Frederick sends out the boy to see whether the ravens still fly Frederick I ‘Barbarossa’ in a typical folk tale

On June 10, 1190, Frederick I, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and better known as Frederick Barbarossa passed away. He died by drowning in the river Saleph during the Third Crusade. He got the name Barbarossa from the northern Italian cities he attempted to rule: Barbarossa means “red beard” in Italian; in German, he was known as ‘Kaiser Rotbart‘, which has the same meaning. There was a time, when every German school kid knew the history of ‘Kaiser Rotbart‘, who had become a mythological figure, resting in his quiet rock tomb in the Kyffhäuser mountain. According to folk lore, the ravens will watch over his tomb and keep on circling over the Kyffhäuser, until he will awake from his thousand years sleep again to start his comeback. A legend, which was fostered by the literates of the romantic movement in 19th century Germany. But, there is also a historical figure behind the legend.

“Let no emperor be subject to anyone but God and justice.”

– Frederick I

Frederick’s Youth

Frederick was born in 1122. Frederick’s father was from the Hohenstaufen family, and his mother was from the Welf family, the two most powerful families in Germany. At age 25 he became Duke of Swabia in 1147, and shortly afterwards made his first trip to the East, accompanied by his uncle, the German king Conrad III, on the Second Crusade. The expedition proved to be a disaster, but Frederick distinguished himself and won the complete confidence of the king. When Conrad died in February 1152, only Frederick and the prince-bishop of Bamberg were at his deathbed. Both asserted afterwards that Conrad had, in full possession of his mental powers, handed the royal insignia to Frederick and indicated that Frederick, rather than Conrad’s own six-year-old son succeed him as king.

To be Crowned King of the Romans

On 4 March 1152 the kingdom’s princely electors in Frankfurt designated Frederick as the next German king, to be crowned King of the Romans at Aachen only several days later. The status of the German empire by that time was in disarray, its power waning under the weight of the Investiture controversy with Henry IV.[3] The German monarchy was largely a nominal title with no real power. When Frederick I of Hohenstaufen was chosen as king in 1152, royal power had been in effective abeyance for over twenty-five years. The only real claim to wealth lay in the rich cities of northern Italy, which were still within the nominal control of the German king.

The Revolt of Lombardy

In 1158 Milan, the chief city of Lombardy, revolted and over the Alps came an army of a hundred thousand German soldiers, with Frederick Barbarossa at their head. After a long siege the city surrendered, but soon it revolted again. The emperor besieged it once more and once more it surrendered. Its fortifications were destroyed and many of its buildings ruined. But even then the spirit of the Lombards was not broken. Milan and the other cities of Lombardy united in a league and defied the emperor. He called upon the German dukes to bring their men to his aid. All responded except Henry the Lion, duke of Saxony, Frederick’s cousin. Frederick is said to have knelt and implored Henry to do his duty, but in vain. Frederick’s campaign against the Lombards failed and his army was completely defeated.

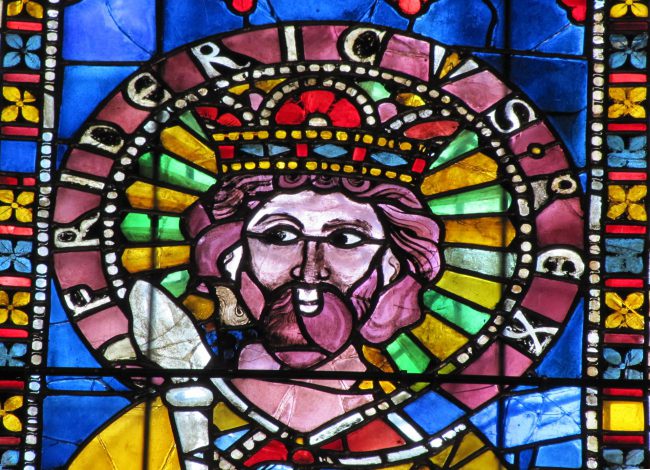

13th-century stained glass image of Frederick I, Strasbourg Cathedral

In Troubles with the Pope

On 9 June 1156 at Würzburg, Frederick married Beatrice of Burgundy, thus adding to his possessions the sizeable realm of the County of Burgundy. He also declared himself the sole Augustus of the Roman world. In June 1158, Barbarossa prepared a large expedition to Italy. In the years since he was crowned, a growing rift had opened between the emperor and the pope. While Barbarossa believed that the pope should be subject to the emperor, Pope Adrian claimed the opposite. Marching into Italy, Barbarossa sought to reassert his imperial sovereignty. Sweeping through the northern part of the country, he conquered city after city and occupied Milan on September 7, 1158. As tensions grew, Adrian considered excommunicating the emperor, however he died before taking any action. In September 1159, Pope Alexander III was elected and immediately moved to claim papal supremacy over the empire. In response to Alexander’s actions and his excommunication, Barbarossa began supporting a series of antipopes.

A Decisive Victory and a New Crusade

In 1166, Barbarossa attacked towards Rome at won a decisive victory at the Battle of Monte Porzio. His success proved short-lived as disease ravaged his army and he was forced to retreat back to Germany. Remaining in his realm for six years, he worked to improve diplomatic relations with England, France, and the Byzantine Empire. Though Barbarossa had reconciled with the pope, he continued to take actions to strengthen his position in Italy. In 1183, he signed a treaty with the Lombard League, separating them from the pope. After the Christians had held Jerusalem for eighty-eight years, it was recaptured by the Moslems under the lead of the famous Saladin , in the year 1187. There was much excitement in Christendom, and the Pope proclaimed another Crusade. Frederick immediately raised an army of Crusaders in the German Empire and with one hundred and fifty thousand men started for Palestine. He marched into Asia Minor, attacked the Moslem forces, and defeated them in two great battles.

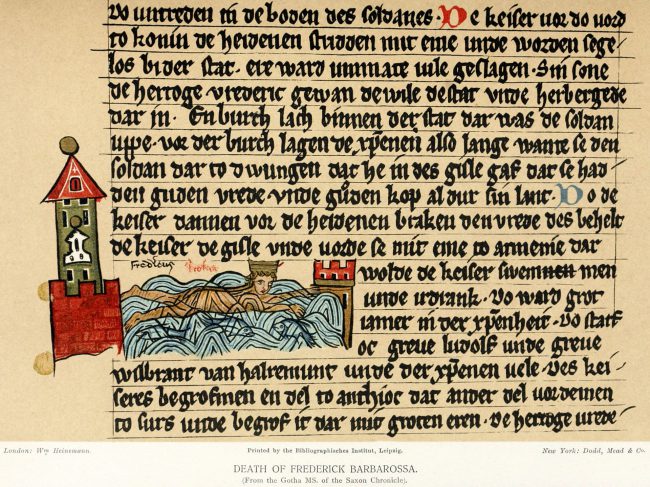

At the River Saleph

On 10 June 1190, Emperor Frederick’s career was put to an end when he drowned in the Saleph river. He had decided to walk his horse through the river instead of crossing the bridge that had been too crowded with troops. The current was too strong for the horse to handle, and his suit armour was too heavy for him to swim in: both were swept away and drowned. Some historians believe he may have had a heart attack that complicated matters. Some of Frederick’s men put him in a barrel of vinegar to preserve his body.

Barbarossa drowns in the Saleph, from the Gotha Manuscript of the Saxon World Chronicle

But he’s not really dead, is he? – The Legend

In the Empire the dead emperor was long mourned and for many years the peasants believed that Frederick was not really dead, but was asleep in a cave in the Kyffhäuser mountain in Germany, with his gallant knights around him. He was supposed to be sitting in his chair of state, with the crown upon his head, his eyes half-closed in slumber, his beard as white as snow and so long that it reached the ground. “When the ravens cease to fly round the mountain,” said the legend, “Barbarossa shall awake and restore Germany to its ancient greatness.” Even today you will find references to the legendary emperor in literature. Umberto Eco made Frederick Barbarossa to one of his protagonists in his historical novel Baudolino.[4] There, you can learn about Barbarossas constant quarrel with the Northern Italian city states, his departure for the Third Crusade and his death by drowning in the river Saleph.

John Green, The Crusades – Pilgrimage or Holy War?: Crash Course World History #15, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Famous People of the Middle Ages – Frederick Barbarossa

- [2] Frederick I at about.com Military History

- [3] Henry IV and his Walk to Canossa, SciHi Blog

- [4] Umberto Eco and the Name of the Rose, SciHi Blog

- [5] Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor, at Wikidata

- [6] Books about Frederick I at Wikisource

- [7] John Green, The Crusades – Pilgrimage or Holy War?: Crash Course World History #15, 2012, CrashCourse @ youtube

- [8] Holder-Egger, Oswald, ed. (1892). “Gesta Federici I. Imperatoris in Expeditione Sacra”. Gesta Federici I. Imperatoris in Lombardia. Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Vol. Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum, 27. Hanover. pp. 74–98.

- [9] Loud, Graham, ed. (2010). The Crusade of Frederick Barbarossa: The History of the Expedition of the Emperor Frederick and Related Texts. Ashgate.

- [10] Timeline of Holy Roman Emperors and Empresses, via DBpedia and Wikidata