The Voynich manuscript – a famous case in the history of cryptography

In 1912, Polish-born antiquarian and bibliophile Wilfrid Voynich bought a mysterious illustrated codex hand-written in an unknown writing system that may have been composed in Northern Italy during the Italian Renaissance. The eponymous Voynich manuscript has been studied by many professional and amateur cryptographers, but no one has yet succeeded in deciphering the text. Therefore, it has become a famous case in the history of cryptography.

A Strange Manuscript

The manuscript counts about 240 pages in total, but it is assumed that several pages are missing. The text was written from left to right and patterns similar to those of natural languages were revealed by statistical analysis. Still, it was found that the manuscript’s “language” is quite unlike European languages since there are no words with fewer than two letters or more than ten and it seems to be more repetitive than typical European languages. Another difficult aspect is, that the lettering resembles European alphabets of the late 14th and 15th centuries, but the words do not seem to make sense in any language. It was found out that the manuscript probably consists of six sections and except the last one, every section and even almost every page contains various illustrations.

Structure of the Manuscript

The sections were examined concerning their content and given conventional names. The so called herbal section contains at least one plant on each page, which are not unambiguously identifiable. In the astronomical section, many diagrams can be found with suns, moons, and stars. Further sections are probably of biological, cosmological, and pharmaceutical purpose.

Potential Timeline

It was not until 2009 that institutes in Chicago and Arizona examined the smallest samples from four different sides. In a radiocarbon analysis the age of the parchment used could be determined with high probability to be between 1404 and 1438. Presumably all pages are of the same origin Furthermore, experts from the McCrone Research Institute in Chicago have determined that the ink was not applied much later. It was also suggested that the book originally belonged to Emperor Rudolf II and that at some point, Athanasius Kircher owned the book as well. From the barely legible and probably not handwritten name entry Jacobj ‘a Tepenece on the first page of the manuscript it can be concluded – if it is genuine – that the Czech court pharmacist Jakub Horčický z Tepence had the copy in his hands for reading or was even its owner. Since his title of nobility is already used, this entry would have to have been made after 1608. In a letter found with the manuscript, its alleged author, the later owner Johannes Marcus Marci, writes that at that time Rudolf II of Habsburg, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, was rumoured to have been the owner of the manuscript after he had bought it from an unknown dealer for the then high sum of 600 ducats. Either Jakub Horčický was this dealer, or – and this theory is considered more likely – the manuscript was entrusted to him by Rudolf II for further analysis, as he was known as a successful chemist and pharmacist.

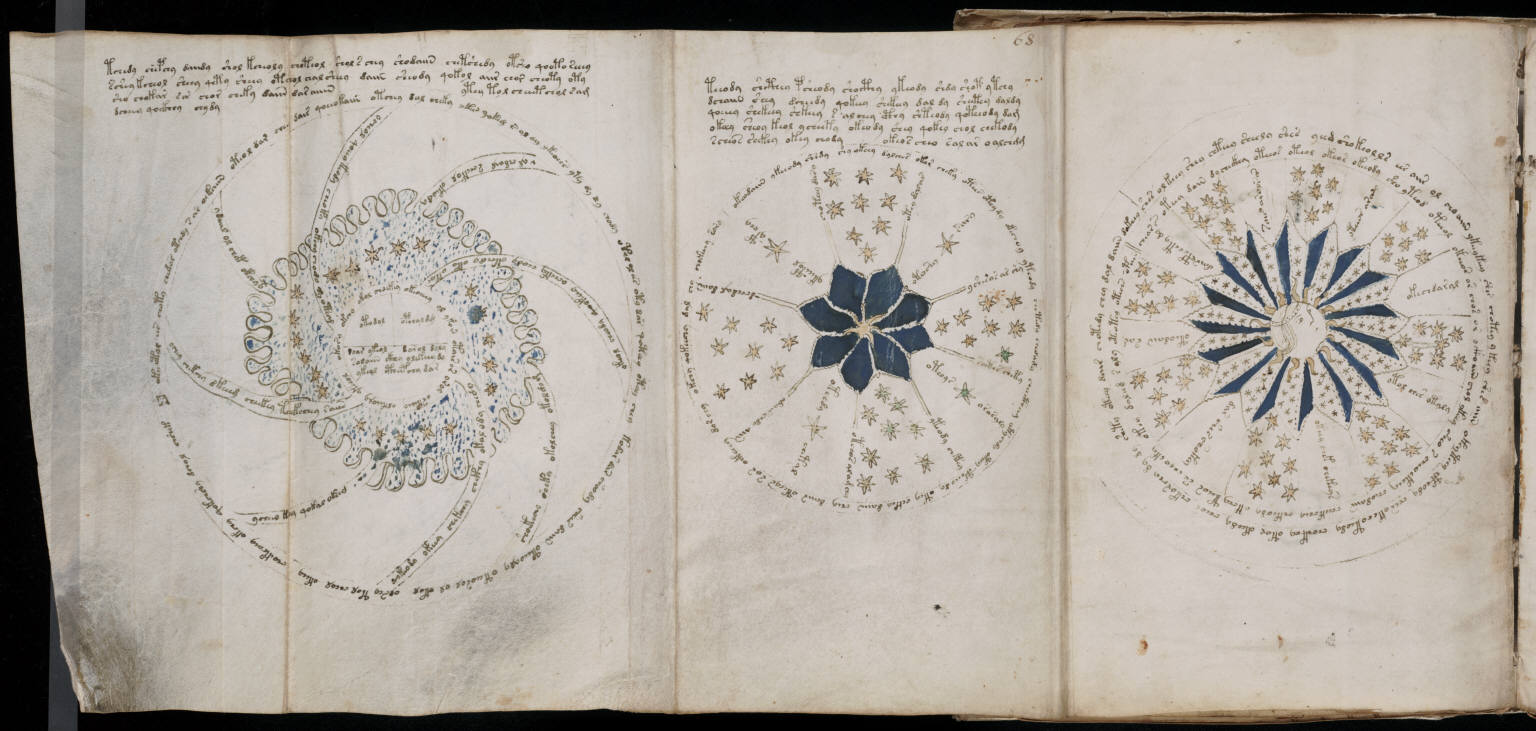

Page 68r from the mysterious Voynich manuscript, which is undeciphered to this day. This three-page foldout from the manuscript includes a chart that appears astronomical(looks like a creation for a sun,or “fusion core startup process”)

Futile Tries of Decipherment

According to the accompanying letter, the next known owner was the Bohemian scholar and alchemist Georg Baresch, who lived in Prague at the beginning of the 17th century. Baresch had tried to decipher the text, but had failed. He therefore turned to Athanasius Kircher,[4] a Jesuit universal scholar and a celebrity at the time, who allegedly succeeded in reading the hieroglyphic writing of the ancient Egyptians. That Kircher’s reading was completely erroneous only became clear after Champollion had successfully deciphered the hieroglyphics. In his time, however, Kircher was regarded as an expert in deciphering enigmatic texts, which is why Baresch sent him a copy of the manuscript texts together with a request for an expertise. However, Kircher seems never to have reacted to this request.

Further Owners until Voynich

What happened to the manuscript in the more than 200 years between 1666 and 1870 is still unknown. But as it was (according to Voynich) part of a library of the Jesuit Order, it can be assumed that the manuscript was, together with Kircher’s estate, in the possession of the Jesuit Order, thus first belonged to the library of the Collegium Romanum (today the Pontifical Gregorian University). It probably remained there until the Papal States were annexed by the troops of Victor Emanuel II in 1870 during the Risorgimento and ecclesiastical property was threatened with confiscation. The holdings of the Pontifical University Library were hastily transferred to the members of the faculty, as private property was not threatened by the Italian state. Among them was Kircher’s estate, which was given to the then General of the Order Pierre Jean Beckx. The Voynich manuscript belonged to this stock, according to an ex-libris of Beckx. Beckx’ “private library” finally became part of the book holdings of the Jesuit College Nobile Collegio Mondragone, founded in 1865 in the Villa Mondragone near Frascati. There it was probably discovered in 1912 by Wilfrid Michael Voynich, who claims to have bought it from the Jesuits together with about 30 other valuable manuscripts. When Wilfrid Voynich passed away, the manuscript was inherited by his widow and then changed the owners several times before it was donated to Yale University in 1969 where it was catalogued as “MS 408“.

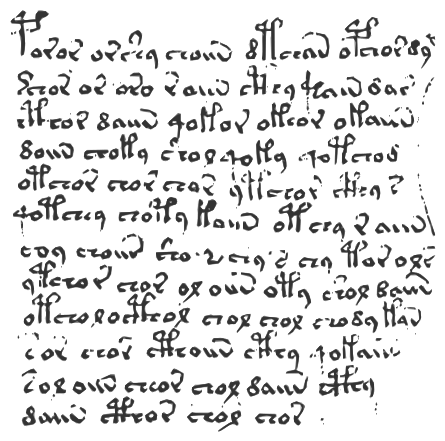

The Voynich manuscript is written in an unknown script.

Who was the Author?

Since the day the examinations on the book started, the first hypothesis considering its author were developed. In a letter to Athanasius Kircher, it was suggested that the author was the Franciscan friar and polymath Roger Bacon.[4] However, this is not the only theory. Many historians came across the name Edward Kelly, who was a self-styled alchemist and claimed to be able to invoke angels through a shewstone and had long conversations with them. The angels’ language was called Enochian, after Enoch, the Biblical father of Methuselah. Several people have suggested that Kelley could have fabricated the Voynich manuscript to swindle the emperor.

And What Does it Mean?

In concerns of the book’s languages, many hypothesis came up as well. It was suggested that the text could be a constructed language, others however prefer to believe that “the basis of the script was a very primitive form of synthetic universal language” (John Tiltman). Another theory is called the “letter-based cipher” theory. It suggest that the text contains a meaningful text in a European language, that was intentionally rendered obscure by mapping it to the Voynich manuscript “alphabet” through a cipher of some sort, an algorithm that operated on individual letters. This has been the working hypothesis for most twentieth-century deciphering attempts, including an informal team of NSA cryptographers. Further theories suggest that the text is made of a little-known natural language or that it contains a certain code to be looked up in a codebook.

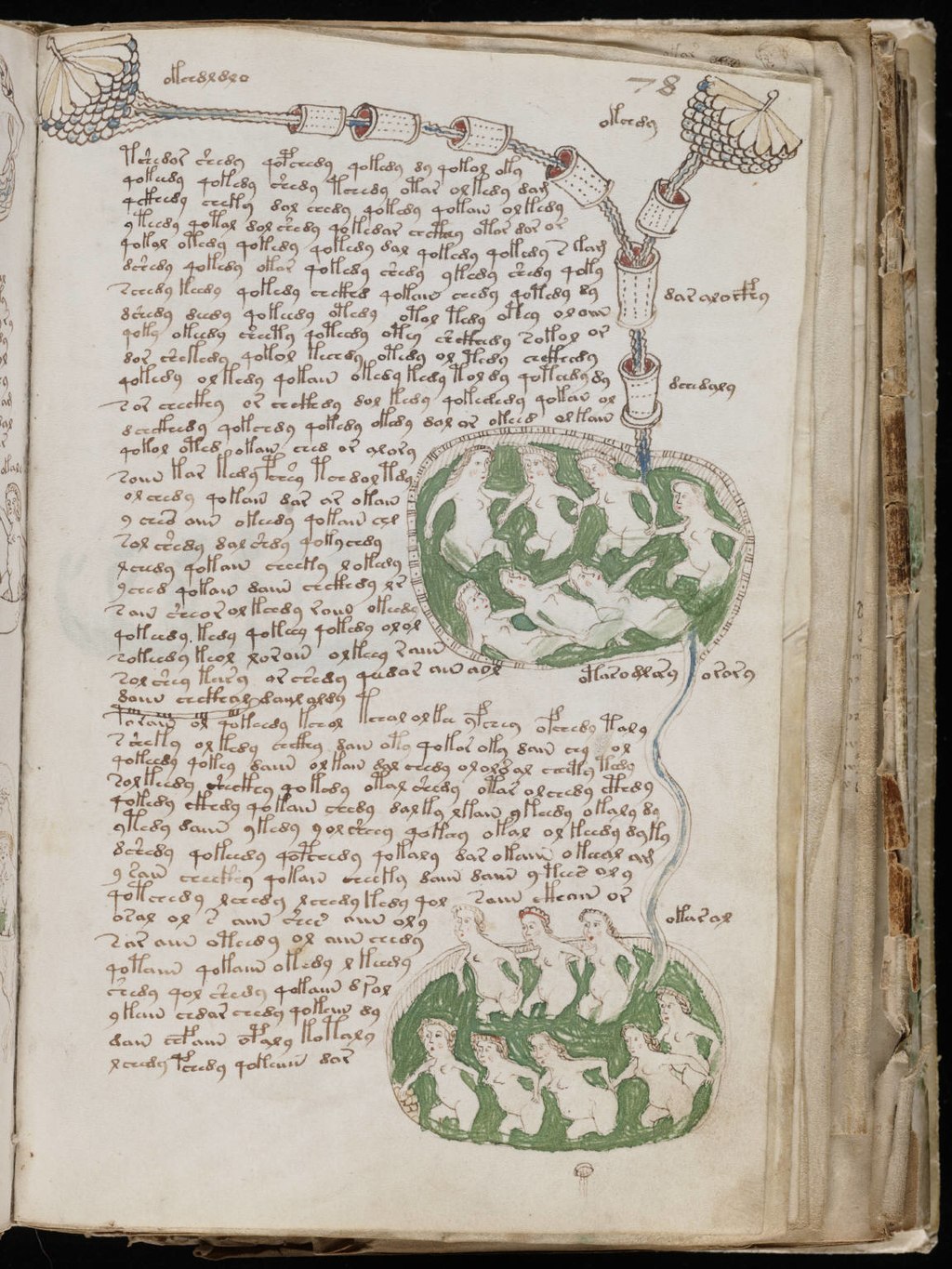

Another page from the mysterious Voynich manuscript from the so-called anatomical section

Content Analysis

The text of the manuscript contains approx. 35,000 “words”. These words have phonotactic characteristics similar to those of a natural language, i.e.,

- a subset of characters can be identified from which one or more characters appear in each word (analogous to the vowels), and

- some combinations of characters never appear.

The statistical analysis of the text reveals further similarities with natural languages:

- the word frequencies obey Zipf’s law,

- the word entropy equals with approx. 10 Shannon/word that of Latin or English, and

- some words appear only on certain pages or in certain sections, others appear everywhere in the text. In particular:

- the “labels” of the illustrations have very few repetitions, and

- in the “herbal section” the first word of each page only appears on this page (perhaps the name of the plant in question).

However, other peculiarities of the Voynich text are nowhere to be found in European languages. For example, there are hardly any words with more than ten, but also hardly any with less than three characters. Furthermore, there seem to be initial and final letter forms, i.e. special forms of characters at the beginning and end of words, as they are common in Semitic languages. And finally, immediate repetitions of the same word or smaller variants appear with unusual frequency.

Further Theories

This theory holds that the text of the Voynich manuscript is mostly meaningless, but contains meaningful information hidden in inconspicuous details – e.g., the second letter of every word, or the number of letters in each line. This technique, called steganography, is very old and was described by Johannes Trithemius in 1499. Though the plain text was speculated to have been extracted by a Cardan grille (an overlay with cut-outs for the meaningful text) of some sort, this seems somewhat unlikely because the words and letters are not arranged on anything like a regular grid. Still, steganographic claims are hard to prove or disprove, since stegotexts can be arbitrarily hard to find. It has been suggested that the meaningful text could be encoded in the length or shape of certain pen strokes. There are indeed examples of steganography from about that time that use letter shape (italic vs. upright) to hide information. However, when examined at high magnification, the Voynich manuscript pen strokes seem quite natural, and substantially affected by the uneven surface of the vellum.

Unfortunately of all the theories, nothing was completely proven and the mystery of the manuscript had quite a cultural impact. Several books, and papers were written about the book itself and also fiction works were published. This includes Russel Blake’s “Voynich Cypher“.

The Voynich Manuscript with Lisa Fagin Davis, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Unread: The Mystery of the Voynich Manuscript

- [2] The Voynich Manuscript at the Internet Archive

- [3] The Voynich Manuscript – The most mysterious manuscripts in the world

- [4] Athanasius Kircher – A Man in Search of Universal Knowledge, SciHi Blog

- [5] The Voynich manuscript at Wikidata

- [6] The Mystery of the Voynich Manuscript” – Scientific American – June 21, 2004

- [7] The Voynich Manuscript with Lisa Fagin Davis, Lisa Fagin Davis ’93 PhD, executive director of the Medieval Society of America and visiting professor of paleography at Yale, introduces the Voynich Manuscript (Beinecke Library MS 408) to the students in her Latin Paleography class at Yale, Beinecke Library at Yale @ youtube

- [8] D’Imperio, M.E. (1978). The Voynich Manuscript: An Elegant Enigma. National Security Agency.

- [9] Tiltman, John H. (Summer 1967). “The Voynich manuscript: The most mysterious manuscript in the world” (PDF). NSA Technical Journal. National Security Agency. XII (3).

- [10] Timeline of undeciphered historical codes or manuscripts, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Good day!

My name is Nikolai.

To a question about the key to the Voynich manuscript.

Today, I have to add on this matter following.

The manuscript was written no letters, and signs for the letters of the alphabet of one of the ancient languages. Moreover, in the text there are 2 more levels of encryption to virtually eliminate the possibility of computer-assisted translation, even after replacing the signs letters.

I pick up the key by which the first section I was able to read the following words: hemp, hemp clothing; food, food (sheet of 20 numbering on the Internet); cleaned (intestines), knowledge may wish to drink a sugary drink (nectar), maturation (maturity), to consider, to think (sheet 107); drink; six; flourishing; growing; rich; peas; sweet drink nectar and others. It is only a short word, mark 2-3. To translate words consisting of more than 2.3 characters is necessary to know this ancient language.

If you are interested, I am ready to send more detailed information, including scans of pages indicating the translated words.

Sincerely, Nicholas.

a_nikolaj@list.ru