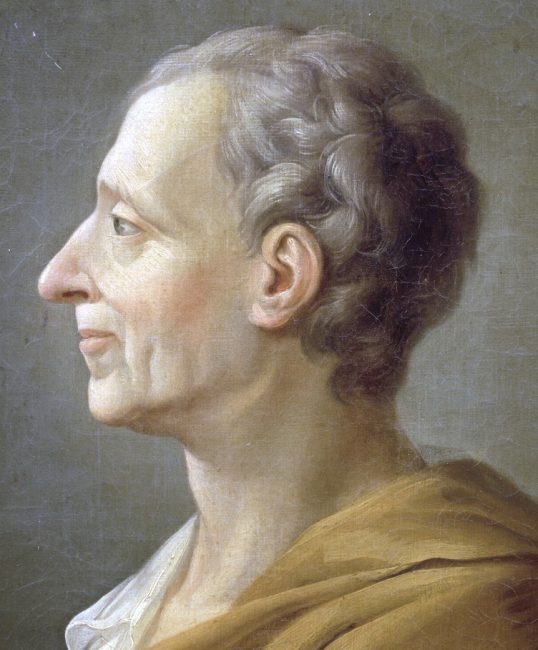

Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (1689 – 1755)

On January 18, 1698, French philosopher and political thinker Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu, generally only referred to as Montesquieu, was baptized. He is best known for his articulation of the theory of separation of powers, which is taken for granted in modern discussions of government and implemented in many constitutions throughout the world.

“If I knew of something that could serve my nation but would ruin another, I would not propose it to my prince, for I am first a man and only then a Frenchman…because I am necessarily a man, and only accidentally am I French.”

— Pensées et Fragments Inédits de Montesquieu (1899)

Montesquieu’s Youth and Education

Montesquieu was born on the country estate of La Brède, near Bordeaux, France, the son of Jacques de Secondat (1654-1713) and Marie-Françoise de Pesnel (1665-1696) in a family of high nobility, the so-called “noblesse parlementaire”. Even though, Montesquieu’s real date of birth is unknown, the offspring of the wealthy noble family was baptized on January 18, 1698 which is now referred to as his birthday. At the age of seven, Montesquieu lost his mother. From 1700 to 1705, as a boarding school student, he attended the College of Oratorian Monks in Juilly, not far from Paris, known for the critical spirit that prevailed there. He acquired a profound knowledge of Latin, mathematics and history and wrote a historical drama of which a fragment has survived. From 1705 to 1708 he studied law in Bordeaux. After graduating and being admitted as a lawyer, he was given the Baron title by the head of the family, his father’s eldest brother without children, and went to Paris for legal and other training, as he was also to inherit the office of president of the court, which had passed from grandfather to uncle. In Paris, he found a connection with intellectuals and began to write down thoughts and reflections of various kinds in a kind of diary.

On National Debts and Religious Politics

When his father died in 1713, he returned to Château de La Brède. In 1714 he received, certainly through his uncle, the office of a judicial council (conseiller) at the parliament of Bordeaux. But law was not the only scientific field he was interested in. Thus, after the death of Louis XIV (September 1715), he wrote a memorandum on economic policy on the national debt (Mémoire sur les dettes de l’État) addressed to Philip of Orléans, who ruled as regent for Louis XV until he should become of age. In 1716, he was admitted to the Académie de Bordeaux, one of the loosely organized circles that brought together scholars, literary figures and other people interested in intellectuals in larger cities. Here he gave lectures and wrote smaller works, e.g. a Treatise on the Religious Politics of the Romans, in which he tries to prove that religions are a useful instrument for moralizing the subjects of a state.

Literary Success

In 1721, Montesqieu became famous through a novel of letters which he had begun in 1717 and which was soon forbidden by censorship after its anonymous appearance in Amsterdam: the Lettres persanes (Persian Letters). The content of the work, which today is regarded as a key text of the Enlightenment, is the fictitious correspondence of two fictitious Persians who travelled Europe from 1711 to 1720 and exchanged letters with those who remained at home. Montesquieu deals in this writing with various topics such as religion, priesthood, slavery, polygamy, discrimination of women, etc. in the sense of the Enlightenment. In addition, a Romanesque storyline is woven into the Lettres around the harem ladies who remained at home, which was not entirely uninvolved in the success of the book.In 1725 he again achieved a considerable book success with the rococo-like-galant pastoral little novel Le Temple de Gnide, which he allegedly had found and translated in an older Greek manuscript.

“Not to be loved is a misfortune, but it is an insult to be loved no longer.”, Montesquieu, Lettres Persanes (Persian Letters, 1721)

![The title page of volume 1 of Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (1748) De l'Esprit des loix ou du rapport que les Loix doivent avoir avec la Constitution de chaque Gouvernement, les Moeurs, le Climat, la Religion, le Commerce, &c : à quoi l'Auteur a ajouté Des recherches nouvelles sur les Loix Romaines touchant les Successions, sur les Loix Françoises, & sur les Loix Féodales [The Spirit of the Laws, or the rapport that the Laws should have with the Constitution of each Government, the Customs, the Climate, the Religion, the Commerce, &c: to which the Author has added new research on the Roman Laws concerning Succession, on French Laws, and on the Feudal Laws], Geneva: Barrillot & Fils](http://scihi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Montesquieu_De_lEsprit_des_loix_1st_ed_1748_vol_1_title_page.jpeg)

The title page of volume 1 of Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (1748) De l’Esprit des loix ou du rapport que les Loix doivent avoir avec la Constitution de chaque Gouvernement, les Moeurs, le Climat, la Religion, le Commerce, Geneva: Barrillot & Fils

The Spirit of the Laws

Montesquieu began turning his back to his judicial office and began dedicating his life to the ‘Académie française‘, one of the institutes with the most prestige in France, a place for intellectuals in various fields. He also began travelling through Europe until 1731. When Montesquieu finally settled in is home town La Brède, he began writing an publishing his most influential works, like the ‘De l’esprit des lois‘ (The Spirit of the Laws) from 1748 which took about 20 years of writing and thinking.

“One must give one power a ballast, so to speak, to put it in a position to resist another.”

— Montesqieu, The Spirit of the Laws (1748) Book V, Chapter 14.

‘De l’esprit des lois‘ became Montesquieu’s most important work. In it, he mentions the decisive aspects determining the governmental and legal system of certain states, meaning that through these aspects a general spirit can be detected which was supposed to indicate a state’s spirit of laws. Also he takes a clear position against absolutism leading him to his famous theories on the ‘Separation of Powers‘. The mastermind, philosopher of the early Enlightenment, and the father of liberalism, John Locke, once set the first milestone for the theory. Montesquieu described in his work the separation of the legislature, the executive, and judiciary [4]. Right after being published, it was set on the ‘Index Librorum Prohibitorum‘. (the list of prohibited books) Montesquieu’s masterpiece contained liberal as well as conservative aspects, pledging for a parliament with at least two parties instead of a monarchy preventing despotism and anarchy. His first success earned Montesquieu through his work in the year of his passing, 1755. The Republic of Corsica solidified his ideas as part of their constitution in this year and the second and major breakthrough depicted the constitution of the United States of America, followed by every democratic state understanding the separation of power as the foundation of their constitutions.

Further Achievements

Montesquieu is credited as being among the progenitors, which include Herodotus and Tacitus, of anthropology, as being among the first to extend comparative methods of classification to the political forms in human societies. Another example of Montesquieu’s anthropological thinking, outlined in The Spirit of the Laws and hinted at in Persian Letters, is his meteorological climate theory, which holds that climate may substantially influence the nature of man and his society. By placing an emphasis on environmental influences as a material condition of life, Montesquieu prefigured modern anthropology’s concern with the impact of material conditions, such as available energy sources, organized production systems, and technologies, on the growth of complex socio-cultural systems.

Besides composing additional works on society and politics, Montesquieu traveled for a number of years through Europe including Austria and Hungary, spending a year in Italy and 18 months in England where he became a freemason, admitted to the Horn Tavern Lodge in Westminster, before resettling in France. Montesquieu was troubled by poor eyesight, and was completely blind by the time he died from a high fever in 1755.

2. The Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755), Alan Macfarlane, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Naturrecht, Gesetz und Gewaltenteilung (Auszüge aus ‘Vom Geist der Gesetze’) [In German]

- [2] Leben und Schaffen des Montesquieu [In German]

- [3] Montesquieu at Stanford

- [4] John Lock and the Social Contract, SciHi Blog, August 29, 2015.

- [5] Herodotus, the Father of History, SciHi Blog, November 25, 2015.

- [6] Montesquieu at Wikidata

- [7] Montesquieu Timeline at Wikidata

- [8] Works by or about Montesqieu at Wikisource

- [9] 2. The Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755), Alan Macfarlane, Cambridge University, 2001, Prof Alan Macfarlane – Ayabaya @ youtube

- [10] Saintsbury, George (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 775–778.

- [11] de Secondat, Charles, Baron de Montesquieu, “The Spirit of Laws” 2 vols. Originally published anonymously. 1748; Crowder, Wark, and Payne, 1777. Trans. Thomas Nugent (1750).

- [12] Works by or about Montesquieu at Internet Archive