Mary Anning with her dog, Tray, painted before 1842

On May 21, 1799, British fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist Mary Anning was born. She became known around the world for important finds she made in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Channel at Lyme Regis in the county of Dorset in Southwest England. Her work contributed to fundamental changes in scientific thinking about prehistoric life and the history of the Earth.

“She sells sea-shells on the sea-shore,

The shells she sells are sea-shells, I’m sure

For if she sells sea-shells on the sea-shore

Then I’m sure she sells sea-shore shells.”

— Tongue-twister by Terry Sullivan (1908), suggested as inspired by Mary Anning

Mary Anning – Becoming a Fossil Hunter

Mary Anning was born in Dorset, England and her father, a carpenter, had often taken Mary and her brother Joseph to his fossil-hunting trips from which he found pieces to sell to tourists. Mary was one of ten children, of whom only she and her brother Joseph survived childhood. When her father passed away, Mary continued the fossil-finding trips near the sea. Her fossil hunt turned out especially fruitful when the tide was low, but still, collecting fossils remained a risky business. After a while, Mary Anning’s family established a good reputation as fossil hunters and it supported the family financially. Collecting fossils had become fashionable in the late 18th and early 19th century. Initially no more than a hobby, the importance of fossils for geology and biology was gradually recognised. If Mary Anning began collecting merely to earn a living, she soon had connections with the geologists and biologists of her time. Around 1817, the family met Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Birch, a fossil collector who later on became the supporter of the family. He attributed the major fossil discoveries to Mary Anning’s family and even sold some of his most valuable collections of fossils to those who would buy them to help the family. To this day, it is hard to trace, which of the found fossils can be really attributed to Mary Anning because museums usually credited the individuals who donated the fossils to them.

The Ichthyosaurus

For instance, she is credited with the discovery of the Ichthyosaurus fossils, but indeed it is believed that her brother had found the skull of the beast and she had contributed by finding the rest of it. It was her brother, who had discovered a skull that looked like that of a large crocodile. The rest of the skeleton could not be found at first, until Mary found the rest of the body after a storm that tore away parts of the cliff. This was the first complete skeleton of an ichthyosaurus to be found at that time. Parts of skeletons had been found before and the species had been described in 1699 using fragments discovered in Wales. However, the important discovery of a complete skeleton was included in the Transactions of the Royal Society. Mary Anning was twelve years old at this time.

A Visit by Louis Agassiz

Unfortunately for Mary Anning, women were not officially allowed to attend the university and despite the fact that she had made so many wonderful discoveries, she was often not properly credited in the publications. However, this did not apply to everyone. The famous Swiss paleontologist Louis Agassiz visited Lyme Regis in 1834 and worked with Anning to obtain and study fish fossils found in the region.[4] He was so impressed by her and her friend Elizabeth Philpot that he wrote in his journal: “Miss Philpot and Mary Anning have been able to show me with utter certainty which are the icthyodorulites dorsal fins of sharks that correspond to different types.” He thanked both of them for their help in his book, Studies of Fossil Fish.

![Drawing from an 1814 paper[21] by Everard Home showing the Ichthyosaurus platyodon skull found by Joseph Anning in 1811](http://scihi.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/AnningIchthyosaurSkull-650x250.jpg)

Drawing from an 1814 paper[21] by Everard Home showing the Ichthyosaurus platyodon skull found by Joseph Anning in 1811

Further Discoveries

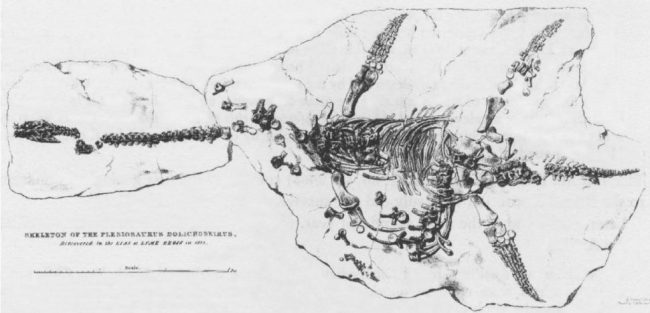

Her next major fossil find was that of a Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus in 1821, the first to be found of this genus, which has not been surpassed in quality until today. It was scientifically described by the paleontologist and geologist William Daniel Conybeare. In 1828, the third major find was a pterosaur, described by William Buckland in 1829 as Pterodactylus macronyx (Richard Owen later placed the species in the new genus Dimorphodon), the first find outside Germany (Gideon Mantell considered his pterosaur fossils, described in 1827, to be the remains of a bird). With these three important finds Mary Anning found her place in paleontology. Her achievement consisted not only in her extraordinary talent for finding fossils, but also in the care and patience with which she excavated them. She worked on the excavation of the plesiosaurus for ten years without outside assistance, using the simplest of tools. Moreover, she – who never had any scientific training of any kind – was both able to draw her finds competently and to describe them accurately.

Lithograph of Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus skeleton found by Mary Anning in 1823, published in 1824 transactions of the Geological Society of London

Charles Lyell and Gideon Mantell

Another leading British geologist, Roderick Murchison, did some of his first field work in southwest England, including Lyme, accompanied by his wife, Charlotte. Murchison wrote that they decided Charlotte should stay behind in Lyme for a few weeks to “become a good practical fossilist, by working with the celebrated Mary Anning of that place…“. Charlotte and Anning became lifelong friends and correspondents. Gideon Mantell, discoverer of the dinosaur Iguanodon, also visited her at her shop.[5] Anning’s correspondents included Charles Lyell, who wrote to her to ask her opinion on how the sea was affecting the coastal cliffs around Lyme, as well as Adam Sedgwick—one of her earliest customers—who taught geology at the University of Cambridge and who numbered Charles Darwin among his students.[6]

Death and Legacy

Mary Anning searched her whole life for fossils and with her finds she contributed significantly to the development of early paleontology. In her late thirties she received an annual pension from the British Association for the Advancement of Science in gratitude for her achievements. In 1847, Mary Anning died from breast cancer at the age of only 47. Charles Dickens wrote an article about her life in February 1865 in his literary magazine ‘All the Year Round‘ that emphasised the difficulties she had overcome, especially the scepticism of her fellow townspeople. He ended the article with: “The carpenter’s daughter has won a name for herself, and has deserved to win it.” Mary Anning’s finds were important evidence of the extinction of animal species. Until her time, it was generally believed that animal species did not become extinct; every strange find was explained as an animal still living somewhere in an undiscovered part of the world. The bizarre nature of the fossils Anning found undermined this argument and supported Georges Cuvier’s controversial thesis that they were extinct species. This paved the way for the understanding of life in earlier geological ages. The coast where Mary made her finds – commonly called Jurassic Coast – is now one of the most famous sites for dinosaur fossils in the world. The oldest layers of the coast date back to the Triassic period and can be dated to an age of about 250 million years.

Mary Anning – Princess of Paleontology – Extra History, [15]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Mary Anning at UC Berkeley

- [2] Mary Anning at Famous Scientists

- [3] Mary Anning Biography

- [4] Louis Agassiz and the Ice Ages, SciHi Blog

- [5] Gideon Mantell and the Iguanodon, SciHi Blog

- [6] Charles Lyell and the Principles of Geology, SciHi Blog

- [7] Mary Anning at Wikidata

- [8] Extra History: Mary Anning – Princess of Paleontology

- [9] Bill Bryson: A short History of nearly Everything. Broadway Books, New York 2003.

- [10] “Episode 10: Mary Anning” (podcast). Babes of Science.

- [11] Torrens, Hugh (1995), “Mary Anning (1799–1847) of Lyme; ‘The Greatest Fossilist the World Ever Knew‘“, The British Journal for the History of Science, 25 (3): 257–284.

- [12] Conybeare, William (1824), “On the Discovery of an almost perfect Skeleton of the Plesiosaurus”, Transactions of the Geological Society of London, Geological Society of London, S2-1 (2): 381–389

- [13] “Mary Anning (1799–1847)”. UC Berkeley Museum of Paleontology.

- [14] Pepper, Fiona; Street, Julie. “Mary Anning inspired ‘she sells sea shells’ — but she was actually a legendary fossil hunter”. Late Night Live. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (article and podcast)

- [15] Mary Anning – Princess of Paleontology – Extra History, Extra Credits @ youtube

- [16] Timeline of Women Paleontologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata