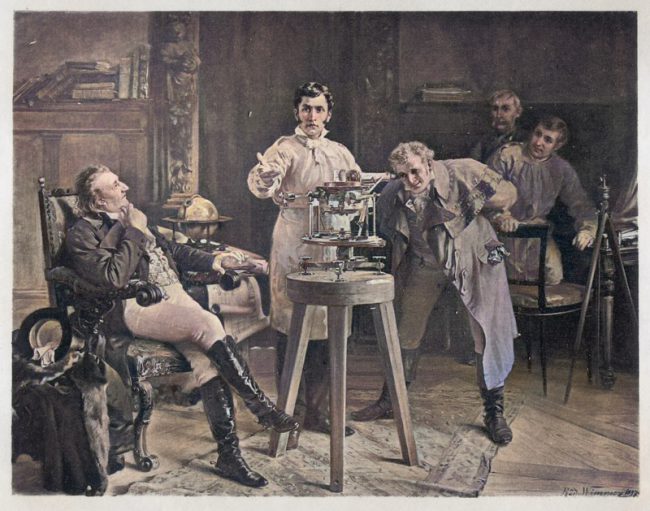

Joseph von Fraunhofer (1778-1826) demonstrating the spectroscope

On March 6, 1787, German optician and physicist Joseph Fraunhofer – later enobled Ritter von Fraunhofer – was born. He is known for the discovery of the dark absorption lines known as Fraunhofer lines in the Sun‘s spectrum, and for making excellent optical glass and achromatic telescope objectives. Moreover, he is the name giver for the German Fraunhofer Society for the advancement of applied research.

“In all my experiments I could, owing to lack of time, pay attention to only those matters which appeared to have a bearing upon practical optics”

— Joseph Fraunhofer, as quoted in [8]

Early Life

Joseph Fraunhofer was born in Straubing, Bavaria to Franz Xaver Fraunhofer and Maria Anna Fröhlich. His father and grandfather were both master artisans of glassmaking. His mother’s side of the family contained a line of glassmakers dating back to the early seventeenth century. He became an orphan at the age of 11, and he started working as an apprentice to a court mirror maker and decorative glass cutter named Philipp Anton Weichelsberger. He spent his first pennies at the flea market on an elementary textbook of geometry which he studied in his spare time. In 1801, the workshop in which he was working collapsed and he was buried in the rubble. Though unhurt, Fraunhofer was trapped beneath the wreckage, prompting a large community rescue operation, which was led by Maximilian IV Joseph, Prince Elector of Bavaria (the future Maximilian I Joseph). The prince was moved by Fraunhofer’s plight, providing him with books and forcing his employer to allow the young Fraunhofer time to study.

Stamp issued for the 200th birthday of Fraunhofer

The Achromatic Lenses of Fraunhofer

In 1804, he became a decorative glass making and cutting journeyman. However, he didn’t like the work and started resenting his master Weichselberger, who would not allow Fraunhofer to study optical theory and tried to prevent him from attending a school for working youths. In 1806 Joseph Utzscheider and Georg von Reichenbach then brought Fraunhofer into their Institute at Benediktbeuern, a secularised Benedictine monastery devoted to glass making, where Fraunhofer discovered how to make the world’s finest optical glass and invented incredibly precise methods for measuring dispersion. Fraunhofer invented a machine which rendered the surface more accurately than traditional grinding. In 1809 the mechanical part of the Optical Institute was chiefly under Fraunhofer’s direction, and that same year he became one of the members of the firm. In 1814, Fraunhofer became a partner in the firm and the name was changed to Utzschneider und Fraunhofer. In this context, the improvement of the achromatic lens pair invented a few years earlier in England is important for astronomy. Instead of putting the two lenses together by cementing them together, Fraunhofer put them in line with an air gap. This resulted in additional degrees of freedom to correct optical aberrations. Corresponding Fraunhofer achromatics are still used today in amateur astronomy. It was during his experiments that Fraunhofer noticed dark lines within the spectrum of the sun. But, we have to begin a little earlier.

The Spectroscope

In 1814, Fraunhofer invented the spectroscope. In the course of his experiments he discovered that bright fixed line which appears in the orange color of the spectrum when it is produced by the light of fire. This line enabled him afterward to determine the absolute power of refraction in different substances. Experiments to ascertain whether the solar spectrum contained the same bright line in the orange as that produced by the light of fire led him to the discovery of dark fixed lines in the solar spectrum. Although a few dark lines had been identified earlier in 1802 by William Hyde Wollaston, Fraunhofer’s precise equipment enabled him to discern 574 individual lines in the spectrum of the sun. He did not concern himself with the theory behind these lines, but he did use them to assist in measuring the refractive index of the glass he was producing. Later, these dark fixed lines were shown to be atomic absorption lines, as explained by Gustav Kirchhoff in 1859.[3] Together with Robert Bunsen Kirchhoff discovered that each chemical element was associated with a specific number and arrangement of spectral lines. They concluded from this that the lines observed by Wollaston and Fraunhofer were due to the absorption properties of these elements in the upper layers of the sun and therefore had to be present in the photosphere. Some of the lines, however, are also caused by the elements of the Earth’s atmosphere. However, in Fraunhofer’s honor these lines are still called Fraunhofer lines.

Stellar Spectroscopy

Fraunhofer used his spectroscope, which he had turned into a precision instrument, to examine the emission spectra of many elements. He discovered that different elements released different lines along the spectrum. He also found that the moon and planets gave the same pattern as the sun, but other stars gave different patterns, thus founding stellar spectroscopy. He worked to locate and identify all the lines by emitted by the sun by measuring their wavelength. While researching spectral lines, Fraunhofer usually used prisms or thin slits to separate light by its component colors. However, he realized that a wire mesh could be employed, acting as multiple thin slits. The principles of this so-called diffraction grating have been discovered by James Gregory [4] and the American astronomer David Rittenhouse [5] invented the first man-made diffraction grating in 1785. Thus, in 1821 Fraunhofer constructed a diffraction grating comprised of 260 wires, producing a widely dispersed spectrum, which as he later found out could produce an even dispersion when the wires were set closer together.

Later Years

In his firm, Fraunhofer produced various optical instruments including microscopes. This included the 24-cm Fraunhofer Dorpat refractor used by astronomer Friedrich Georg Wilhelm Struve at the Pulkovo Observatory in Russia around 1825, and the 16-cm Bessel Heliometer, which were both used to collect data for stellar parallax for the first measurement of the distance between a star (61-Cygni) and the earth. In 1823 he became Professor and full member of the “physikalischen Kabinett” in Munich. Joseph von Fraunhofer passed away in 1826 because of tuberculosis a few months before his 40th birthday. In 1829, after the death of Fraunhofer, a second, identical copy of theFraunhofer Dorpat refractor was given to the Berlin observatory with which Johann Gottfried Galle discovered the Neptune in 1846.[6] The completion of his heliometer for the Königsberg Observatory has also not happened to Fraunhofer.

Andy Masley, Absorption and Emission Spectra – IB Physics, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Colan Kennelly: Joseph von Fraunhofer

- [2] Joseph von Fraunhofer at Britannica.com

- [3] Gustav Kirchhoff and the Fundamentals of Electrical Circuits, March 12, 2014.

- [4] James Gregory and the Gregorian Telescope, SciHi Blog, November 6, 2015.

- [5] David Rittenhouse and the Transit of Venus, SciHi Blog, April 8, 2015.

- [6] Johann Gottfried Galle and Planet Neptune, SciHi Blog, June 9, 2014.

- [7] Joseph von Fraunhofer at Wikidata

- [8] Prismatic and Diffraction Spectra: Memoirs (1899) Tr. & Ed. J. S. Ames p. 10

- [9] Andy Masley, Absorption and Emission Spectra – IB Physics, Andy Masley’s IB Physics Lectures @ youtube

- [10] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 43.

- [11] Howard-Duff, Ian (1987). “Joseph Fraunhofer (1787-1826)”. Journal of the British Astronomical Association. NASA Astrophysics Data System. 97: 339

- [12] Timeline of spectroscopists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #29 | Whewell's Ghost