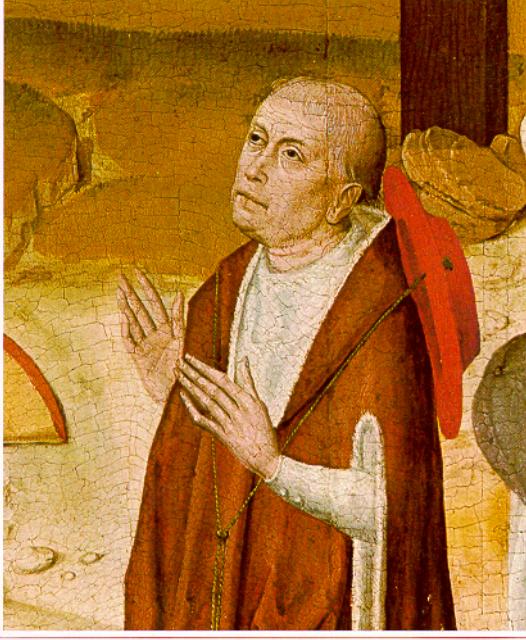

Nikolaus of Cusa (1401-1464)

On August 11, 1464, German philosopher, theologian, jurist, and astronomer Nikolaus of Cusa (in latin: Nicolaus Cusanus) passed away. He is considered as one of the first German proponents of Renaissance humanism. His best known work is entiteled ‘De Docta Ignorantia‘ (Of the Learned Ignorance), where also most of his mathematical ideas were developed, as e.g. the trial of squaring the circle or calculating the circumference of a circle from its radius.

“In God, absolute unity is absolute multiplicity, absolute identity is absolute diversity; absolute actuality is absolute potentiality.”

— Nikolaus of Cusa, De Docta Ignorantia (On Learned Ignorance) (1440)

Nikolaus of Cusa – Childhood and Legend

Nikolaus of Cusa or Kues (latinized as “Cusa”), was born at Cues, today’s Bernkastel-Kues, on the river Moselle, in the Archdiocese of Trier at about 1400 or 1401. His father, Johann Cryfts (Krebs) was a wealthy boatman. Nikolaus was one of his parents’ four children. The legend that Nicholas fled from the ill-treatment of his father to Count Ulrich of Mandersheid is doubtfully reported (the story being that Nicholas was only interested in books and annoyed his father by being unable to handle an oar), and has never been proved. Of his early education in a school of Deventer in the Netherlands nothing is known.

Heidelberg, Padua, and Cologne University

Nikolaus entered the Faculty of Arts of the Heidelberg University in 1416 as “a cleric of the Diocese of Trier”, studying the liberal arts. He seemed to have left Heidelberg soon afterwards, as he received his doctorate in canon law from the University of Padua in 1423. In Padua, he met made friends with the mathematician Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, afterwards a celebrated physician and scientist. It was in Padua that Nicholas learnt about the latest developments in mathematics and astronomy and, twenty years later, Nicholas dedicated two of his mathematical works to Toscanelli. He studied Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and, in later years, also Arabic though he was not a lover of rhetoric and poetry. Afterwards, aided by Otto of Ziegenhain, the Archbishop of Trier, Nikolaus entered the University of Cologne in 1425 as “a doctor of canon law” which it appears he both taught and practiced there.

Identifying Famous Forgeries

Nikolaus returned to his hometown and became secretary to the Prince-Archbishop of Trier, who appointed him canon and dean at the stift of Saint Florinus in Koblenz affiliated with numerous prebends. In 1427 he was sent to Rome as an episcopal delegate. The next year he travelled to Paris to study the writings of Ramon Llull.[6] Nikolaus acquired great knowledge in the research of ancient and mediæval manuscripts as well as in textual criticism and the examination of primary sources. In 1433 he identified the Donation of Constantine, i.e. Roman imperial decree by which the emperor Constantine the Great supposedly transferred authority over Rome and the western part of the Roman Empire to the Pope, as a fake and also revealed the forgery of the Pseudo-Isidorian Decretals, which aimed to defend the position of bishops against metropolitans and secular authorities. He advocated a reform of the Julian calendar and the Easter computus, which however was not realised until the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in 1582.[7]

De Concordantia Catholica

In 1428 and 1435 Nikolaus was offered positions teaching canon law at the University of Louvain, but he turned them down to remain in church administration. Ordained a priest sometime during the 1430s, Nikolaus first gained wider notice for his work as a conciliarist at the Council of Basel, where he wrote De concordantia catholica (1433), arguing for the authority of the council over that of the Pope. Starting from the basic idea of harmony, Nicholas developed a general church doctrine in the first book, explained his council theory and his ideas for reforming the church and councils in the second book, and presented his state theory and his ideas for reforming the empire in the third book. In 1437 Nikolaus was part of an embassy sent to Constantinople which was attempting to bring the Eastern Orthodox Church into union with the Western Catholic Church again. But, the reunion achieved at this conference turned out to be very brief.

The Learned Ignorance

He reported that, during the voyage home, the insights of De docta ignorantia (1440) came to him as a kind of divine revelation. Earlier scholars had already discussed the question of “learned ignorance”. Augustine of Hippo [8] among others, stated “Est ergo in nobis quaedam, ut dicam, docta ignorantia, sed docta spiritu dei, qui adiuvat infirmitatem nostram“, explaining the working of the Holy Spirit among men and women, despite their human insufficiency, as a “learned ignorance”. For Nikolaus of Cusa docta ignorantia means that since mankind can not grasp the infinity of a deity through rational knowledge, the limits of science need to be passed by means of speculation. This mode of inquiry blurs the borders between science and ignorance. In other words, both reason and a supra-rational understanding are needed to understand God, which leads to a union of opposites.

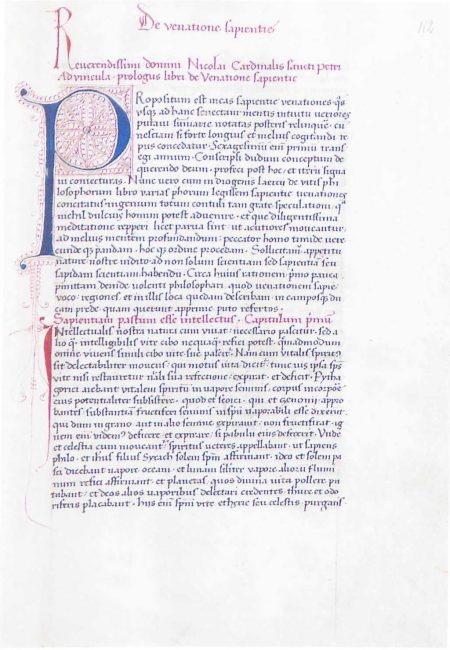

Nikolaus of Cusa, De venatione sapientiae (“On the Hunt for Wisdom”), Bernkastel-Kues, St. Nicholas Hospital/Cusanusstift, Sign. Cod. Cus. 219, fol. 112r

Cardinal and the Conflict with Duke Sigismund

Nikolaus continued as a papal legate to Germany from 1438–48. Named cardinal in 1446 by Eugenius IV, Cusanus was elevated to that position in 1448 by Nicholas V and was sent to Germany in 1451 as papal legate to reform the church. In 1452 Nikolaus began active administration as bishop of Brixen, but his attempts at reform led to threats and clashes with Duke Sigismund of Austria. Many of his over two hundred sermons date from this time in Brixen, though his reform efforts there and earlier in Germany mostly failed. The duke imprisoned Nicholas in 1460, for which Pope Pius II excommunicated Sigismund and laid an interdict on his lands.

Later Years

Nikolaus spent the last years of his life as Curia Cardinal in the Papal States, where he worked out a concept for reforming the church leadership that had no consequences. He expressed his bitterness with the words:

“I do not like anything that is done here at the Curia; everything is corrupt, nobody does his duty. … When I finally speak of reform in the Consistorium, I will be laughed at“.

From 1461 he was seriously ill; among other things he suffered from gout. In the summer of 1464, as part of the crusade project against the Turks carried out by Pius II, Nicholas was commissioned to look after a group of 5,000 destitute crusaders, some of them ill, who wandered between Rome and Ancona, from where the fleet was to set sail. On the way, he died in Todi on August 11, 1464.

“Now law ought to be made by all those who are to be bound by it, or by a majority in an election, because it is for the good of the community, and what affects all ought to be decided by all, and a common decision can only be reached by the consent of all, or of a majority.”

— Nikolaus of Cusa, De concordantia catholica (The Catholic Concordance) (1434)

The Works of Nikolaus of Cusanus

Nicholas wrote more than 50 writings, about a quarter of them in dialogue form, the rest usually as treatises, further about 300 sermons as well as an abundance of files and letters. His works can be divided into three main groups according to their content: Philosophy and theology, church and state theory, mathematics and natural science. His short autobiography, which he wrote in 1449, occupies a special position. The works of Nikolaus of Cusa were widely read, and his works were published in the sixteenth century in both Paris and Basel. Nonetheless, there was no Cusan school, and his works were largely unknown until the nineteenth century, though Giordano Bruno quoted him. Gottfried Leibniz was considered to have been influenced by Cusanus. In the early twentieth century, Nikolaus of Cusa was entiteled as the ‘first modern thinker’.

Natural Sciences and Mathematics

“Mathematics is a purely human creation, which we dominate because we created it ourselves.”,

Nikolaus of Cusa

The mathematical and scientific work of Cusanus is characterized above all by his interest in the theory of science and his metaphysical-theological questions; he wants to lead from mathematical to metaphysical insights. He deals with analogies between mathematical and metaphysical thinking in writings such as De mathematica perfectione (“On mathematical perfection“, 1458) and Aurea propositio in mathematicis (“The golden proposition in mathematics“, 1459). De mathematicis complementis (“On mathematical Complements“, 1453) is regarded as his major mathematical work. He dealt with the problem of squaring the circle and the calculation of the circumference of a circle in several writings, including De circuli quadratura (“On Squaring the Circles“, 1450), Quadratura circuli (“Squaring the Circle“, 1450), Dialogus de circuli quadratura (“Dialogue on squaring the circle“, 1457) and De caesarea circuli quadratura (“On empirially squaring the circle“, 1457). Also in De mathematica perfectione Nicholas deals with this problem. He considers a circular quadrature only approximately possible and suggests a procedure for it. With his dialogue Idiota de staticis experimentis (“The layman on experiments with the scales“, 1450), he is one of the pioneers of experimental science. He suggests, for example, that the pulse frequency should be measured using a water meter, and points out that the question of whether alchemical material transformations can be realized in practice can only be answered by experimental quantitative research.

Daniel Burke, Nicholas of Cusa [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Nikolaus of Cusa in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- [2] Nikolaus of Cusa at MacTutor’s History of Mathematics

- [3] Nikolaus of Cusa at Britannica Online

- [4] Nikolaus of Cusa at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- [5] Nicholas of Cusa at Wikidata

- [6] Ramon Llull and the Tree of Knowledge, SciHi Blog

- [7] The Days That Never Happened – The Gregorian Calendar, SciHi Blog

- [8] Saint Augustine’s Confessions, SciHi Blog

- [9] Daniel Burke, Nicholas of Cusa, LaRougePAC Science @ youtube

- [10] Works by or about Nicolaus Cusanus at Internet Archive

- [11] History of Modern Philosophy: From Nicolas of Cusa to the Present Time, Richard Falckenberg, 1893

[12] Timeline of Nicholas of Cusa, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #52 | Whewell's Ghost