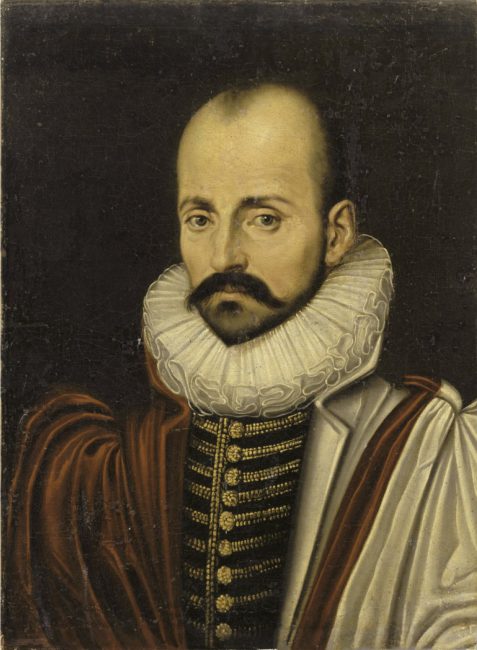

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592)

On February 28, 1533, French philosopher Michel de Montaigne was born. Montaigne was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance, known for popularizing the essay as a literary genre. His work is noted for its merging of casual anecdotes and autobiography with intellectual insight. His massive volume Essais contains some of the most influential essays ever written.

“We are, I know not how, double in ourselves, so that what we believe we disbelieve, and cannot rid ourselves of what we condemn.”

– Michel de Montagne, as quoted in [9]

Michel de Montaigne – Early Years

Montaigne was born Michel Eyquem at the Château de Montaigne as the eldest of four children of Pierre Eyquem, a Roman Catholic Frenchman who had accompanied King Francis I on his Italian campaign and who had come into contact with the ideas of the Renaissance and Humanism. The father held several high offices in the city of Bordeaux. Montaigne’s mother was Antoinette de Louppes de Villeneuve (1514-1603) from Toulouse. After his birth, Montaigne was given to a nurse living in simple conditions in the nearby hamlet of Papessus near Montpeyroux. When he returned to his family at about three years of age, his father hired a doctor from Germany called Horstanus as a tutor, who could speak neither French nor Gascognic and who spoke only Latin with the child. Since the parents also tried to do so and even the servants had to try, Latin almost became Montaigne’s mother tongue. From 1539 to 1546 Montaigne attended the Collège de Guyenne in Bordeaux, where he was sometimes feared by his teachers because he spoke Latin better than they did. Almost nothing is known about the years 1546 to 1554. Montaigne probably first completed propaedeutic studies at the Artist Faculty of Bordeaux, followed by studies in law.

Councillor of Justice and Political Work

“I want to be seen here in my simple, natural, ordinary fashion, without straining or artifice; for it is myself that I portray…I am myself the matter of my book.”

– Michel de Montagne, Essays

In 1554, at the age of twenty-one, Montaigne was appointed to the post of judicial councillor, conseiller at the tax court, Cour des aides, in Périgueux. That same year, he accompanied his father, who had just been elected mayor, to Paris for negotiations with the king. An uncle of Montaigne, Pierre Eyquem seigneur de Gaujac, gave him his seat of judge in Périgueux in 1556. When the tax court of Périgueux was dissolved in 1557, Montaigne was given a judicial council post at the Parlement of Bordeaux, the supreme court of the province of Guyenne. In Bordeaux, he was primarily responsible for the Chamber of Appeal, Chambre des Enquêtes. There he investigated and judged legal cases. As a judge on appeal, he did not pass judgement himself, but gave his written assessment to his fellow judges who were hearing the case. In addition, he also presided over civil proceedings. He travelled to Paris in 1559, 1560 and 1562 in his capacity as Councillor of Justice.

Commitment to Catholicism and first Writings

During his last stay in Paris, which was overshadowed by the beginning of the Huguenot wars with the massacre of Wassy, Montaigne, together with other judges of various French parliaments, solemnly made a commitment to Catholicism. On the death of his father, Pierre Eyquem de Montaigne, in 1568, he inherited the bulk of his property, according to the rules of the noble division of the estate. In 1569, he completed an annotated translation of the Theologia naturalis seu liber creaturarum (1434-1436) “Book of Creatures” by the Catalan theologian and physician Raimond Sebond, a native of Toulouse. He had begun it still at the request of his father. At the same time as this translation from Latin into French, Montaigne gave in Paris a collection of French and Latin poems by his friend La Boétie in print.

Enough lived for Others

“Wherever your life ends, it is all there. The advantage of living is not measured by length, but by use; some men have lived long, and lived little; attend to it while you are in it. It lies in your will, not in the number of years, for you to have lived enough.”

– Michel de Montagne, Essays

In 1571, at the age of thirty-eight, Montaigne resigned from his position as judge and retired to his castle. “Enough lived for others – let us at least live this last part of life for ourselves” is his own statement about this retreat. “Enough lived for others – let us at least live this last piece of life for ourselves” is his own statement on this retreat. With the role of the landed gentry, when the Montaigne saw himself clearly after his retreat into the private sphere, it was perfectly compatible with reading and literary dabbling. He did this with the help of a private library (about a thousand volumes), which was relatively large by the standards of the time and which had been bequeathed to him in large part by his friend La Boétie.

The Essays

“A man must be a little mad if he does not want to be even more stupid.”

– Michel de Montagne, Essays

He began to write down striking sentences from the works of classical, mostly Latin authors and to make them the starting point for his own reflections. He saw these reflections as attempts to get to the bottom of the nature of the human being and the problems of existence, especially death. He himself had to develop the appropriate form of representation for these “attempts” (French essais) in a tentative way, because only later, after him and thanks to him, the term essay became the name of a new literary genre. While writing, Montaigne describes his thoughts as if the page before him were his counterpart – just as he would tell his lost friend la Boétie. Changing himself over time, he also encounters the text in a new way when he reads it again. He then corrects, completes and rejects it from the new perspective. His thought process leads him to change himself in turn. “For him, the whole of humanity consists of nothing but moments governed by his own laws, and he reproduces his empathy with his own past.”

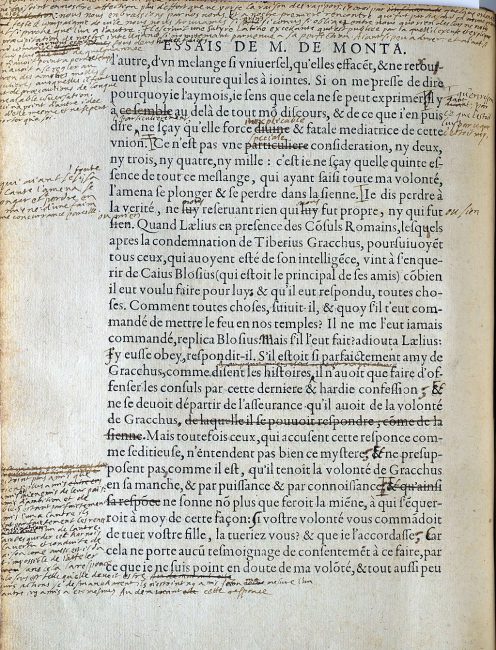

The Essais copy annotated by Montaigne, Bordeaux edition

It was written in the years from 1572 until his death in 1592, and in numerous sections he describes different objects of equally different rank; these range, for example, from confessional disputes to medicine and medical science to fundamental problems of human knowledge. Topics such as interpersonal coexistence, witch trials and superstition, but also riding and horses are treated side by side in kaleidoscopic diversity. Leitmotivic thoughts emerge only at second glance. The Essays change the style of the tractate that has predominated until now. Montaigne pursues an eclectic treatment of his themes. Inspired by ancient authors and philosophical schools, such as Lucretius and his De rerum natura, Cicero, the Epicureans, the Stoa and the Skeptics, he combined spontaneous, associative and volatile ideas into anecdotal texts.

St Bartholomew’s Night

“If it is not beautiful on the right, go left; if I am unable to mount my horse, I will stop… Did I forget to look at something? I turn back; that way I always find my way. I do not plan a line in advance, neither the straight nor the crooked one.”

– Michel de Montaigne, Essais, III, 9

Michel de Montaigne had probably combined his move into the private sphere with the hope of spending his days undisturbed by the warlike turmoil of the time. However, when the division in the country deepened after the massacres of the St. Bartholomew’s Night (August 22/23, 1572) and both sides again fought each other, he considered it his duty to join the royal army and thus the Catholic camp. In 1574, however, he also advocated a reconciliation of the denominations with a speech before the judges of the parliament in Bordeaux. After the peace treaty of 1575, which temporarily granted full civil rights to the Protestants, he had Henry of Navarre, the de facto ruler of much of western France, appoint him as his chamberlain.

Travels to Italy

As he had been suffering from renal colic since 1577 (whose strong effects on his condition, thinking and feeling he discussed in the Essais), Montaigne went on a trip to baths in 1580, despite the renewed outbreak of war in France, from which he hoped for relief[47] The trip took him via Paris, where he was received by King Henry III, to several French, Swiss and German baths. The journey presumably led along the postal routes of the time (see the map of the state in 1563) and also served as an educational journey. Montaigne described the journey in a diary, which he did not publish. The manuscript was not found until 1770 by Joseph Prunis in an old chest at Montaigne Castle, and it was printed in 1774.

Mayor of Bordeaux

From 1581 to 1585 Michel de Montaigne was appointed mayor of Bordeaux. In his office as mayor, Montaigne always tried to mediate between the Reformed and the Catholics, and in 1583 he negotiated with Henry of Navarre, who in 1584 became the closest candidate for the throne. Six weeks after the end of his second term as mayor, on 31 July 1585, the plague broke out in Bordeaux. In the period from June to December there were about fourteen thousand victims. After the end of his time as mayor in the late summer of 1585 and the temporary escape from the plague epidemic, he sat down again in his library in the castle tower to process new readings, experiences and insights in the Essais, which he greatly expanded and added a third volume.

Final Years

“Let us give Nature a chance; she knows her business better than we do”

– Michel de Montagne, Essays

When he left for Paris on 23 January 1588 to print the new version there, he was robbed on the way by noble highwaymen, but got the manuscript back from them. In the years that followed, he continued to revise and multiply the Essais. In 1590 he witnessed the marriage of his only daughter, who had reached adulthood, and in 1591 the birth of a granddaughter. Montaigne died suddenly during a mass in the château chapel on 13 September 1592, possibly suffering from the so-called “neck tan”, an old name for diphtheria.

Montaigne’s Epistemology

For Michel de Montaigne, sensual perception was a highly unreliable act, because people can suffer from false perceptions, illusions, hallucinations; one could not even be sure that one was not dreaming. The person who perceives the world with his senses hopes to gain knowledge from it. But he is subject to the danger of illusion, and the human senses are not sufficient to grasp the true essence of things. He considers it impossible to separate the appearance from the actual being, for this requires a criterion as an unmistakable sign of correctness. Montaigne uses the term apparence (appearance) to create a way out. Although man cannot recognize the essence of things, he is able to perceive them in their constantly changing appearances.

David Schaeffer on Montaigne and Happiness, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Works by or about Michel de Montaigne at Internet Archive

- [2] Works by Michel de Montaigne at LibriVox

- [3] Facsimile and HTML versions of the 10 Volume Essays of Montaigne at the Online Library of Liberty

- [4] Montaigne Studies at the University of Chicago

- [5] Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). . Collier’s New Encyclopedia. New York: P. F. Collier & Son Company.

- [6] Michel de Montagne, French writer and philosopher, at Britannica online

- [7] Michel de Montaigne at Wikidata

- [8] Timeline of Michel de Montagne, via Wikidata

- [9] David Schaeffer on Montaigne and Happiness,

- [10] The Complete Works of Michael de Montaigne (1877) edited by William Carew Hazlitt, p. 289