Schumann then resigned on October 1, 1854 and did not appear at the conductor’s podium for the concert of November 10, 1853. Now he also stopped composing. On February 10, 1854, Schumann’s mental ailments increased in leaps and bounds. He complained above all of “hearing affections”. Sounds, chords, whole musical pieces raged in his head and robbed him of his sleep. It is assumed that Robert Schumann had contemplated suicide several times. He asked to be taken to a lunatic asylum, and the next day he attempted suicide by drowning. He was transferred to the private asylum at Endenich, near Bonn, where he lived for nearly two and a half years. Robert Schumann died alone on July 29, 1856, at age 46. Clara Schumann survived her husband by 40 years.

A Literary-Musical Double Talent

Robert Schumann had a literary-musical double talent. Poems, artistic prose, drafts and musical compositions stood side by side on an equal footing at a young age. It was only after 1830 that music became the centre of his concept of life, and he saw himself as a sound poet. In his compositions as well as from 1834 at the latest with the help of his literary works he strived for a seminal, poetic music, whereby he distanced himself from Franz Liszt‘s programme music. His works were considered too difficult by many contemporaries. For a long time the bon mot that he began as a genius and ended as a talent, and his late works were marked by his illness leading to an insane asylum. But with the discussion of late works in musicology since the end of the 20th century, the view has changed. Schumann’s complete works are now widely recognized and he is considered one of the great composers of the 19th century.

Fionnuala Moynihan, Clara Schumann (1819-1896) – The Unsung Heroine of Romanticism, [8]

- [1] Robert Schumann at Britannica

- [2] Website about Robert Schumann

- [3] Franz Schubert – Misjudged Pioneer of the Romantic Music, SciHi Blog

- [4] Heinrich Heine – Famous Poetry with Radical Political Views, SciHi Blog

- [5] Franz Liszt – Rockstar of the 19th Century, SciHi Blog

- [6] Felix Mendelssohn – Child Prodigy of the Romantic Era, SciHi Blog

- [7] Robert Schumann at Wikidata

- [8] Fionnuala Moynihan, Clara Schumann (1819-1896) – The Unsung Heroine of Romanticism, Gresham College @ youtube

- [9] Ostwald, Peter (1985). Schumann, The Inner Voices of a Musical Genius. Northeastern University Press

- [10] Worthen, John (2007). Robert Schumann: Life and Death of a Musician. Yale University

- [11] Bodsch, Ingrid. “Schumann network”. Stadtmuseum, Bonn; Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media.

- [12] Timeline for Robert Schumann, via Wikidata