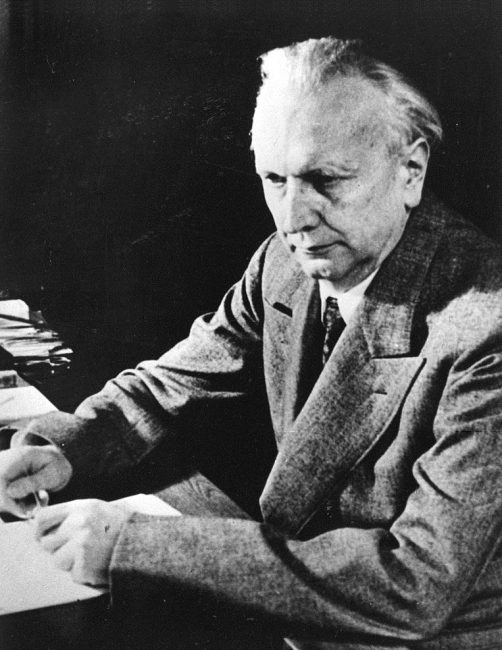

Karl Jaspers (1883 – 1969)

On February 23, 1883, German-Swiss psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers was born. Jaspers had a strong influence on modern theology, psychiatry, and philosophy. He was often viewed as a major exponent of existentialism in Germany.

“Man, if he is to remain man, must advance by way of consciousness. There is no road leading backward. … We can no longer veil reality from ourselves by renouncing self-consciousness without simultaneously excluding ourselves from the historical course of human existence.”

— Karl Jaspers, Man in the Modern Age (1933)

Family Background and Early Years

Karl Jaspers was the son of Carl Wilhelm Jaspers (1850-1940), bank director and Member of the State Parliament, and his wife Henriette née Tantzen (1862-1941). Karl Jaspers was a pupil of the Old High School in Oldenburg. From childhood on, Jaspers suffered from bronchial problems (congenital bronchiectases), which considerably impaired his physical performance and made him susceptible to infections. Jaspers first studied law in Heidelberg at the end of 1901 and later in Munich for three semesters. After a stay at a spa in Sils-Maria, he began studying medicine in Berlin in 1902, which he continued from 1903 in Göttingen and from 1906 in Heidelberg. In 1908, with the support of Karl Wilmanns, he received his doctorate under the supervision of Franz Nissl, the director of the Psychiatric University Hospital, who gave him the opportunity to work as a volunteer assistant after his licensure from 1909 to 1914.

General Psychopathology

Max Weber, whom he had met in 1909, became a scientific role model for Jaspers.[1] In 1910/11 he temporarily participated in the working group on Sigmund Freud‘s psychological theories and related views. Jaspers never mentioned this circle, although he himself later called for a scientific justification of psychotherapy and critically examined psychoanalysis and its ideological claims until the end of his life. On 13 December 1913, at the age of thirty, Jaspers, supported by Nissl and Weber, presented his textbook on General Psychopathology to Wilhelm Windelband at the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Heidelberg as a habilitation thesis and was able to habilitate in psychology. With this book, Jaspers left behind a groundbreaking work when he changed to the philosophy of psychiatry, which immediately found great recognition in the professional world. With his expansion of the psychiatric arsenal of methods to include the psychological-phenomenological method describing the mental symptoms of illness, Jasper overcame the reservations of brain research against what he called brain mythology and at the same time went well beyond Wilhelm Wundts’ experimental-psychological approach to psychiatry, which Emil Kraepelin had introduced before him.[2,3]

World War and Academic Career

During the First World War Karl Jaspers was afraid of being drafted into the Landsturm without a weapon due to his poor health, which he was spared. Already after two years of teaching at the Philosophical Seminar of the University of Heidelberg, Karl Jaspers was appointed extraordinary professor there in 1916. In 1920 he succeeded Hans Driesch and became an associate professor. In the same year his friendship with Martin Heidegger began, which lasted until he joined the NSDAP in May 1933.[6] In 1921, negotiations about his vocations led to the establishment of a personal ordinariate for him and he became co-director of the seminary alongside Heinrich Rickert in 1922. In the following years Jaspers concentrated on an intensive and deep familiarization with the history and systematics of philosophy. At first he read about the great philosophers and in 1927 he began to elaborate his three-volume main work Grundriss der Philosophie. Hannah Arendt received her doctorate in 1926-1928 from Jaspers. Their friendship began in 1932 and only ended with his death.

Karl Jaspers in Nazi Germany

After the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, Jaspers was considered to have a “Jewish taint” (jüdische Versippung, in the jargon of the time) due to his Jewish wife, and was forced to retire from teaching in 1937. In 1938 he fell under a publication ban as well. Many of his long-time friends stood by him, however, and he was able to continue his studies and research without being totally isolated. But he and his wife were under constant threat of removal to a concentration camp until 30 March 1945, when Heidelberg was liberated by American troops.

Postwar Career and Emigration to Switzerland

“The Greek word for philosopher (philosophos) connotes a distinction from sophos. It signifies the lover of wisdom (knowledge) as distinguished from him who considers himself wise in the possession of knowledge. This meaning of the word still endures: the essence of philosophy is not the possession of the truth but the search for truth.”

— Karl Jaspers, Way to Wisdom: An Introduction to Philosophy (1951)

After 1945, Jaspers was one of the most distinguished scientists who contributed to the reestablishment and reopening of the University of Heidelberg. Disappointed by the further development of general and higher education policy in post-war Germany, Karl Jaspers accepted the call to Basel and in 1948 moved to Paul Häberlin’s chair there as his successor. As a reaction to the election of former NSDAP member Kurt Georg Kiesinger as Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany and the passing of the emergency laws in 1968, Jaspers also acquired Swiss citizenship. He continued to make highly regarded statements on issues of the time as well as on scientific topics such as psychoanalysis. Karl Jaspers died in Basel in 1969 at age 86.

Philosophy of Existentialism

Most commentators associate Jaspers with the philosophy of existentialism, in part because he draws largely upon the existentialist roots of Nietzsche and Kierkegaard, and in part because the theme of individual freedom permeates his work.[7] In Philosophy (3 vols, 1932), Jaspers gave his view of the history of philosophy and introduced his major themes. Beginning with modern science and empiricism, Jaspers points out that as we question reality, we confront borders that an empirical (or scientific) method simply cannot transcend. At this point, the individual faces a choice: sink into despair and resignation, or take a leap of faith toward what Jaspers calls Transcendence. In making this leap, individuals confront their own limitless freedom, which Jaspers calls Existenz, and can finally experience authentic existence

Is Philosophy Science?

For Jaspers philosophy was not a science, but rather existential enlightenment, which deals with being as a whole. Every utterance about philosophy is itself philosophy. Philosophy occurs where people wake up. Philosophy is the awareness of one’s own powerlessness and weakness. Jaspers thus distinguished scientific truth from existential truth. While the one is intersubjectively comprehensible, one cannot speak of knowledge with the other, since it is directed towards transcendent objects (God, freedom). Science knows progress, philosophy in his opinion does not. Jaspers was strictly opposed to the mixing of philosophy as he understood it with a philosophy that wanted to compete with science and limited itself to its methods. This makes itself the maid of science.

Karl Jaspers’ work comprises more than 30 books with about 12,000 printed pages and an estate of 35,000 sheets with several thousand letters.

Karl Jaspers – Kleine Schule des philosophischen Denkens. [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Max Weber – one of the Founders of Sociology, SciHi Blog

- [2] Wilhelm Wundt – Father of Experimental Psychology, SciHi Blog

- [3] Emil Kraepelin’s classification system for Mental Illness, SciHi blog

- [4] Karl-Jaspers-Gesellschaft Oldenburg

- [5] Existential Primer: Karl Jaspers

- [6] Martin Heidegger and the Question of Being, SciHi Blog

- [7] God is Dead – The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, SciHi Blog

- [8] Karl Jaspers. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- [9] Jaspers, Karl (1941). “On My Philosophy”

- [10] Karl Jaspers at Wikidata

- [11] Karl Jaspers – Kleine Schule des philosophischen Denkens. Benedikt Schmidt @ youtube

- [12] Timeline of Existentialists, via DBpedia & Wikidata