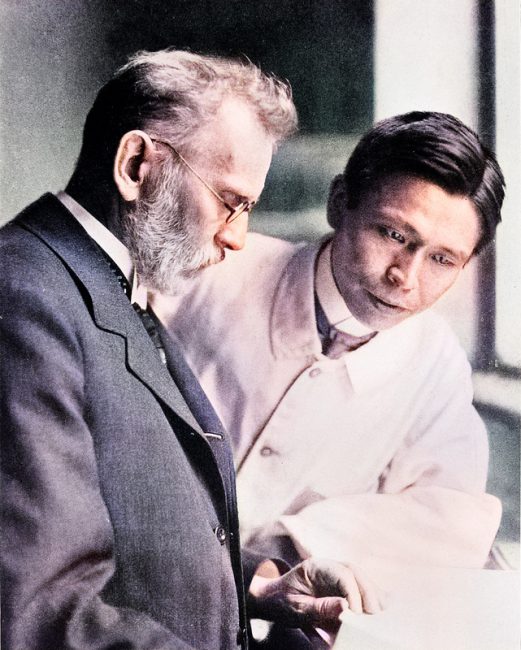

Paul Ehrlich and Sahachiro Hata

On March 14, 1854, German Jewish physician Paul Ehrlich was born. Ehrlich made significant contributions in the fields of hematology, immunology, and chemotherapy. He invented the precursor technique to Gram staining bacteria. The methods he developed for staining tissue made it possible to distinguish between different type of blood cells, which led to the capability to diagnose numerous blood diseases.

“In order to pursue chemotherapy successfully we must look for substances which possess a high affinity and high lethal potency in relation to the parasites, but have a low toxicity in relation to the body, so that it becomes possible to kill the parasites without damaging the body to any great extent. We want to hit the parasites as selectively as possible. In other words, we must learn to aim and to aim in a chemical sense. The way to do this is to synthesize by chemical means as many derivatives as possible of relevant substances.”

— Paul Ehrlich, (1909)[10]

Paul Ehrlich – Early Years

Paul Ehrlich was the second child of Rosa and Ismar Ehrlich, an innkeeper and distiller of liqueurs and the royal lottery collector in Strehelen, a small town Lower Silesia, now in Poland. He attended the Maria-Magdalenen-Gymnasium in Breslau and became fascinated by the process of staining microscopic tissue substances. He studied medicine at the universities of Breslau, Strasbourg, Freiburg im Breisgau and Leipzig, receiving his doctorate in 1882. Afterwards, he began working at Charité in Berlin as an assistant medical director under Theodor Frerichs, the founder of experimental clinical medicine, focusing on histology, hematology and color chemistry.

Travel to Egypt and a Cure for Tuberculosis

Ehrlich traveled to Egypt in the mid 1880s in order to find a cure for tuberculosis. He established a private medical practice and a laboratory in Berlin-Steglitz. In 1891, Paul Ehrlich received was asked by Robert Koch to join the staff at his Berlin Institute of Infectious Diseases.[4] In 1896 a new institute was established for Ehrlich’s specialization, the Institute for Serum Research and Testing, whose director he became. Later on, Paul Ehrlich became the director of the Georg Speyer House in Frankfurt, a private research foundation affiliated with his institute.

The Need of the Organism for Oxygen

As his habilitation thesis, Ehrlich submitted The Need of the Organism for Oxygen in 1885. In it, he introduced the new technology of in vivo staining. Through injecting the dyes alizarin blue and indophenol blue into laboratory animals, he found that after their death, various organs had been colored to different degrees. He then theorized that all life processes can be traced to processes of physical chemistry occurring in the cell.

Methylene Blue and Malaria

Further, Paul Ehrlich came to believe that methylene blue could be particularly suitable for staining bacteria. He believed that since the parasite family of Plasmodiidae can be stained with methylene blue, it could possibly be used in the treatment of malaria. After treating two patients in Berlin-Moabit successfully, Paul Ehrlich obtained methylene blue from the company Hoechst AG, which ended up in a long collaboration with this company.

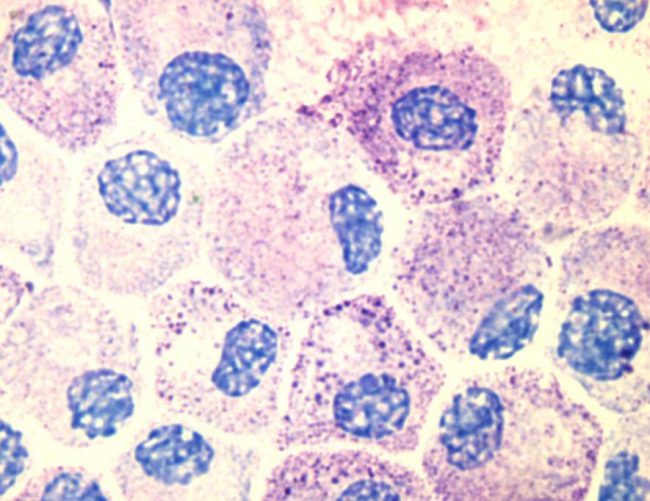

Photo of cultured mast cells at 100X using an oil immersion lens and an olympus digital camera. The cells are stained with Tol Blue, and might appear slightly degranulated as they were activated using an artificial antigen during the course of an experiment.

Salvarsan and Syphilis

Paul Ehrlich continued his research on methylene blue and started looking for an agent which was as good as methylene blue but without its side effects. He thought there must be chemical pharmaceuticals which would have just as specific an effect on individual diseases and he wanted to find a “Therapia sterilisans magna“, a treatment that could kill all disease pathogens. The scientist systematically tested chemical compounds and he discovered that for instance Arsenophenylglycine had a large therapeutic effect. In 1909, he also discovered a compound that combatted the causes of syphilis and had only little side effects. It was marketed as Salvarsan starting from 1910 which was a great success. It turned out to be the most effective drug for treating syphilis until penicillin became available.

Cancer Research

The cancerous disease of Princess Victoria, the widow of the German Emperor Friedrich II, had received much public attention. Thereby, Ehrlich had received from the German Emperor Wilhelm II a personal request to devote all his energy to cancer research. Among the results achieved by Ehrlich and his research colleagues was the insight that when tumors are cultivated by transplanting tumor cells, their malignancy increases from generation to generation. If the primary tumor is removed, then metastasis precipitously increases. Ehrlich applied bacteriological methods to cancer research. In analogy to vaccination, he attempted to generate immunity to cancer by injecting weakened cancer cells.

A Magic Bullet

Ehrlich reasoned that if a compound could be made that selectively targeted a disease-causing organism, then a toxin for that organism could be delivered along with the agent of selectivity. Hence, a “magic bullet” (magische Kugel, his term for an ideal therapeutic agent) would be created that killed only the organism targeted. The concept of a “magic bullet” has to some extent been realized by the development of antibody-drug conjugates (a monoclonal antibody linked to a cytotoxic biologically active drug), as they enable cytotoxic drugs to be selectively delivered to their designated targets (e.g. cancer cells).

A Theoretical Basis for Immunology

For providing a theoretical basis for immunology as well as for his work on serum valency, Ehrlich was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1908 together with Élie Metchnikoff.[6] Metchnikoff, who had researched the cellular branch of immunity, Phagocytosis, at the Pasteur Institute had previously sharply attacked Ehrlich.

Later Years

From 1911 until his death, Paul Ehrlich was a member of the Senate of the newly founded Kaiser Wilhelm Society. In 1911 he was awarded the Liebig medal of the German Chemical Society. Ehrlich, who had always considered lectures to be an annoying duty, was appointed full professor of pharmacology at the newly founded Frankfurt University in 1914. Paul Ehrlich rejected the elevation to nobility because he did not want to leave Judaism. On 17 August 1915, Ehrlich suffered a heart attack, which he succumbed to on 20 August.

Paul Ehrlich (1854-1915): A Century in Eternity, [9]

References and Futher Reading:

- [1] Paul Ehrlich Biography at the Nobel Museum

- [2] Paul Ehrlich at the New York Times

- [3] Paul Ehrlich and Salvarsan

- [4] Robert Koch and Tuberculosis, SciHi Blog, December 11, 2013.

- [5] Paul Ehrlich at Wikidata

- [6] Ilya Mechnikov and the Macrophages, SciHi Blog, May 16, 2015.

- [7] Works by or about Paul Ehrlich at Wikisource

- [8] Works by or about Paul Ehrlich at Internet Archive

- [9] Paul Ehrlich (1854-1915): A Century in Eternity, limewaveZ @ youtube

- [10] Paul Ehrlich, ‘Ueber den jetzigen Stand der Chemotherapie‘. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschagt, 1909, 42, 17-47. Translated in B. Holmstedt and G. Liljestrand (eds.), Readings in Pharmacology (1963), 286.

- [11] Timeline of Nobel Laureates of Medicine or Physiology, via DBpedia and Wikidata