Marie Lafarge (1816 – 1852)

On September 19, 1840, Marie-Fortunée Fafarge was convicted of murdering her husband by arsenic poisoning. Her case has become notable because she was the first person convicted largely on direct forensic toxicological evidence.

Marie Lafarge – Background

Marie Lafarge grew up with her maternal aunt and was sent to only the best schools throughout her youth. Wealth has always been an important issue of her life. Coming from a rather poor family, she mainly spent time with rich peers. Her friends soon started to marry wealthy noblemen while Marie Lafarge found no partner for life in the ‘right’ circles due to her financial situation. When she turned 23 and still found nobody, Lafarge became quite jealous and was soon connected with Charles Lafarge through contacts of her uncle. He came from a prominent family and convinced Marie along with her family to be a wealthy iron master but unfortunately lost almost all of his property and money during the French Revolution. Even though Marie was not quite impressed by her future husband, she liked his wealth and soon agreed to marry him.

The Crime

On August 13, they arrived at their new home and Marie noticed the fraud. The situation made her mad, the house was full of rats, her family-in-law did not trust her and her husband was in deep dept. During the winter time, Charles Lafarge became suddenly ill and nobody was suspicious that his wife asked the doctor for an arsenic prescription, since she wanted to kill the many rats in the house. Charles did not recover and was diagnosed with cholera. Unfortunately for Marie, another family member witnessed her stirring white powder into her husband’s food and got suspicious. Right before Charles Lafarge died, his wife was convicted of the crime.

Toxicological Examination

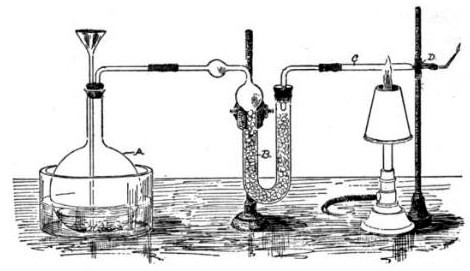

The police was informed and a post-mortem examination was to be performed. The Marsh test was back then a new method in order to detect arsenic in a dead person’s body. However, the test was not used in this case. The investigators only observed the insides of Lafarge’s stomach and indeed tested it positive on the poison. The Marsh test was actually invented in 1836 by a Scottish chemist named James Marsh, who worked at the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich. Called upon to help solve a murder nearby, he tried to detect arsenic using the old methods. While he was successful, the sample had decomposed and did not convince the jury of the defendant’s guilt. Frustrated at this turn of events, Marsh developed a glass apparatus not only to detect minute traces of arsenic, but also to measure its quantity. The sample is mixed with arsenic-free zinc and sulphuric acid, any arsenic present causing the production of arsine gas and hydrogen. The gas is then led through a tube where it is heated strongly, decomposing into hydrogen and arsenic vapor. When the arsenic vapor impinges on a cold surface, a mirror-like deposit of arsenic forms.

Marsh Test [7]

Gaining Popular Interest

Her case gained lots of social interest and numerous people came from all over the continent to watch the trial. Her defense lawyer knew about the Marsh test and insisted it to be performed since it was the most reliable method. When the investigators got back the results showed no evidence of arsenic. When further testing was performed, again no poison was found. The prosecutor then insisted that the food, Marie Lafarge gave her husband had to be examined and it was tested positive. It was later found that the first tests were performed incorrectly. Marie Lafarge was to serve life imprisonment combined with hard labor. King Louis-Philippe, however, commuted her sentence to life without hard labor.

Guilty or Innocent?

By then, the affair had polarized French society. The case turned out to be highly controversial and divided the country into two parties, believing Marie Lafarge to be guilty or innocent. The press however demanded to broaden the field of forensic toxicology with success. The knowledge grew and a new field of research evolved to help investigations in the future. While imprisoned, Marie Lafarge wrote her Mémoires, which was published in 1841. At last, in June 1852, stricken with tuberculosis, she was released by Napoleon III. She settled in Ussat in the département of Ariège and died on 7 November the same year, protesting her innocence to the last.

Early forensics and crime-solving chemists – Deborah Blum, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Lafarge Case at Visible Proofs

- [2] Lafarge at Murderpedia

- [3] The Art of Forensic Toxicology

- [4] Eugene Vidocq – The Father of Criminology, SciHi Blog

- [5] The Still Unsolved Case of Jack the Ripper , SciHi Blog

- [6] Marie Lafarge at Wikidata

- [7] – page 397 of An Introduction to Chemical Pharmacology (Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son & Co.)

- [8] Early forensics and crime-solving chemists – Deborah Blum, 2013, TED-Ed @ youtube

- [9] Marsh J. (1837). “Arsenic; nouveau procédé pour le découvrir dans les substances auxquelles il est mêlé”. Journal de Pharmacie. 23: 553–562.

- [10] Harkins, W. D. (1910). “The Marsh test and Excess Potential (First Paper.1) The Quantitative Determination of Arsenic”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 32 (4): 518–530.

- [11] Lafarge, M. (1867). Mémoires de madame Lafarge, née Marie Cappelle, écrits par elle-même. Paris: Lévy frères.

- [12] Timeline of Poisoners, via Wikidata and DBpedia