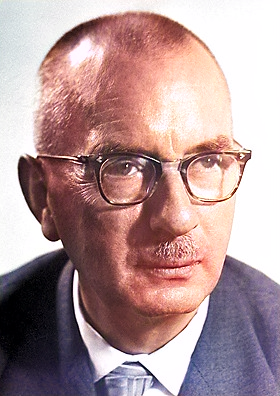

Karl Waldemar Ziegler (November 26, 1898 – August 12, 1973)

On November 26, 1898, German chemist and Nobel laureate Karl Ziegler was born. Ziegler won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1963, with Giulio Natta, for work on polymers. He is also known for his work involving free-radicals, many-membered rings, and organometallic compounds, as well as the development of Ziegler–Natta catalyst.

Youth and Education

Karl Ziegler was born in Helsa near Kassel, Germany and was the second son of Karl Ziegler, a Lutheran minister, and Luise Rall Ziegler. He attended Kassel-Bettenhausen in elementary school. An introductory physics textbook first sparked Ziegler’s interest in science. It drove him to perform experiments in his home and to read extensively beyond his high school curriculum. His extra study and experimentation enabled him to receive an award for most outstanding student in his final year at high school in Kassel, Germany. He studied at the University of Marburg and was able to omit his first two semesters of study due to his extensive background knowledge. His studies were interrupted however, as during 1918 he was deployed to the front as a soldier to serve in World War I.

Academic Career and First Research Endeavours

Ziegler received his Ph.D. in 1920, studying under Karl von Auwers with a dissertation on “Studies on semibenzole and related links”“. Soon after, he briefly lectured at the University of Marburg and the University of Frankfurt. In 1926 he became a professor at the University of Heidelberg where he spent the next ten years researching new advances in organic chemistry. He investigated the stability of radicals on trivalent carbons leading him to study organometallic compounds and their application in his research. He also worked on the syntheses of multi-membered ring systems. In 1933 Zielger published his first major work on large ring systems, “Vielgliedrige Ringsysteme” which presented the fundamentals for the Ruggli-Ziegler dilution principle.

In 1936 he became Professor and Director of the Chemical Institute (Chemisches Institut) at the University of Halle/Saale and was also a visiting lecturer at the University of Chicago. From 1943 until 1969, Ziegler was the Director of the Max Planck Institute for Coal Research (Max-Planck-Institut fur Kohlenforschung) formerly known as the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute for Coal Research (Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut fur Kohlenforschung) in Mülheim an der Ruhr. Karl Ziegler was credited for much of the post war resurrection of chemical research in Germany and helped in founding the German Chemical Society (Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker) in 1949.

Ziegler’s Research – from the fundamental to the most practical

Throughout his life, Ziegler was a zealous advocate for the necessary indivisibility of all kinds of research. Because of this, his scientific achievements range from the fundamental to the most practical, and his research spans a wide range of topics within the field of chemistry. As a young professor, Ziegler posed the question: what factors contribute to the dissociation of carbon-carbon bonds in substituted ethane derivatives? This question was to lead Ziegler on to a study of free radicals, organometallics, ring compounds, and, finally, polymerization processes.

Between 1952 and 1953, Ziegler and Hans-Georg Gellert, one of his former students from Halle, found that in the polymerization reaction organolithium compounds, except for lithium aluminum hydride, irreversibly decomposed into lithium hydride and an alkyl. To establish whether lithium or aluminum was the more active metal, Gellert tested organoaluminum compounds. Triethylaluminum added several ethylene molecules end-to-end, but the carbon atom chains differed in length because a competing chain-ending reaction stopped the polymerization at different carbon atoms in the chain. Ziegler’s research associate, Heinz Martin, and two graduate students, Erhard Holzkamp and Heinz Breil, discovered the cause of the chain-ending reaction. Holzkamp reacted isopropylaluminum and ethylene in a stainless-steel autoclave at 100 to 200 atmospheres and 100 °C. They expected to produce an odd-numbered alkene but instead obtained exclusively 1-butene.

Further investigation by Ziegler and Holzkamp revealed that acidic cleaning of the autoclave wall released traces of nickel, which had stopped the polymerization reaction. Holzkamp confirmed this conclusion by deliberately adding nickel salts to the triethylaluminum-ethylene mixture in a glass reactor.[2] Holzkamp reacted chromium and produced polyethylene along with butene and other alkenes. Breil tested several closely related transition elements with disappointing results until he found that zirconium and titanium accelerated the polymerization reaction.[2]

Synthesis of Polyethylene

Since Ziegler was working at the Max Planck Institute for Coal Research, ethylene was readily available as a byproduct from coal gas. Because of this cheap feedstock of ethylene and the relevance to the coal industry, Ziegler began experimenting with ethylene, and made it a goal to synthesize polyethylene of high molecular weight. Ziegler was able to obtain high molecular weight polyethylene (MW > 30,000) and, most importantly, to do so at low ethylene pressures. The Ziegler group suddenly had a polymerization procedure for ethylene superior to all existing processes.

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry

In 1952, Ziegler disclosed his catalyst to the Montecatini Company in Italy, for which Giulio Natta was acting as a consultant. Natta denoted this class of catalysts as “Ziegler catalysts” and became extremely interested in their ability and potential to stereoregularly polymerize α-olefins such as propene. Ziegler, meanwhile concentrated mainly on the large-scale production of polyethylene and copolymers of ethylene and propylene. Soon the scientific community was informed of his discovery. Highly crystalline and stereoregular polymers that previously could not be prepared became synthetically feasible. For their work on the controlled polymerization of hydrocarbons through the use of these novel organometallic catalysts, Karl Ziegler and Giulio Natta shared the 1963 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Ziegler retired from the institute in 1969 and became an honorary senator of the institute.[2] As a man of many discoveries, Karl Ziegler was also a man of many patents. As a result of his patent agreement with the Max Planck Institute, Ziegler was a wealthy man. With part of this wealth, he set up the Ziegler Fund with some 40 million deutsche marks to support the institute’s research.

Karl Ziegler died in Mülheim, Germany August 12, 1973, at age 74.

John McGeehan, GREAT lecture: Turning the Tide on Plastic Pollution, [5]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Karl Ziegler biographical, Nobelprize.org

- [2] Karl Ziegler, German chemist, at Britannica Online

- [3] Karl Ziegler and Giulio Natta, at Chemical Heritage Foundation

- [4] Karl Ziegler at Wikidata

- [5] John McGeehan, GREAT lecture: Turning the Tide on Plastic Pollution, britishcouncilsg @ youtube

- [6] Bawn, C. E. H. (1975). “Karl Ziegler 26 November 1898 — 11 August 1973”. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 21: 569–584.

- [7] Eisch, John J. (1983). “Karl Ziegler: Master Advocate for the Unity of Pure and Applied Research”. Journal of Chemical Education. 60 (12): 1009–1014.

- [18] Timeline of Nobel Laureates in Chemistry, via Wikidata